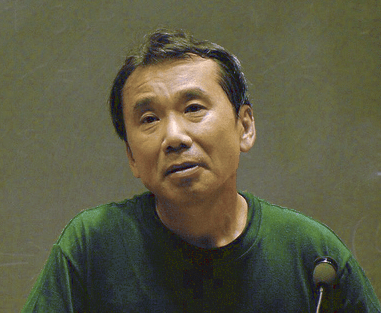

Before its release, I anticipated with eagerness Haruki Murakami’s new short story collection “First Person Singular” — published in April this year and translated from the Japanese by Philip Gabriel. But, upon reading, I ultimately found myself disappointed.

“First Person Singular” is a collection of eight short stories. True to its title, these short stories are all narrated in first person singular and, more often than not, by an unnamed, middle-aged man grappling with loneliness. Murakami seems to treat his characters as nothing more than symbols. The women in his stories are enigmatic — they perplex the narrator, and through the narrator’s perplexment, Murakami guides the story to some greater truth about the nature of loneliness, nostalgia or intimacy.

“I’d like to tell a story about a woman,” begins the story “On a Stone Pillow.” “The thing is, I know next to nothing about her. I can’t even remember her name, or her face. And I’m willing to bet she doesn’t remember me, either.” The story then goes on to depict a sexual experience that the narrator had with the woman. By the narrator’s own admission, his experience with the woman was unexceptional; it was a chance encounter between two acquaintances. One of the only things of note, the narrator muses at the end of the story, are the teeth marks that she left on his towel, which she bit into as she orgasmed.

Perhaps in an attempt to achieve a sense of relatable averageness in his stories, Murakami utilizes this form of characterization quite ubiquitously across the collection. Side characters are entirely ordinary with the exception of a single specific, strange detail that allows them to linger in the narrator’s mind. In “On a Stone Pillow,” it is the woman’s teeth marks on a towel. In “Carnaval,” it is how “singularly ugly” a woman named F* is. In “With the Beatles,” it is a disorder that a young man has that causes him to occasionally lose long stretches of his memory — a disorder that miraculously disappears after the narrator’s chance encounter with him. In each of these cases, the narrator bears a sense of fascination towards these characters and their idiosyncrasies, yet he is not attached to them. Certainly, they seem to care more for him than he does for them.

There is something at once humbling and grandiose about the narrator of each story. He lacks a clear identity and is often lonely and aimless, yet is given a godlike position in these stories. Women are inexplicably intrigued by him: It is not that they are necessarily in love with him, but rather that they are engrossed with him, even when — as with most of the stories in this collection — they are strangers, perhaps vague acquaintances. In the titular story “First Person Singular,” the narrator is alone at a bar, reading a book. An unnamed woman approaches him, seemingly without any provocation, and asks him, “What’s so enjoyable about doing things like that?”

Even if Murakami’s goal is to write stories that encapsulate loneliness — to portray a relatable human emotion in all of its iterations — I don’t believe that it’s sufficient to simply depict the people in his stories as unable to be understood or inherently confusing. A character doesn’t understand the narrator; the narrator doesn’t understand her. Therefore, the narrator cannot be anything but lonely and aimless, and the reason for his loneliness and aimlessness is quite simple: He is constantly surrounded by irrational people with whom he cannot find true connection.

What is the point of writing these mysterious characters — these unexplainable happenings, these strange occurrences — if there is no real attempt to prove that they are anything more than simply mysterious or strange? His story “Confessions of a Shinagawa Monkey” centers on the narrator’s encounter with a talking monkey who is exclusively sexually attracted to human women. Due to his lack of success with finding a sexual partner, he turns to stealing the names of women; that is, the monkey exercises a supernatural power that allows him to partially erase a woman’s name from her memory and keep the name for himself.

The narrator, upon hearing the monkey’s story, is perplexed. As the reader, I also find myself perplexed. By the end of the story, the narrator decides to write out his encounter with the monkey as fiction. In a moment of rare self awareness, he admits that there is truly no theme to this story: “It’s just about an old monkey who speaks human language, in a tiny town in Gunma Prefecture, who scrubs guests’ backs in the hot springs, enjoys cold beer, falls in love with human women, and steals their names. Where’s the theme in that? Or moral?”

Ultimately, Murakami’s collection features stories that may certainly be interesting or unusual, but do not venture beyond that. It is not enough for Murakami to, through his narrator, proclaim that these stories are meaningless or ordinary or simply strange. The act of writing inherently prescribes significance to a story. If a story is truly meaningless or ordinary, why write it at all?