A Department of Education report on foreign funding at universities sparked a three-year Department of Justice (DOJ) investigation into Stanford that, last fall, culminated in a nearly $2 million settlement deal.

Interviews with lead DOJ investigator Thomas Corcoran, faculty members and University officials unpacked the investigation into the University’s alleged failure to disclose foreign support from countries such as Australia, China, Israel and Japan in federal research grant proposals.

The settlement came amid government officials’ growing unease over foreign influence in federal research, particularly from China. On the opposing side, academics and civil rights organizations have argued that strict federal rules inhibit academic freedom and international cooperation.

Several professors criticized the University in October for its decision to settle, telling The Daily it created a wrongful appearance of misconduct and could unfairly damage their reputations. Others expressed confusion.

“Stanford continuously updates our policies and designs systems to support disclosure by research personnel on sponsored research grants,” wrote University spokesperson Dee Mostofi to The Daily. “We and other research universities strive to be good partners with federal agencies to comply with evolving federal rules and practices, and to respond to any concern when it is raised.”

In recent months, University officials have launched several initiatives aimed at strengthening compliance with government rules while protecting academic freedom.

Inside the DOJ investigation

A 2020 report from the Department of Education triggered the three-year investigation into Stanford. The Department of Education raised concerns that Stanford and other universities had fallen short of requirements to report foreign contracts and gifts over $250,000 under Section 117 of the Higher Education Act.

In response, Corcoran, an assistant United States attorney who co-led the investigation, said the DOJ issued a subpoena to Stanford in 2020 requesting information about gifts, funding and research support from foreign sources between 2015 and 2020. The DOJ then cross-referenced this information with federal research awards to the University.

“That’s where we found the problems,” Corcoran said, alleging that Stanford’s failure to disclose additional “current or pending foreign support” for research violated federal requirements.

Corcoran declined to name other universities where the DOJ identified similar failures. “There are others. Let’s just leave it at that,” he said.

Referring to grants awarded to Richard Zare, the Marguerite Blake Wilbur Professor of Natural Science, Corcoran alleged the concealment of foreign funding that made Zare “overcommitted.” He said this problem went beyond the other professors’ alleged disclosure failures because Zare had dedicated more time than was allowed to different projects.

Zare did not respond to a request for comment.

“[Zare’s case] was different,” said Corcoran. “He didn’t tell the truth to the federal agencies that he was already [over]committed on everything else that he was doing, so he had no time to do work on the federal awards.”

Corcoran highlighted Zare’s affiliation with the National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC) and Fudan University, saying he failed to disclose ties to both institutions on grant proposals. Corcoran also claimed that Zare omitted support from entities in other countries, including Israel, Japan and Australia.

For Corcoran, Zare’s alleged omissions were compelling. He described speaking with another researcher at a different university who lost out on the NSF funding that Zare received.

“He was very upset,” Corcoran said. “If you play by the rules and you lose it, [while] someone doesn’t play by the rules and they get it, that bothers me.” Corcoran declined to share the researcher’s identity.

Nonetheless, the DOJ brought its claims against the University rather than individuals. Corcoran stressed that his goal was for universities to “clean up,” not to punish professors for errors. The agreement between Stanford and the DOJ made no determination of liability.

“The case was about the failures of the university, the Office of Sponsored Research, to have systems in place to make sure they were catching everything that these professors were doing time-wise and support-wise, and to make sure that it was properly disclosed,” he said.

The negotiating table

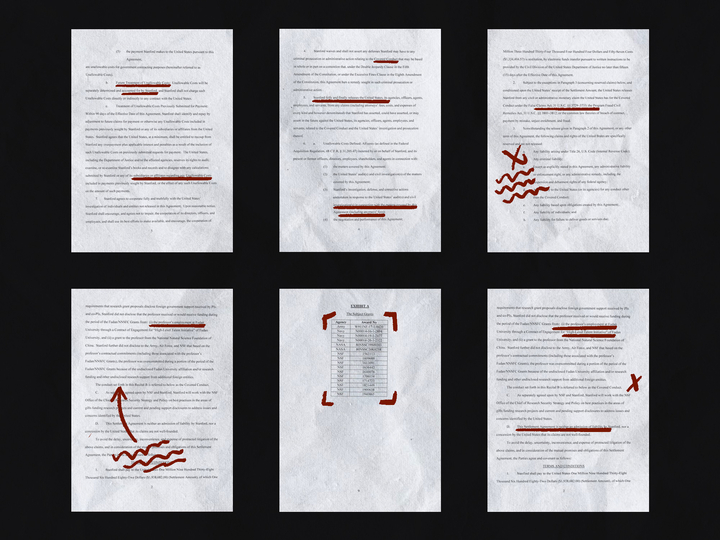

In conversations with the DOJ, the University successfully argued that many federal grant proposals in question complied with government rules, Corcoran said. This narrowed the DOJ’s case down to 23 grants that assisted 12 professors.

The University claimed that it was unaware of reporting requirements for industry funding, Corcoran said. Faculty members echoed this point, including one professor who shared a communication in which a manager at a Stanford research office suggested that the office did not consider it a requirement to disclose industry gifts at the time.

In Corcoran’s view, however, federal regulations were unambiguous. He added that the DOJ took issue with such gifts because they “had very detailed research components” attached to them, potentially overcommitting professors’ time at the expense of federal research.

