After testing positive for COVID-19, Elyse Lowet ’24 packed her bags, preparing to check into isolation housing. In the days that followed, Lowet and other COVID-19-positive students were forced to handle hours-long wait times, academic disruption and unclear instructions as they navigated fast-changing University isolation protocols.

Experiences like Lowet’s have become the norm for COVID-19-positive students amid soaring on-campus case counts, according to the half-dozen isolated students who spoke with The Daily. From broken apartment keys to spoiled food and remote classes on the sidewalk, Stanford’s isolation policies have put student resilience to the test.

Just before Lowet went into isolation on Jan. 5, the University’s demand for isolation housing exceeded its on-campus capacity of 250, said Associate Vice Provost for Environmental Health and Safety Russell Furr. Days later, the University announced that once off-campus housing also runs out, students may have to isolate in their dorms. The plan also included provisions to convert some community bathrooms to “isolation bathrooms,” which has already begun across campus.

When Stanford ran out of isolation housing on campus, they turned to off-campus options, housing students in apartments around Palo Alto. University officials have been trying to find new off-campus spaces every day, Furr said. During this scramble for housing, many students have felt “left in the dark,” said Sam Benabou ’25, who entered isolation on Jan. 3.

“While we were waiting, I had no idea where I would be, what the protocol was or how long I would stay there,” Benabou said. “There wasn’t really any clear direction on what the situation would look like.”

Lowet had to wait two and a half hours before she was sent to Stanford Villa Apartment Homes to begin her isolation. John Kohler ‘22 M.S. ‘23 waited nearly double the time Lowet did.

“It seemed like they were just in a very chaotic, scrambled state,” Kohler said. “They didn’t know who they were going to send where.”

