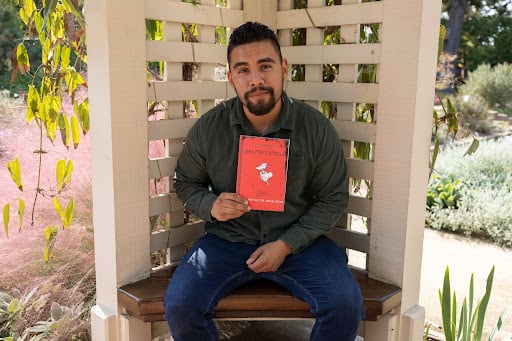

Antonio de Jesús López — poet, East Palo Alto City Councilmember and Stanford Ph.D. student in Modern Thought and Literature — begins his latest poetry collection with the definitions of a word he invented and uses as the title of his book, “Gentefication”:

- “when gentrification becomes personal, and the poet as native subject must invade language itself, when mobility just isn’t enough, and the poet must populate the canon itself from within;

- “when the poet finally decides to smuggle a metate inside English & por fin beat the shards that’ve barbed his mouth. and out bleeds from barrio stone, this molcajete alchemy;

- “stained saints of glass, fluent in the language of cut.”

These definitions provide a lexical foundation for the collection’s commentary on the politics of language and the nuanced relationships between home, injustice, education and community. López’s poems exist as antitheses of gentrification and phenomenologically resist it. They expand community and language, rather than regulate them.

In an interview with The Daily, López provided a clear roadmap for his collection. Throughout history, the English language has inflicted trauma, and oppressed and colonized marginalized communities. In his poetry, López aims to expand his readers’ understanding of what gentrification looks like, how being gentrified affects the human psyche and how an individual’s body suffers for it.

“I wanted to see what that meant for me,” López said, “What do relationships with language look like for a first-generation, low-income college student? Someone from a Latino background? A child of immigrant parents?”

Gregory Pardlo, Pulitzer-winning poet who wrote the foreword for the collection and selected Lopez’s work for the Four Way Books Levis Prize, also commented on how gentrification — as well as its absurdities and abuses — is displayed in the collection. “We’ve seen [these forces] descend on our neighborhood like weather systems. I found the moral clarity — which is not to say moral purity or rectitude — of ‘Gentefication’ liberating and revelatory,” Pardlo wrote to The Daily.

Amid his reckoning with the maneuvers of language, López tries to make the English language something that can restore us — as poets and as people — through his work. He refers to this process of using language as a vehicle for change as “people-fying,” essentially the direct translation of “gentefication.”

Pardlo notes López’s humanizing voice in his introduction to the book as well — indeed, “Genetification” imagines a world where everyone has the right to exist. “American literature has a history of erasing and ignoring parts of the population to suit its dominant self-image,” Pardlo noted. “Not everyone may see themselves in Lopez’s poems, but his poems are so largehearted that, in them, I think everyone can feel seen.”

Growing up in East Palo Alto, López refers to himself as the “nerdy kid in an environment of change.” Reflecting on his upbringing in a working-class family, he said that he disapproves of the romanticization of poverty and the “rags to riches” narrative of the American Dream. In reality, López explains, he and his community made the most of what they had, and he constantly observed the problems that existed in his community.

“There are these shadows, these pockets of poverty. I grew up in Silicon Valley, in a place that did not look like ‘The Silicon Valley.’ And being in that proximity to wealth made me wonder why things were this way,” López said.

López’s background also inspired his current role as East Palo Alto’s youngest city councilmember. He never intended to enter the political sphere, but the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic, as well as the wealth and health disparities it has revealed, catalyzed his own youth-led, grassroots campaign.

López said that the pandemic “was a call to action — COVID made me uncomfortable.”

His time at higher education institutions also greatly contributed to the composition of “Gentefication.” López, who has earned degrees from Duke, Oxford and Rutgers, is currently attending Stanford, and commented on how education was commended in his Latino family for its relations to generational wealth and socioeconomic mobility. In other words, the poet explores how “Lantindad has not only a question with immigration but also in education.”

“It’s not just a thing for an individual,” says López, “but education is important for your entire family and community.”

For all of its benefits, López finds that education is actually a fraught environment for people of color (POC), overshadowed by an idealized vision of academia. López emphasized that POC must therefore endure the violence inflicted on them by institutions and navigate systems that were not designed for “those who look like him.” In his first poem, “A Chicano’s Self-Help Guide to Racial Trauma,” we bear witness to a Latino student’s feeling of powerlessness caused by a white teacher. The speaker proceeds to run to the bathroom to vomit, a visceral reaction to reject the toxic attitudes that tokenize him and limit his personhood in the classroom.

Ryan Murphy — director of Four Way Books, the company that published “Gentefication” — and Hannah Matheson, publicist and an editor, believe that “Source E: Conjugations of My Tía’s Back” is a stand-out piece. To them, it “demonstrates the formal ingenuity, linguistic dexterity and rhetorical verve that define López’s poetry.” These traits of his work wield “the rules” of formal poetry to subvert them, highlighting institutional claims of education as an avenue of social change but also a place that instills elitist community structures and the prejudiced criteria for the value of art.

Appreciating the narrative and language in the poem, Murphy and Matheson note that the continually shifting perspective exemplifies the rote exercises of academia. Their interpretation is that the mechanism is used to “interrogate the overarching forces that shape our personal experiences and to demand tangible change.” The poem, ending in the “tú” perspective — the informal Spanish pronoun for “you” — allows for intimate confrontation as the speaker looks right at its audience.

“And you, the poem asks, the student in workshop, the reader holding this book, what are you going to do? The propulsion of this poem, as that of ‘Gentefication’ as a whole, transcends philosophical critique and lifts off the page, asking its audience to listen, to learn and to not just think, but to do something,” Murphy and Matheson wrote to The Daily.

These poems, like others in the collection, are written in “Spanglish” — mostly English with a sprinkling of Spanish words. López — while he used Spanglish mostly growing up — was at first shy to include any Spanish in his writing but later learned to embrace it, creating colorful and special images with the language.

His use of Spanglish and colloquialisms allows him to replicate his personal struggles with craving wealth and social mobility, pursuing education in dominantly Anglo-American spaces and learning to prioritize using English. He thereby evokes empathy in his readers for those who learn to exist and operate under the confines of a language not truly their own. López also asserts that his use of a non-English language in his writing is as much an intellectual choice as it is a political one — being holistically himself does not make him any less intelligent than his white colleagues.

With his poetry book, he hopes readers are compelled to reclaim space and use their voices, both in their academic settings and in the world outside of college. López provides commentary on how higher education is “a double-edged sword, and [that he] is trying to show one side.” His audience is not limited to students; instead, he aims for everyone to understand, and creates discomfort to inspire change. Lastly, using literature as a political device, he hopes readers can appreciate his art and use their own art to define and represent their communities.