In response to the allegations, the University pursued a settlement rather than attempt to defend itself in court. Kam Moler, who served as Vice Provost and Dean of Research at the time, wrote to The Daily that this decision best supported research.

Moler wrote that she and others recommended the settlement to the president and provost. “I supported settling because it was the best path to move forward on all of the federally funded research being done by the professors and their students,” Moler wrote.

Moler also wrote that she participated in one meeting with the DOJ about the settlement.

Although the federal awards that Stanford professors received totaled far more, the agreed-upon figure of $1.9 million represented $1.3 million of Stanford professors’ time, salary, fringe and indirect costs that were charged to the award, plus a $600,000 penalty. The parties signed the settlement on Sep. 28 and 29.

The fallout

Stanford’s settlement with the DOJ attracted national attention, creating waves on campus among faculty members concerned about reputational damage. Many professors involved in the case were surprised to see the press release publicly list their specific grant numbers. Some said the University had told them the grant numbers would be kept private.

Mostofi wrote that “Stanford was not informed of and had no control over the DOJ’s decision to disclose the individual award numbers as part of the government’s press release.”

Corcoran disputed this.

“The lawyer for the University definitely knew those awards, by number, were going to be attachments,” he said. “Whether that trickled down to the University, and whether that trickled down to the actual professors, I don’t know the answer.”

The University did not respond to a question about the accuracy of Corcoran’s statement.

Corcoran said it was necessary to publicize the specific grant numbers to narrowly define the claims being released by the settlement, compared with thousands that “could still be subject to scrutiny,” he said.

Corcoran added that the DOJ did not intend to identify specific professors. “I didn’t realize people could Google it and figure it out pretty quickly,” he said.

Corcoran dismissed professors’ concerns that the settlement created a false appearance of misconduct, saying “I don’t know if I feel that badly for them.”

He said he thought Stanford professors would still apply for both foreign and federal awards, and likely still receive them. “If they really are as smart as they think they are … they’ll continue to get awards,” he said. “Aren’t these the brightest people in the world?”

China and foreign influence fears

In recent years, Congress and federal departments have taken a vigorous approach to combating foreign influence in academic research. In 2018, the DOJ launched the China Initiative, a law enforcement effort that focused on prosecuting espionage carried out by alleged Chinese agents at U.S. universities. Critics argued that the initiative undermined research and promoted racial bias against Asian American academics.

The DOJ shut down the China Initiative in 2022.

Although she did not comment specifically on the settlement, chemical engineering professor Zhenan Bao told The Daily that in the current landscape, “there’s no doubt Chinese Americans are being more targeted, and more Chinese researchers in the U.S. have been charged, also wrongly charged.”

Bao said she follows the rules to the best of her ability, but the government’s policies created anxiety: “I feel ‘what if I missed something?’ Then would I be put in jail or something? It’s not a good feeling to have.”

Two physics professors, Steven Kivelson and Peter Michelson, echoed Bao’s criticism of government policies, including the China Initiative.

Kivelson refrained from labeling the Stanford-DOJ settlement as an example of racial profiling, saying he did not have enough information to comment. “There’s a huge research enterprise” in China, he said. “I don’t want to draw a line from that to racial profiling.”

Corcoran stressed that his investigation “had nothing to do with” the China Initiative and did not represent a continuation of the DOJ’s strategy. In a departure from the China Initiative, the DOJ took a civil rather than criminal approach to the case, bringing its charges under the False Claims Act.

When asked whether he believed Asian American academics had reason to fear legal action from the government, Corcoran said, “I am just a civil attorney here at the DOJ in the District of Maryland.”

“Nobody has anything to fear from me with regard to targeting Asians at all. None whatsoever,” he added.

Corocoran added that exclusively naming Chinese affiliations in the settlement announcement was not political, and that researchers also had affiliations with other countries. “I probably should have named the countries just to make sure everybody was aware,” he said. “I’d never even thought about it.”

Bao said that while Stanford’s research offices were “trying very hard” to support faculty with grant applications, rapidly changing federal rules made this more challenging. “The biggest concern I have is, the policy itself is not very clear,” she said.

Kivelson said he had no background knowledge on the settlement, but expressed disappointment in the University’s decision. “If there was actual malfeasance, then someone should do something about that,” he said. “But if not, I would have preferred that Stanford would have contested it.”

The three professors shared concerns that government policies could have a chilling effect on international cooperation, with significant costs to innovation. According to Bao, researchers at other universities have faced penalties or professional consequences when collaborating with foreign countries. Speaking personally, Bao said she now had to gain approval from federal agencies to deliver research talks in China, even online.

Kivelson described government restrictions on international cooperation as “self-destructive.” He said that scientific research disproportionately relied on foreign nationals and, increasingly, exchange with China. “If we cut off exchange with China, we cut off access to all of this knowledge,” he said.

Michelson worried that government policies could erode the University’s research principles of openness and nondiscrimination. “The suspicion around students of Chinese origin does not create an inclusive community,” he said.

Amid growing tensions between China and the U.S., Kivelson added that informal communication between scientists could be vital, drawing a comparison to the Cold War. “A lot of people think they are defending this country trying to cut off China, and I think they’re selling our country short.”