This article is part of a series of profiles of Stanford alumni in politics. Click here to read the rest of the stories.

For Andy Berke ’90, being mayor of Chattanooga, Tennessee, was never the plan. “I did not want to run for mayor,” he said. “I told all my friends that I was not going to be the mayor.”

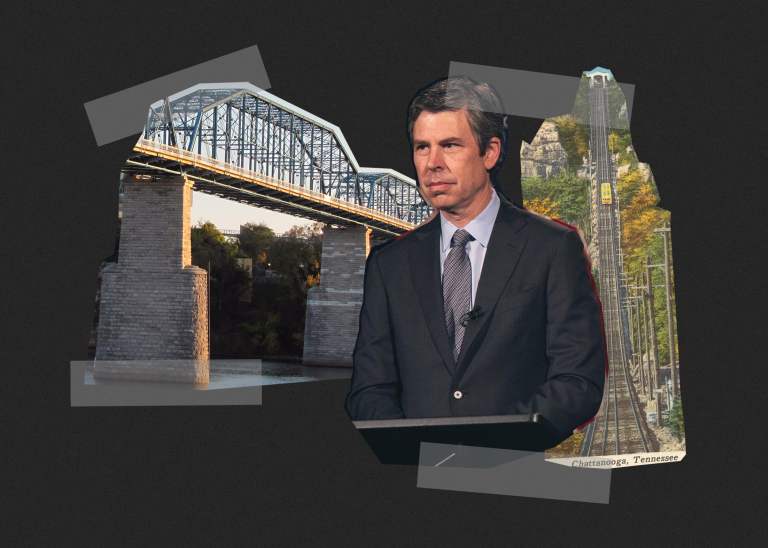

And yet, here he is, in the last few months of his second term in office, having served since 2013. While in office, he has seen both crime rates and unemployment rates decrease, restructured the city government and responded to a terrorist attack, a tornado and now, a pandemic.

Berke arrived at Stanford in 1986 from Chattanooga, where he was born and raised. At Stanford, he found himself in a completely different environment, one much more diverse — in background, interests and talents — than his hometown.

“I loved my years at Stanford,” he said. “They were as formative as anything that has happened in my life.” For Berke, it was the community he found that had a lasting impact on him, much more than the academics. “I enjoyed so many activities because it would regularly bring me in contact with new people and ideas, and in the long run, those became friendships and skills.”

Berke kept a busy schedule at Stanford. From his very first week, he tutored kids in East Palo Alto. He was also active at the Haas Center for Public Service and with the Associated Students of Stanford University (ASSU), working as the director of the ASSU Speakers Bureau in his junior year. A Daily article described his goal to “bring interesting and informative speakers who may at times spark controversy.”

Berke even wrote and edited for The Daily in his senior year. The Daily divides its volumes with two volumes per school year, and prior to the start of his senior year, Vol. 196 Editor-in-Chief Tim Marklein ’91 asked Berke to join the editorial board because of his broad involvement on campus.

“I had never really been excited or thought about joining The Daily, but I was passionate about sharing my viewpoints about what was going on,” he said. So, he said yes. As part of the editorial board, he would write one or two of the editorial pieces each week.

Midway through Berke’s senior year, as Volume 196 was coming to a close, the incoming editor-in-chief John Wagner ’91 “called me up and said, ‘Would you be the opinions editor for the rest of the year?’ And that sounded fun and interesting and different, and so I said yes and got to learn a lot about the inner workings of a newspaper.”

Even today, Berke carries his time at Stanford with him. He met his wife Monique Prado Berke ’89 MBA ’95 while at Stanford, and one of his two daughters, Hannah Berke ’22, is a current Stanford student.

