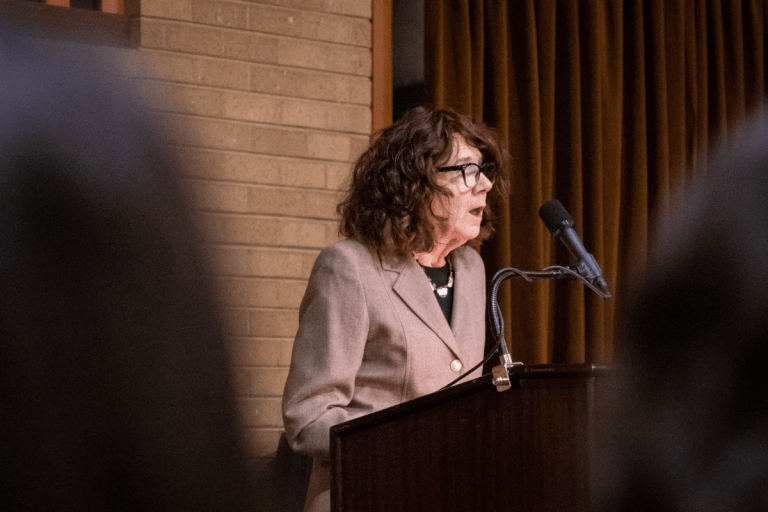

“Welcome to poetry,” Mary Ruefle read from her poem “The Bark” on Wednesday night at Stanford Faculty Club. The line captured the moment when the speaker’s dog, who continued to bark at its own echo across a lake, thought another dog was barking at it.

The Stanford community was treated to the Lane Lecture Series reading from Ruefle, a darkly funny and down-to-earth writer. Her most recent poetry collection, “Dunce,” was a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize in poetry.

The Vermont-based poet and prose author has also been highly praised as an erasure artist, whose erasures from various nineteenth-century texts have been widely celebrated. Her creations have been displayed at museums and galleries.

The highlights of the night included Ruefle’s introduction by the Nobel Prize-winning poet and Stanford Professor Louise Glück.

“One of the great American regionals, Mary Ruefle writes as a spirit newly hatched, without existing convictions or prejudices,” Glück said.

Ruefle’s reading was fused with prose and poems, from her new work “Dunce” and her older collections. Setting the night’s theme of snowy weather, which has recently hit California, her first poem “Snow” explored the moments and emotions created by these snow days.

“Everytime it starts to snow, I would like to have sex.” read Ruefle. This humble and blunt humor set the tone for the rest of the poem, as well as the rest of the evening.

“I would like to be in the classroom — for I am / a teacher — and closing my book stand up, saying / ‘It is snowing and I must go have sex, good-bye,’ and walk out of the room,” she continued. The audience giggled. The poem then transitioned to a deeper reflection of quiet seclusion found in this type of winter weather.

To conclude her reading, Ruefle shared a marvelous typewritten letter that she didn’t write but wished she did. She couldn’t remember where she found the letter but explained it had probably been rediscovered by herself in one of her many folders. Ruefle estimated that the lighthearted letter, addressed from Lawrence to a friend called Ruth, was dated around the 1920-40s.

In the second part of the night, Ruefle answered various questions from the audience and shared her writing secrets.

“My first book of prose is among my favorites,” reflected Ruefle, referring to her prose book “The Most of It.”

When asked what her writing process was, Ruefle said matter-of-factly, “I don’t write every day.” She went on to explain that she doesn’t have a formal process. “A loop of sound gets into my head, and it won’t stop and it’s like a worm. It just keeps looping. It has a rhythm, and words come out,” she told the audience.

She explained that if she gets lucky the whole poem comes to her, but it rarely happens. A poem usually starts with a line or an image. “The ideas don’t start ever on lined paper. They start in my head,” said Ruefle.

Most of Ruefle’s poems are based around experiences she has in her everyday life. Her poetry centers around ordinary objects and events, such as yellow tulips or driving to the dump, but always draws back to greater truths found in life and death.

One poem that she read, titled “The Wild Rose Bush,” begins by depicting the simple chore of pruning the wild rose bush, and why she could not bring herself to do the chore. Ruefle expands on this point, citing the long life the wild rose bush must have lived in its “sixty years of childhood.”

The wild rose bush, an experienced creature, is then developed into a metaphor for her own father, who “never did anything of interest.” She describes how he must have realized that the world would keep moving forward without him, even after he dies. Ruefle ends the poem with a comparison of the way her father looked after he died (“his head lolled to one side”) to a dead rose.

“It’s all writing, it’s all literature, it’s all a chosen waste of time,” Ruefle said cleverly about her reading, eliciting laughter from the captivated audience.

Editor’s Note: This article is a review and includes subjective thoughts, opinions and critiques.