The greatest enemy of anyone below 25 is the prefrontal cortex.

Indeed, it is the devil on your shoulder that whispers in your ear, telling you to smoke that weed the night before your economics midterm, resulting in your getting so astronomically high that you can’t even remember what expansionary monetary policy is. It is the gut feeling that, hmm, maybe you should use the rest of your savings to buy those BTS concert tickets! Or the anger in your throat that vomits out those urgent, painful words towards your father, the ones you can’t take back, no matter how much you wish you could.

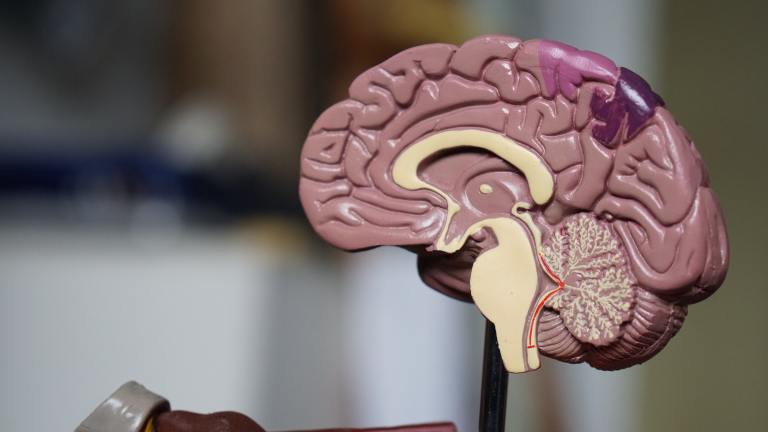

The prefrontal cortex is the cerebral cortex that covers the front section of the brain. This particular region is known for planning complex cognitive behavior, personality expression, decision making and moderating social behavior. Most importantly, it administers the executive function: the coordination of several neural processes in order to accomplish a goal.

Executive function relates to the ability to determine good and bad, same and different, the future consequences of present behavior, prediction of outcomes and what we might consider “social control.” It’s the ability to suppress urges that could possibly be deemed socially unacceptable. The prefrontal cortex invokes concrete learning, or reasoning that heavily relies on observation. At a young age, children think concretely but, with time, transform into abstract thinkers when the prefrontal cortex develops.

Abstract thinking is considered a type of high-order reasoning. It involves the ability to reason beyond that which is directly in front of us. It’s not tied to concrete experiences, people, objects, or circumstances. In order to think abstractly, we must ponder principles that are often symbolic or hypothetical.

But abstract thinking takes time and practice. So I’ve been told. And so I’ve experienced.

In the midst of a heated argument, I once told my father — who, bar none, has an affinity for the highly endangered California Condors — my future plans for a uniquely cruel retribution. I proclaimed that if he were to develop a poor memory in his old age, everyday I would tell him that the endangered scavengers are now extinct — even if they weren’t — so that he would be forced to constantly relive his worst fear in a nightmarish haze.

In the moment I was cruel and insensitive, playing to my father’s weaknesses. Later that day, after the fire in my eyes had been extinguished and my brain defogged, I genuinely apologized, having seen the malice and lack of consideration in my ways. I wasn’t thinking.

Yeah. That was my undeveloped prefrontal cortex.

At least, that’s what my dad said after we made amends. Ironically, he was the one who first taught me about this cerebral phenomenon in a lighthearted moment of education, as he often liked to name the stars and explain the difference between nocturnal and diurnal animals. (Diurnal is the opposite of nocturnal.)

And still, my brain undertook an illicit affair with my mouth and decided to spout vitriol.

According to the National Library of Medicine, the prime time for prefrontal cortex development is during adolescence, and that particularly shifty part of the brain doesn’t fully develop until the age of 25.

Great. When I learned this I thought: how many more years of this nonsense must I endure? When will my filter develop and when will I make better decisions? When will I stop upsetting others (and myself) with my words and actions? When will I learn to think?!

Well, it has been years since I first learned about the prefrontal cortex, and every now and then I still have my California Condor moments. But for the most part, my decision making abilities and filter have developed quite nicely.

What adults don’t tell you is that the best growth is silent. Nobody sees when you break and are forced to pick up the pieces from mistakes with your own bloody hands. Nobody hears the words that make it only as far as the tip of your tongue. Nobody feels the weight of the universe on your shoulders and the fire in your throat as you attempt to navigate a world that was not built for people like you.

Some people are forced to abandon their childhood and grow up too soon, others cling eternally to their youth. But if a developed prefrontal cortex is good for anything — besides incredibly complex and important cognitive functions — it’s maturity.

One cannot simply become an abstract thinker, one who considers concepts beyond what is in front of them, without making mistakes and being a little reckless. If anything, recklessness and mistakes are functions of adolescence and contribute to the grander journey of growth and maturation.

We will all have California Condor moments of our own, but what matters is that we learn from our missteps and take accountability for our actions, especially when they are to the detriment of others and those we love.

For the time being, blame it on the prefrontal cortex! But be warned, that excuse expires the second you turn 25.