Berke graduated from Stanford in 1990 with a bachelor’s degree in political science, after which he worked for Rep. Bart Gordon (D-Tenn.) as a legislative assistant. He then went on to law school at the University of Chicago, graduating with a law degree in 1994. After a stint clerking for a federal judge on the Tenth Circuit Court of Appeals, he decided to return to his hometown. It was, he realized, his best option — a good place to live and practice law, and somewhere he thought he could really make a difference. So in 1995 he moved back to Chattanooga and joined his father and his uncle at Berke & Berke, the law firm his grandfather had started.

While practicing law, he began to get more and more involved politically out of a sense of duty for his community. “At some point I decided that it wasn’t enough to help people one at a time,” he said. “I wanted to see if there was a chance to take that to scale. I had always been interested in politics and elections. I had studied a lot about government, and so I started volunteering more and more for different candidates and seeing what it took to run for office.”

Eventually, he came to the realization that he himself could run for office. “Over the course of time I started to see, well, these are just people who are doing the best that they can,” he explained. “They have no magic secret that I lack, and so I’ve just got to get out there and do it. I wanted to make things better in my community and across Tennessee, and I figured I could do it a lot quicker in elected office than I could from my law office.”

So, when there was a special election in the 10th Senate district of Tennessee’s state legislature in 2007, Berke threw his hat into the ring. He won the Democratic primary and went on to face off against Republican Oscar Brock ’85, a fellow Stanford alumnus and the son of former U.S. Secretary of Labor Bill Brock. Yet, even given Brock’s familial bona fides (his great-grandfather had also been a U.S. senator from Tennessee), Berke won the race with more than 60% of the vote. A year later, he was reelected in the regular general election, this time with more than 70% of the vote.

During Berke’s tenure as state senator, there were discussions in Chattanooga on how to respond to an uptick in gang violence. However, Berke found some of the floated fixes lacked the ability to enact real change. “I thought that some of the local solutions that were being proposed and some of the things that were being said were unlikely to help anybody, and I was upset to see so many people getting shot in my hometown,” he said.

In response, he decided to write an op-ed giving his perspective on the best path forward. But as he sat down to write, he came to a realization. “I thought to myself, all your friends are telling you to run for mayor and you’re telling them no. Now you’re going to write an op-ed about what the mayor should do,” he said. “Instead of criticizing from the sidelines, maybe it’s time to to put those ideas into action. And so after telling everyone that I was never ever going to run for mayor, within a week or two after that I was all in to win the election.”

In 2013, he was elected mayor of Chattanooga with over 70% of the vote. Now, the job he once thought “seemed like a really hard job where you made people angry on a regular basis” was his.

(Responses have been edited for length and clarity.)

I think my enduring memories of Stanford involve sitting in my dorm room with other people, some of whom were close friends and some of whom probably weren’t, talking about the issue of the day — oftentimes arguing about the issue of the day — at all hours of the night, feeling like that was the most urgent thing that I could be doing.

Right now the biggest problem people are facing is COVID-19 and the incredible inequities that have been exacerbated since it came to our shores. COVID-19 has devastated our community. It has caused financial hardship, health issues and spiritual and mental health problems for people in our city. That has been mainly focused on people of color and also individuals who are at the lower end of the economic spectrum. For approximately two months as the pandemic began, we were seeing numbers that were incredibly disparate compared to our population. Our county is about six percent Latinx, and for roughly two months about 60 to 70 percent of our cases in the county were Latinx. So you had this disparity between who was suffering the most and who was in our community. On top of that, the businesses that have felt the brunt of COVID have tended to be small businesses and businesses owned by people of color. They didn’t have the reserves built up to come out of the shutdown and function. On top of that, when your employees have to be out either once or several times because they’re quarantining, it makes it extremely difficult to operate your business. So while our larger businesses have actually rebounded rather quickly, you have this entire swath of the city where people are really feeling the impact of coronavirus.

