What is art if not the amalgamation of cultural experience, trauma and nostalgia?

On Tuesday evening, the Cantor Arts Center sponsored the webinar discussion “Beyond the Camps: Art, Experience, and Executive Order” to examine questions like this. The Bay Area artists and collectors Masako Takahashi and Patrick Hayashi engaged in a passionate conversation about creative expression, memories of Japanese American incarceration during World War II and the future of Asian American art.

Takahashi and Hayashi shared their personal experiences relevant to the Japanese American identity displayed in the artworks shown to the audience. Hayashi is an Oakland-based artist who started collecting art related to Japanese American incarceration around 30 years ago. He gifted a piece to the “After Executive Order 9066” collection to the Cantor, which references the forced evacuation of more than 120,000 Japanese Americans to isolated detention centers and concentration camps during World War II.

Takahashi, born in Topaz Concentration Camp, Utah, contributed the piece “Friendship Series/Cardinal Points” consisting of her own embroidered hair. The length of the words corresponds to the length of each individual hair. “I sort of created my own language,” Takahashi explained. A lot of Takahashi’s work consists of using hair to embroider patterns, putting a creative spin on traditional stitching.

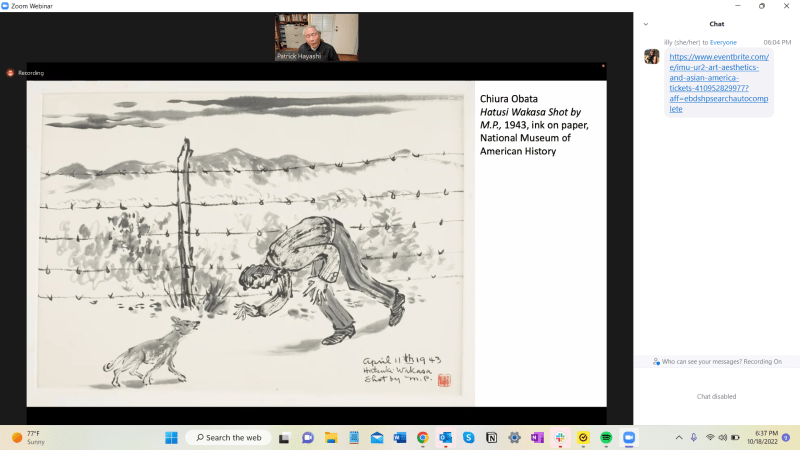

The artwork “Hatusi Wakasa Shot by M.P” stirred the most emotional response from the two artists. Created by Chiura Abata, the ink-on-paper piece displayed an Asian man hunched over in pain after being shot in front of a barbed wire fence with his dog beside him. Hayashi recounted his mother telling him the same story when he was 7 years old and expressed that it was difficult for him to process at the time.

Hayashi further expressed that such artworks relating to the memory of Japanese American internment often evoked strong emotions in him. “I didn’t feel comfortable in a museum,” Hayashi admitted. The first time he entered a museum and came across Obata’s piece, “I just started to sob,” he said.

Takahashi commented on the power of art to cure her trauma. “I never felt comfortable or accepted in the Japanese American community or the public school system,” claimed Takahashi. It wasn’t until she began attending the San Francisco Art Institute that she felt like she belonged. “It’s okay not to be like anyone else,” she realized.

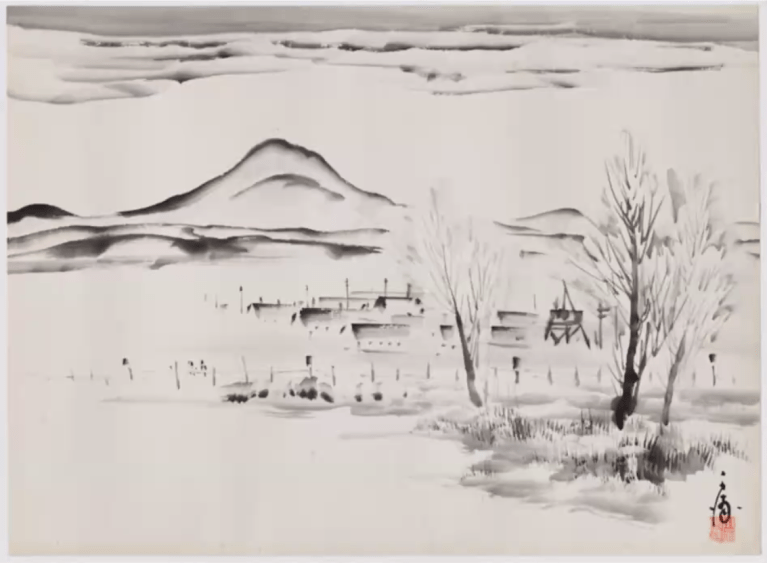

The first piece of the discussion, a gift from Hayashi and his wife, was “Untitled (Topaz),” an ink drawing of the Topaz concentration camp by Chiura Obata. The drawing was juxtaposed with a black-and-white photograph depicting Hayashi and his older brother as toddlers in the camps. The delicate, watercolor-like strokes make the piece seem ironically tranquil for the depiction of a concentration camp.

“This is a tough photograph for me to look at,” Hayashi said. He talked about how such artworks evoke memories of his mother having a rheumatic heart that later turned fatal and his father struggling to keep the family afloat, his personal experience of the intergenerational trauma of Japanese Americans.

“Rage” was a recurring topic in conversations; both artists talked about how it colored their experiences and informed their artistic work. Takahashi admitted that she didn’t know she had anger problems until recently and that it was “a subject I had tried to push away.” She fled to Japan, then went on to travel across the world during her two-year break from university because she felt like she didn’t belong at school or in her community.

The webinar kept the audience engaged with vulnerable conversations and personal anecdotes from the artists. It highlighted crucial aspects of the unique struggles and historical trauma of artists of color, navigating the world’s inequalities using art as a coping mechanism.

Editor’s Note: This article is a review and includes subjective thoughts, opinions and critiques.