This article is based on a more detailed technical paper by the author which was inspired by his experience in Math 51. The paper can be found here.

Pajama pants, students rolling out of bed and, of course, the omnipresent gallery of blank Zoom profiles. Over the past few months, these images have become quintessential fixtures of my remote learning experience in Math 51. But as the past fall quarter progressed, I seemed to see fewer and fewer pajama pants, sleepy students and blank Zoom profiles showing up to class. While a modest decline in attendance is expected in the closing weeks of any quarter, the drop was particularly evident this past fall. I was motivated to dig into the data to understand why.

Math 51 instructor Professor Christine Taylor said that “[attendance] dropped off significantly during the quarter… attendance always drops, but [the drop] for in-person classes [is] not as low as online.” This drastic drop in student retention and engagement is particularly troubling as recent resurgences of COVID-19 threaten to prolong this period of remote learning. Although concerns regarding student retention and engagement have accompanied remote learning since the start of the pandemic, these concerns have understandably intensified. To this end, I looked into how students’ preferences for synchronous and asynchronous lectures have changed and how those preferences may evolve during an extended period of remote learning.

I chose Math 51 due to the class’ rich set of synchronous lecture options (8:30, 11:30, and 2:30), its relatively large roster (414 students) and its status as a requirement for a variety of majors. These traits are favorable since they likely produce a sample of students that span different time zones and majors. Still, Math 51 is only a single class and is not fully representative of the student body, so any generalization of my analysis should be taken with a grain of salt.

Attendance Performance

As shown in the above chart, the three lectures seem to follow a consistent pattern. The attendance of each section begins with a steady decline in the opening weeks. It then becomes much more turbulent as the quarter progresses and levels off near the end. While the data conclusively shows a general decline in attendance, the trend is not constant. The data show a sudden shift from a steady decline at the start to a turbulent mid-section and gradual taper toward the end. This pattern raises a question of what might have contributed to the volatility observed across all three lecture times.

Upon closer inspection, the turbulent nature of the data appears to be strongly correlated with key academic events. Sharp drops in attendance (blue), for example, accompany the final study list, the term withdrawal, and the change of grading and withdrawal deadlines. Similarly, noticeable declines in attendance also accompany each of the nine homework due dates. Conversely, considerable increases in attendance (light grey) accompany lectures leading up to one of the five quizzes.

Despite these periodic rebounds in attendance, the substantial overall decline raises concerns about student retention, engagement and learning. Like most quarters, students that didn’t attend lecture either watched a Panopto lecture recording or skipped class altogether. But unlike most quarters, the share of students watching recorded lectures was much larger than usual. While the share of students that skip class and students that watch Panopto typically fluctuate depending on key academic events, those shares remained consistently high throughout the quarter.

As shown in the below chart, Panopto video quickly converged to a relatively stable share of between 80 and 90 students after the final study list deadline. The share of students that may have skipped, however, grew until the antepenultimate week where it converged to an unusually high share of between 150 and 160 students.

These shares remained relatively stable during the latter weeks of the quarter, save for the final week (lectures 28 and 29) which featured a significant decline of Panopto viewers and a spike in students that may have skipped. While the catalyst behind this sudden shift is unknown, it’s likely that incentives unique to the final week — no new material was covered — may have contributed. Due to privacy rules that anonymize the data of asynchronous options, the share of students that may have skipped class is extrapolated based on historical trends and therefore has some uncertainty.

