Riva Quiroga, a managing editor at Programming Historian, a multilingual publication platform, said that publishing continues to exclude the work of individuals who are not native English speakers. This is especially true, she said, for the digital humanities — a field that uses computing and digital tools to further analyze disciplines within the humanities.

She explored the evolving nature of multilingual publishing, and her experience with Programming Historian, at “Multilingual Publishing in the Digital Humanities,” an event co-hosted by the Center for Spatial and Textual Analysis (CESTA) at Stanford University and the University College London’s Centre for Digital Humanities on Wednesday. The event is part of a transnational seminar series, “The Digital Humanities Long View.”

“Being a multilingual project is more than just publishing in different languages, it has more to do with how you understand what a language is and what it involves in terms of culture and power,” she said.

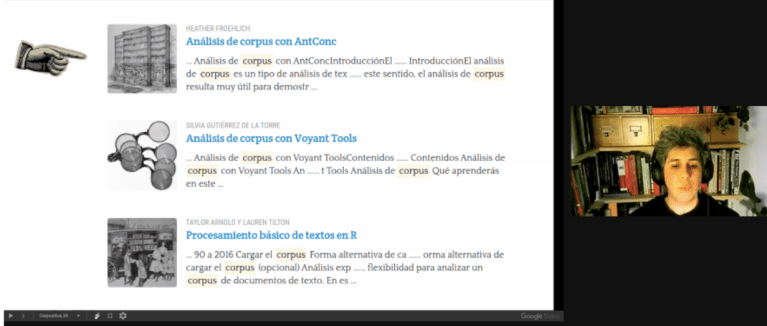

Programming Historian posts tutorials on the website that teach individuals the skills necessary for the digital humanities. Most of these skills include data analysis in open sourced computing platforms such as R or Jupyter Notebook, which allow users to run statistical models, create data visualizations and transform data.

“There are many tutorials about how to create a Jupyter notebook, but most of them don’t take into account how someone in the humanities might use that platform,” Quiroga said. Historians, for instance, are using Juypter notebooks for text analysis to explore linguistic trends.

The site has content in English, Spanish, French and, most recently, Portuguese. Without these translations, according to Quiroga, only English speakers would be able to join the global digital humanities conversation, leaving out entire groups of people who aren’t able to contribute as much to the field due to language barriers.

“Translating helps us fill the gap between the digital skills needed by humanists in the non-English world, and the learning resources that already exist, most of them only in English,” Quiroga said.

Quiroga’s comment comes at a time when, despite an increasingly interconnected world, she thinks language barriers make it difficult for the work of non-native English speakers to get published. And, not everyone is keen on helping make the space more inclusive.

This February, a controversial tweet by a co-editor at the Journal of Contemporary History, Richard Evans, revitalized this conversation. Evans tweeted that in 2019, 26% of submissions to the journal were accepted, and in 2020 17% were accepted. He said the main reason submissions were rejected was for poor English.

Evans’ tweet drew criticism from many individuals, including Quiroga, who said the tweet fails to acknowledge the privilege that comes with being able to communicate fluently in English.

But some Twitter users commented that it was “lazy” of those who do not speak English well not to “bother to have it checked by a native speaker before they submit an article to an English language journal.”

Quiroga finds this sentiment offensive, as she said it “equates laziness with the lack of opportunities and financial means to learn to speak English.”

She later researched the submission guidelines for the Journal of Contemporary History and found nothing stating that the journal is looking for a specific type of English. She said journals need to explicitly state which language varieties they accept for their submissions on their websites.

For Quiroga, making the publishing industry more inclusive is an area she will continue to promote at Programming Historian and said she is grateful for the opportunities that being part of Programming Historian and the multilingual publishing space have given her.

“[Programming Historian’s publishing] embraces language, cultural and gender diversity, and it was this publishing model that finally put me on the map,” she said.

This article has been corrected to identify the Center for Spatial and Textual Analysis (CESTA) at Stanford University and the University College London’s Centre for Digital Humanities as the event co-hosts. The Daily regrets this error.