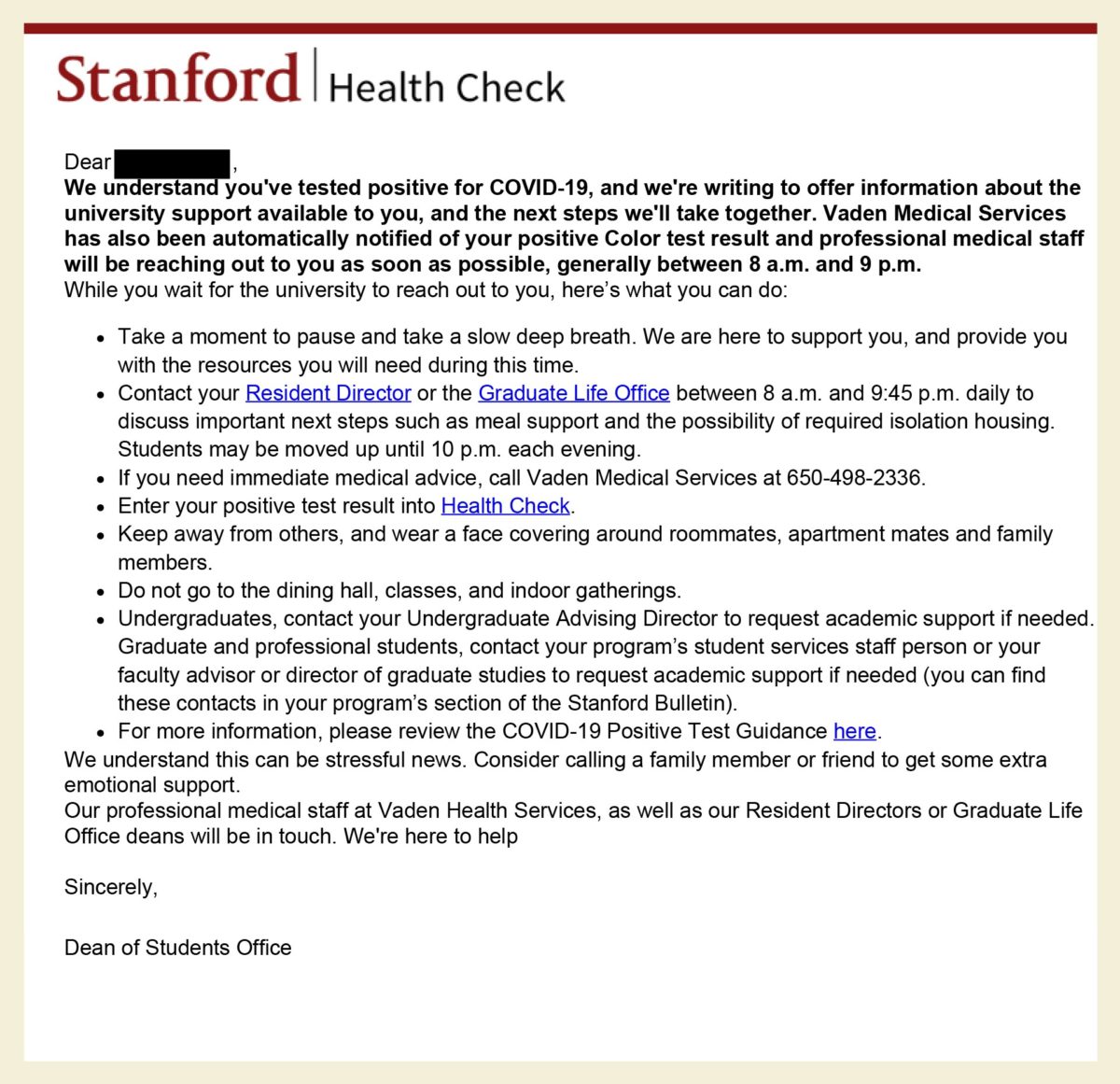

The primary communication that students received after testing positive was an email from the Dean of Students Office instructing students to contact their resident director or the Graduate Life Office while waiting for the University to reach out. But multiple students reported that it took days for them to receive follow-up instructions, and that their calls went unanswered.

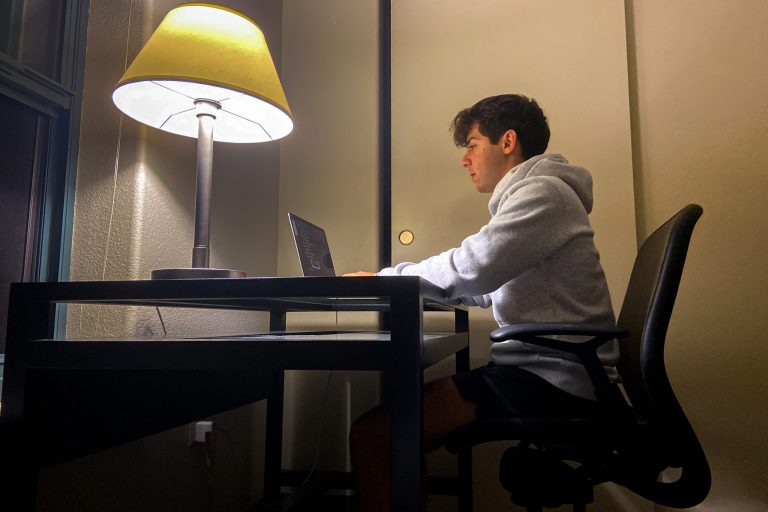

During the wait, students attended online classes from the sidewalk outside of the isolation check-in office. One student propped up his iPad, entered his class Zoom and began practicing social dance in front of an impromptu parking lot audience, according to Kohler.

Staff eventually found housing for the students, who were driven in pairs to their off-campus isolation rooms in what they called the “COVID-19 transport vehicle.” While Kohler’s transport partner got to ride in the van’s proper seat, Kohler said that he rode in a wheelchair strapped to the floor of the van with no seatbelt.

University spokesperson EJ Miranda wrote in a statement to The Daily that the COVID-19 surge on campus “has presented extraordinary logistical challenges at Stanford.” Miranda recommended that students struggling with the isolation process visit this resource for guidance. He did not address the students’ specific experiences.

“University staff have been working diligently around the clock to protect student safety and support the health, academic and emotional needs of students who must isolate,” Miranda wrote. “They are responding in real time to a rapidly evolving situation. We are grateful for the patience and understanding of our students who are dealing with unfamiliar and extraordinary circumstances.”

Upon arrival, some students isolating off-campus were greeted with upscale Menlo Park apartments. Others were unable to get inside.

“When I got there, I stuck my key in the door and the first thing that happened was it instantly broke in the door,” said Max Shen ’25.

Since making his way into the apartment, Shen said he has received “pretty much no communication from anyone.” Lowet echoed Shen’s experience, reporting that it took the University nearly a week to let her know when she was allowed to leave.

For students like Joey McCoy ’25, who was allowed to isolate in Escondido Village Graduate Residences, feelings of disconnect extended into his social life.

“The experience hasn’t been horrible, just lonely,” McCoy wrote in an email. “During the week, I am left simply to my classes. Knowing that all my friends are back at the dorm conversing with each other and having a good time makes me feel left out.”

Still, students are finding ways to maintain a semblance of normalcy — McCoy routinely calls both on and off-campus friends to socialize. He even looks forward to each day’s 11 a.m to 12 p.m. food delivery for low-risk social interactions with Residential and Dining Enterprises staff.

Benabou tried to maintain some sense of routine by continuing to work out for about an hour a day in his 20-foot by 10-foot apartment room in Munger.

Disconnect also comes literally for some students in off-campus housing — Kohler, an ECON 1: Principles of Economics teaching assistant, was kicked out of Zoom repeatedly due to WiFi issues and was forced to upload and send his students a recording of the material he could not cover in section.

However, not all aspects of isolation are bad, Kohler said. Off-campus students get $71 dollars a day in UberEats credit — he calls it a silver lining.

But the contrast between on and off-campus isolation can be stark. Benabou reported being given a moldy bagel, oatmeal with no bowl and overall smaller portions of dining hall food in his meal deliveries.

As the University’s pandemic situation progresses and policies evolve, students in isolation said they hope decision-makers will keep their input at the heart of the discussion. And while they still live in isolation, they eagerly await their return to campus life.

McCoy wrote, “I find myself counting down the days until I can walk free again.”