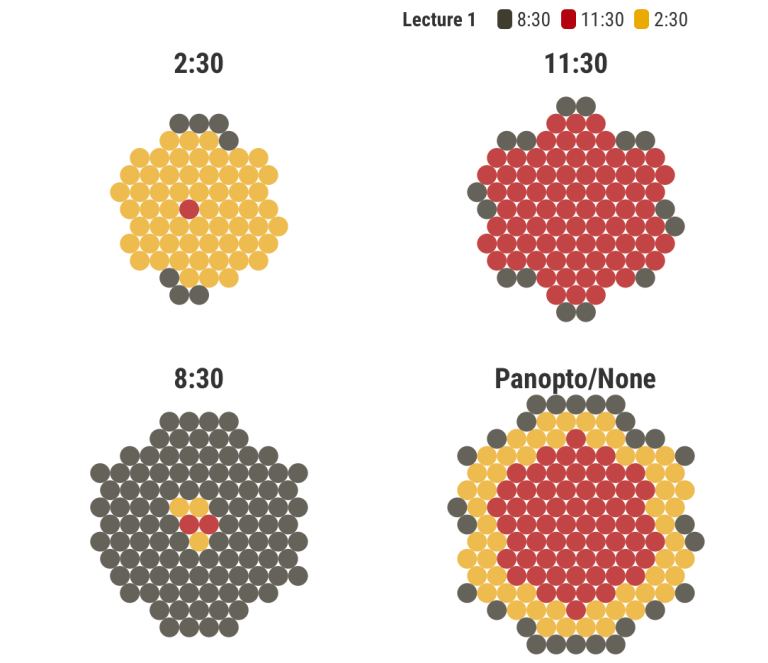

So, what would a more precise representation of students’ lecture choices look like? Considering the aforementioned privacy limitations, we created the below simulation based on a Markov matrix derived from Math 51 attendance data. It should be noted that the Markov model is based on partial and anonymous Panopto data and many simplifying assumptions. Class preferences, for example, are assumed to remain constant when in truth, preference for synchronous and asynchronous lectures are influenced by key academic events. In this regard, the simulation is akin to a line of best fit; the model can capture the overall trend, but it might omit nuances in the data. Thus, this simulation should be taken with considerable caution but may still capture general trends.

In the simulation, each student (represented by a circle) chooses a class to attend based on a probabilistic model of their previous class. A student that previously attended an 8:30 section, for instance, has an 86.5% probability of attending the next 8:30 section, whereas a student that previously attended a 2:30 section only has a 0.6% chance of attending the next 8:30 section. Over the simulated quarter, students move around the different sections based on this model, just as a student might attend different sections during a quarter. By the 20th lecture each of the four sections has largely stabilized, which indicates that the sections have achieved an equilibrium state. The characteristics of these sections — size in particular — suggest how student lecture choice might turn out during an extended period of remote learning.

What does this mean for me?

Does the rise of recorded lectures through Panopto mean the agony of waking up for early 8:30 am classes will soon be relegated to the past? As much as we want a guarantee to regularly sleep in, the novelty of Zoom-based live classes makes it difficult to arrive at any definitive conclusion. Luckily, there’s a department that has been running this experiment for the better part of a decade.

“In the CS [department], classes are recorded so they’ve been ‘Zooming’ for almost a decade and we believe their live attendance was low prior to the pandemic,” Taylor said. Although fewer students attend synchronously, these recordings have enabled students to revisit topics they aren’t comfortable with, study for other classes without missing lecture and have improved accessibility for students with external limiting circumstances.

Still, despite these merits, Taylor believes the widespread use of asynchronous options — like in the past spring and fall quarters — could create a culture where students regularly skip synchronous class in the future. This is particularly problematic for frosh who have started college watching and becoming comfortable with Panopto and may be more prone to continue learning asynchronously and skipping future classes. But this might not be limited to just Panopto viewers. Even students that regularly attend synchronously could become inclined to attend lectures through Panopto if a significant portion of their peers are.

The rise of recorded lectures also raises a question of the impact on students. While the effect on learning is still inconclusive, “students that just attend classes on Panopto video may not be as well connected with the class,” Taylor said. “When it comes to needing a reference letter, for example, an instructor is going to [have a hard time writing] for someone they’ve never seen or heard from in class or office hours.” Additionally, lower synchronous participation could limit valuable feedback which, in the context of Math 51, has been used to amend the class textbook, the material covered in lecture and the grading policy last fall.

To this end, forgoing synchronous lectures “could be detrimental to students’ education and professional development,” Taylor said. Still, Taylor understands that some students simply cannot attend lectures synchronously while not being on campus, so they encourage students to engage with faculty and other students during office hours. And, with some luck, it’s possible that students who didn’t attend lectures in the fall may start attending lectures synchronously in the winter. “It must be so demoralizing and isolating to always stare at a computer by yourself, so I hope students will appreciate the face time,” Taylor said.

Should Stanford be a Zoom- or Panopto- University?

The prospect of an enduring “Zoom University” has been entertained since the start of the pandemic, but has become the point of more serious discourse in recent months. Our results suggest that in just a few weeks, a majority of Math 51 students preferred the asynchronous Panopto recordings to the synchronous Zoom classes, and that students will continue to stay with Panopto in the future. While there may be some complications associated with this sudden shift to asynchronous learning, the benefits of Panopto observed in the CS department could prove vital, especially as a supplementary resource for students.

Assuming Zoom and asynchronous alternatives like Panopto video are sufficiently effective, considerations about future class sizes and when certain classes are offered, for instance, could be altered to accommodate more students. Such changes could prove extraordinarily helpful in providing regular access to niche classes, assisting smaller departments, and accommodating students in varying time zones, like student athletes and international students. Still, since my results stem from the lecture preferences of Math 51 students, more research about the effects of asynchronous alternatives on other classes is needed before the prospect of an enduring Zoom/Panopto University can zoom into a reality. Well, in this case, maybe one pajama pant, sleepy student and blank Zoom profile at a time.

Contact Benjamen Gao at bengao10 ‘at’ stanford.edu.