Sarah Ida Raphaelle Muller lived a life of music and dance, before she passed away on Feb. 19 in a fatal bike collision at the age of 28.

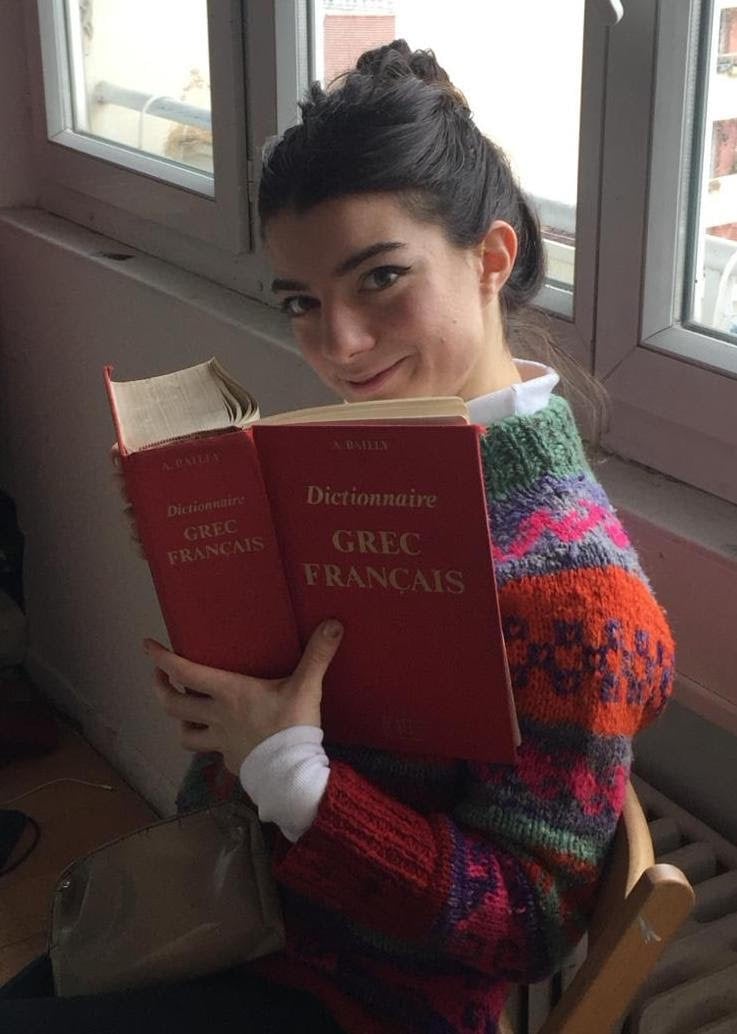

Muller arrived at Stanford in January with a fellowship from the France-Stanford Center for Interdisciplinary Studies and intended to conduct research for her Ph.D. dissertation on the “Representation of Dance Performances in Greek Poetry, from Homer to the fifth century BCE.”

Classics professor Anastasia-Erasmia Peponi, Muller’s faculty mentor, wrote in a statement to The Daily that Muller’s “large smile and her expressive eyes filled our rooms.”

Sinead Brennan-McMahon, a fifth-year Ph.D. student in classics and digital humanities, wrote that Muller had been extremely full of life. Brennan-McMahon recounted times when she and Muller would discuss job prospects, joking about “whether legally changing your name to “Et Al” would improve your publishing record and chances of landing a job.”

Angélique Lemarchand, another visiting researcher with the France-Stanford Center for Interdisciplinary Studies, met Muller earlier this year on campus before the two became fast friends.

“Sarah was bright with her whole being. Brilliant and modest, deeply kind, and full of life,” Lemarchand wrote.

A trained dancer and accomplished piano player, Muller’s academic interests were highly influenced by the activities in her life that brought her joy. In her scholarship, she studied the music and dances of the Greek gods in early poetry. She wanted to focus on the divine choreography and its importance in understanding conceptualizations of divine dance in Greek poetry.

Friends and colleagues say Muller’s passion in dance and music lived deep inside her, inseparable from her academic interests.

Muller received her first degree at Sorbonne University in Paris, with a specialization in Ancient Culture and the Contemporary World. She later moved to the University of Nanterre to work with Nadine Le Meur-Weissman, a professor of Greek and Latin languages and literature, who supervised her masters thesis, which she completed in 2020, and her Ph.D. thesis, which she was in her third year of working on.

In October 2022, Peponi and Muller first met at a conference at Nanterre.

“Although our conversation was quite brief then, it was clear to me that she was exceptionally knowledgeable and very passionate about the subject of her thesis,” Peponi wrote.

When Muller arrived at Stanford, Peponi invited Muller to sit in at her graduate seminar whenever she wanted to take a break from researching for her dissertation work. The seminar topic, Greek Philosophy on Poetry and the Arts, was not directly relevant to the research Muller was conducting, but she was still enthusiastic and joined the very first class, never missing a class after that.

Sitting in on the seminar allowed Muller to meet and connect with Stanford students like Enver Ali Akoba, a first-year Ph.D. student in comparative literature.

“My brief memory of Sarah, of her insightful and humble comments in the classroom, and our engaging, mindful conversations after classes, inspire the ideal of a true intellectual,” Akoba wrote.

Sasha Barish, a first-year Ph.D. student in classics and another student in the seminar, said that Muller was very warm and conversational in the seminar. While Muller observed most of the seminar, whenever she did speak, her contributions were often intellectual and thoughtful, and it was clear that the topic was something she was interested in.

Before Muller’s passing, she gave Peponi parts of her dissertation to read.

“Sarah figured out more clearly and more creatively than anybody else the choreographic schemes inherent in the descriptions of the dances of the gods in early Greek poetry,” Peponi wrote.

According to Peponi, current scholarship focused on the discovery of orderly geometric shapes in dances and choreographies. However, Muller’s reading of the texts demonstrates there’s more harmony in what seemed to be a disordered choreography that allowed various shapes and forms to take place at the same time. Peponi described the parts of the dissertation that she read as potentially pathbreaking.

“Her scholarship, her dancing, her music, were all harmoniously living inside her and nourishing one another. She was quietly making a poem of herself,” Peponi wrote.