“Terror is a given of the place,” concluded acclaimed writer Joan Didion after spending only two weeks in El Salvador in 1982. Salvadoran-American author Roberto Lovato repurposes Didion’s statement in his 2020 memoir, “Unforgetting: A Memoir of Family, Migration, Gangs and Revolution in the Americas,” writing that “terror is a given of the place, but so is love.” Similar expressions tinged with equal grief and gratitude appear throughout Lovato’s “Unforgetting.”

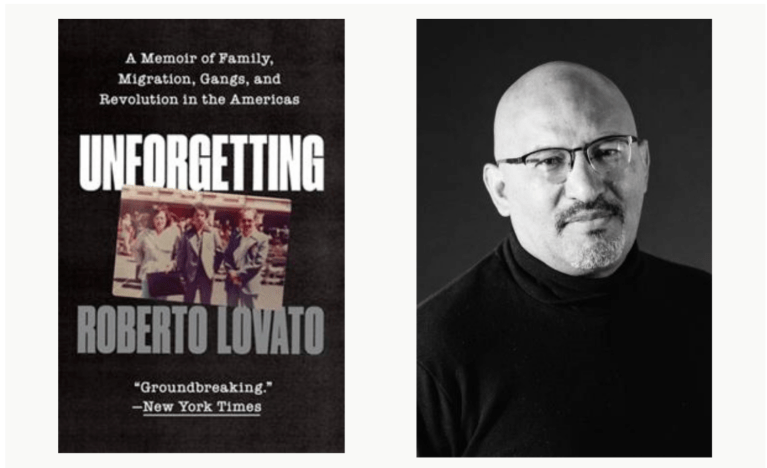

The “groundbreaking memoir” has been lauded as a “kaleidoscopic montage that is at once a family saga, a coming-of-age story and a meditation on the vicissitudes of history, community and, most of all for [Lovato], identity,” according to a rave review from The New York Times, which also named the memoir an “Editor’s Pick.”

On Jan. 14, the Stanford initiative Concerning Violence hosted Lovato for a virtual workshop, entitled “Re-membering the Bones of Personal and Political Violence Across the American Continent.” The event was supported by the Center for Latin American Studies (CLAS) and the Center for Comparative Studies in Race and Ethnicity (CCSRE) and is the first of Concerning Violence’s workshops this quarter.

Future workshops will be organized around the initiative’s 2021-22 theme “Afterlives of Violence: Coloniality and Racial Capitalism in Global Perspective.” Graduate students Noor Amr, Jameelah Morris and Ruben Diaz Vasquez led the workshop, giving attendees a detailed look into the subjects that have inspired Lovato’s memoir. Lovato delivered a dynamic reading, after which sixth-year modern thought and literature Ph.D. candidate Cynthia García offered a response.

Lovato explained, “The memoir is basically a journalist’s search to make his parent’s homeland, El Salvador, ‘the most violent country on earth,’ in 2015, an exploration of what turns children into violent actors and even killers in war and gang violence. Though the deeper story is not about the violence. Violence is just the dark velvet background of the real story, which is the tenderness that survives the terror, the rubies of power.”

Lovato is the Co-Founder of #DignidadLiteraria, a movement that advocates for equity and literary justice “for the more than 60 million Latinx persons left off of bookshelves in the United States.” Lovato has reported on numerous issues including the drug war, violence and terrorism in Mexico, Venezuela, El Salvador, Nicaragua, Dominican Republic, Haiti, France and the United States. He is also the recipient of a reporting grant from the Pulitzer Center.

During the workshop, Lovato discussed the war that ravaged El Salvador in the 1980 and 1990s. He specifically remarked on his difficult decision to join the Farabundo Martí National Liberation Front (Frente Farabundo Martí para la Liberación Nacional, or FMLN). FMLN was an insurgent group turned legal left-wing political party that fought against the U.S.-backed fascist military dictatorship and was responsible for murdering more than 75,000 civilians in El Salvador.

Lovato chooses to follow the tradition of “memoria histórica,” a form of collective memory influenced by shared culture and experience, as he remembers events like these. In the pursuit of justice and deeper truth, Lovato said that the United States planted seeds of violence in El Salvador. He hopes his writing will change the dehumanized and violent mainstream depictions of Salvadorans and help eliminate what he calls “fascist forgetting.”

Throughout his memoir, Lovato also tries to pay homage to the historic poet-warrior tradition of the Americas. In this tradition, the term “warrior” is extended beyond the material military component and manifests in the fight for social justice. He hopes that his own poet “warriorship,” manifest in his memoir, can counteract the forces that have tried to make young Salvadorans “a generation that is amnesiac.”

“That amnesia is neoliberalism and neofacism. For these things to continue in their current forms they need heavy doses of amnesia to be dropped on the population so that young people don’t know the revolutionary struggles of their predecessors,” Lovato said.

This tradition, he said, is the holy water of Salvadoran cultural history and memory that must be drawn from as the world tackles issues of climate change, neoliberalism, neofascism and other colossal challenges. Lovato maintains that “we are not going to ‘progressive liberal’ our way out of them.”

The three main symbols Lovato said he uses to communicate his themes of memory and unforgetting are the machete of memory, the forensic sciences and a sewing machine. The machete, which Lovato says sits on a mantel in every Salvadoran house, is a visceral manifestation of the misconceptions of Salvadoran culture. The machete is inherently nonviolent, a symbol of strength and a source of pride in many households, but destruction, violence and cultural fragmentation ensue when its origins are forgotten and swept over. The forensic sciences stand as the tool that returns bodies to their families. Finally, the sewing machine heals and closes the wounds inflicted by the war.

Despite his aptitude for nonfiction writing, Lovato voiced that he never set out to write a memoir. There were three things he wished to understand: what made El Salvador one of the most violent countries on Earth in terms of homicide, why was he involved in virulent groups as a young person and what he calls his father’s “heavy ass” secret.

“I never intended to write a memoir, then I realized I have my own story that I never told, my own experiences of violence being in a clique here in San Francisco’s Mission District,” Lovato said. “Unforgetting” touches on his experiences in both El Salvador and in the Bay area.

Lovato gave some insight into this father, who was a central figure in the underground world of contraband in San Francisco. This world of trafficking is just one of many that Lovato wanted to bring to light in his writing. In “Unforgetting,” the underworlds of Salvadoran death squads, gang activity, undocumented immigration and Salvadoran-American life are all complexly intertwined. His interest in underworlds stems from the connections he sees between the intimate and the epic.

In the response portion of the workshop, García pointed out the duality of “Unforgetting,” as it “straddles the line between literary and realist,” of “creation and destruction.” García also touched on one of Lovato’s literary choices: tracing early Salvadoran immigration to the United States back as early as the Gold Rush, instead of after the conclusion of World War II. This illumination, García said, was an intervention skillfully made by Lovato that teaches the reader some commonly misunderstood Salvadoran history.

“We live in a moment of extreme terror. But like frogs in a boiling pot, we don’t know the water is boiling,” Lovato said. He designated this “boiling water” as “the neoliberal economic model that drives both climate change and neo-facism, and other extreme and unique components of this very intense moment,” Lovato said.

Lovato’s commitment to unforgetting and his memoir itself are active steps he’s taken to help reverse the systematic erasure of Salvadorans and Latinx people in the United States. In “Unforgetting,” the love of words survives the war.

“I hope the other attendees appreciated Lovato’s message that extreme acts of violence are often fueled by historical amnesia and unforgetting is a powerful tool for seeking truth and reconciliation,” García said. “Unforgetting is also an act of love and the deepest expression of hope.”