I’m actually more idealistic now than I was when I ran for office the first time. I think that the possibilities are endless, and that it takes courage to be vulnerable enough to imagine the best. The cynicism about public service is what leads to bad people getting elected, so I refuse to be part of that. I hope that I’ve made a difference; I feel confident that certainly there are some places that I’ve seen true success, but there is lots more to do both in my city and across the country, and tremendous leaders make things better. I think all I would say is that, particularly out at Stanford, there’s a huge focus on innovation, and innovation as it relates to tech. But innovation in policy and government is also enriching and satisfying, and I would urge all students to think about ways they can make a difference, whether that’s directly in governmental service or as a contributing member of the community.

In March, Berke was one of the earliest officials in the South to take measures to limit the spread of the virus, with the Republican Governor of Tennessee Bill Lee following about a week later. But then, at the end of April, Lee reopened the state, and in the process overruled city-level officials like Berke, much to his frustration.

“We’ll never be normal as long as coronavirus is a problem in our city. We can pretend to ignore it, but that doesn’t really solve any problems,” he said when asked about those pushing for complete reopenings. “We can act as if it is all about politics and just what elected officials say, but the reality on the ground is that the COVID-19 takes its own course.”

Relatedly, Berke readily criticizes the Trump administration’s handling of the pandemic. “In public health emergencies, the most important thing is clear communication,” he said. “Instead, what we have is misinformation, contradictions and a lack of guidance.”

At the moment, Berke’s number one wish for a pandemic response is simply “a national plan.” Even if he had all the power to implement any measure he wanted in his city, Chattanooga is not an isolated locale. “There are many things that I would like to do,” he said, “but in the long run, we’re all fishing in the same pond. And so we have to figure out the right policies.”

In particular, he mentioned guidance on schools, sensible mask mandates and economic support as focus areas. But underlying this all? “We have to listen to science rather than politics when it comes time to make decisions,” he said. “I remember Dr. Fauci from his influential work on curbing AIDS, and the idea that he and science would become a political football to be kicked around is unimaginable to me when lives are at stake.”

Even before the election, Berke was confident that Joe Biden would win the presidency. He specifically points to the misinformation Trump has spread regarding COVID-19 as a reason. “The lack of truthfulness and the divisiveness have hurt him even among people who were inclined to support him,” Berke said.

He also points to Biden’s themes of unity as one that he believes resonates with voters. “He consistently says that he’s going to make policy — not for red states or blue states, but for the United States,” Berke said. “That’s what I want in a leader.”

It is also the kind of leader Berke tries to emulate, stressing his responsibility for the people in his city regardless of party affiliation or lack thereof. He mentions Biden’s empathy, too, as an important trait for a leader before detailing his own experiences interacting with his fellow Chattanoogans. Before COVID, he said, he loved going on walks and hearing firsthand what people had to say.

“One of the most impactful things about being in public office is when somebody shares their story with you,” he said. “It makes you want to overcome any barrier out there to make the world a better place for them because they’ve shared something that’s incredibly personal and sometimes sad or oftentimes hopeful, but always impactful.”

After Berke’s 2017 reelection with over 60% of the vote, his second term is now coming to a close, and with it his time as mayor; he is only allowed to serve two consecutive terms, and in March, Chattanooga will choose a mayor to succeed him. “I hope that I’ve made a difference. I feel confident that certainly there are some places that I’ve seen true success, but there is lots more to do both in my city and across the country,” he said of his time in office.

What next, then?

“Does The Stanford Daily need an opinions editor?” he joked, smiling widely. After the banter subsided, he went on to admit, “I don’t know what will happen next.” No matter where he ends up, though, he knows he is drawn to roles in which he can make positive change. “I truly enjoy being part of the process and seeing things change and improve even when there are seemingly insurmountable barriers,” he said. “The drive to tear them down gets me up in the morning.”

As a Democrat in Tennessee, his paths to higher elected office are admittedly tough. But perhaps that is simply the next seemingly insurmountable barrier to tear down. Only time will tell.

Ari Gabriel contributed reporting.

Contact Evan Peng at pengevan ‘at’ stanford.edu.