Some current and former Cantor employees have been given first name pseudonyms to improve readability. Their identities, while known by The Daily, are being withheld in this article due to fear of retaliation for speaking out.

Riding in on Palm Drive, eyes tunneled on the Stanford Oval — if you didn’t happen to look to your right, you might not have noticed the sandstone building towering over Museum Way. The Cantor Arts Center — boasting the largest Rodin collection outside of Paris in addition to a respectable selection of artwork for its 130,000 square feet — is a world-class university art museum, and a museum destination in its own right. Yet, in most of the 125 years since the University first opened, the Cantor has fallen just short of being a popular student attraction.

At the beginning of the year, the Cantor installed a permanent, bright-yellow “OY/YO” sculpture at the foot of its front steps. Unmissable, Instagrammable and divergent from the rest of the Cantor’s intimidating neoclassical architecture, the piece was supposed to graduate the museum into the contemporary and help it embrace a 21st-century vision.

“It is intended to beckon,” said museum director Susan Dackerman to the San Francisco Chronicle in January, “to say, ‘Yo students, yo Stanford, yo Palo Alto, yo San Francisco, yo Bay Area, come see what we’re doing at the Cantor.’”

But behind that facade hides what many Cantor employees have called a toxic work culture, demoralizing museum leadership and a University administration that seems loath to substantively address repeated concerns — all circumstances that have been pushing employees out at an alarming rate.

The museum looks like it’s succeeding, a former employee at Cantor said — but its staff have become “workhorses” to recycled curatorial material and a management team that overlooks the talent and goals of the museum’s employees.

A revolving door

Since Dackerman’s arrival in September 2017, at least 30 Cantor staff members have left, more than a third of whom are Black, Indigenous and people of color (BIPOC), according to a document compiled and maintained by current employees. In the past year alone, 25% of the staff have moved on from the museum, according to a former member of the Cantor’s leadership team. Leadership wrote that they have been aware of the concerns, and had launched an independent review before being contacted by The Daily.

Employees left behind a diminished team of approximately 40 people, with many curatorial and managerial positions still unfilled, according to an organizational chart obtained by The Daily. (These positions will have to stay open until the end of the University-wide hiring freeze implemented in March due to COVID-19 financial pressure.)

People have been leaving faster than the speed at which others can be hired, said Morgan, an employee at Cantor.

Multiple Cantor employees expressed feelings of exhaustion and burnout, brought on by understaffing and “unreasonable” deadlines imposed by leadership despite employees’ protests.

“I cannot emphasize enough that the timelines that they had us working on were not museum-standard,” said Marsha, a former Cantor employee. Some exhibitions had to be completed in five months, some in weeks. An exhibition took several years when built for another institution, while the Cantor team was given six to eight months for its version of the same one.

And it’s not for lack of resources, Marsha added: At other universities, “the arts are generally stifled because they’re underfunded — Stanford does not have that problem.”

“I think there were more risks taken than we wanted and less time to conduct nuanced research,” Marsha added. “This is not unheard of, but it does not feel right, [since] we take on the responsibility of facilitating interpretation of visual culture.”

But the workload alone doesn’t explain why some employees left, and for some it wasn’t even the final straw. Even if it were normal, Morgan said, people in the museum field know they signed up for hard work, and know that museum jobs usually aren’t lucrative. Many of the employees The Daily interviewed noted that few places offer the resources and competitive benefits that Stanford and the Cantor does.

“You’d have to really push people in the museum world for them to leave here,” Morgan added.

When Dackerman was first hired, she spoke ambitiously of plans to reimagine the Cantor’s more outdated aspects and to make the museum more central to campus life. At Silicon Valley–facing Stanford, she wanted the Cantor to reflect a communication revolution, showcasing not just aspects of the world we live in, but how we navigate and find ourselves in it.

Dackerman’s pitch to change the Cantor for the better was what convinced Peter Tokofsky to take on the newly minted role of director of academic and public programs in June 2019. The position was created to help remedy students’ perception of the Cantor as irrelevant and turn the museum into an engaging community resource.

So, in addition to the “OY/YO” sculpture, the Cantor also redirected efforts into growing attendance at First Fridays (art-focused social events held on the First Friday of every month) from fewer than a hundred students to 400 strong by March. The Cantor hosted its first FLI and LGBTQ+ runway Self-Fashioning Show to great student reception. Tokofsky said that Stanford class visits increased by 35% during his tenure.

In the six months before the University shuttered due to coronavirus, the Cantor had started to prove that, while “on the edge” might have been where the Cantor was physically located on campus, it didn’t also have to describe where it was positioned in student life.

And with that tremendous progress in student engagement and interest, “it’s easy for University leadership to act as though there is not a problem at Cantor,” Tokofsky said. “But what they don’t acknowledge is that this progress was made despite significant internal challenges” — resistance from certain members of the leadership team “at every turn.”

Staff point specifically to Dackerman, Deputy Director and Chief of Staff James Gaddy and Communications Director Beth Giudicessi as the main contributors to an unbearable and toxic work culture that, on top of the workload, was responsible for ultimately pushing out many of the staff.

“There’s such a big hierarchical gap between leadership and how everyone else works … it feels like that’s one museum upstairs and there’s another one downstairs.”

Dackerman and Gaddy rarely listened to the suggestions of staff or made them feel valued and respected, employees told The Daily. Gaddy himself was “dictatorial,” employees said, and decision-making was concentrated in the upper-management level and not communicated to staff. A former staff member said that Gaddy would hide budget information from people who needed it to do their work, and would speak negatively and unfairly about employees behind their back — “he would promote or intimidate people depending on how he feels about them, and so on.”

Dackerman did not respond to requests for comment, and Gaddy directed The Daily to a University spokesperson. The University did not comment on claims about budget transparency but had said previously that all hiring decisions are made in accordance with human resources and University policy.

“I feel like there is … a bit of this underlying toxicity … you feel like you’re always watching your back or don’t know if you’re going to get praised or reprimanded,” another staff member said in a document obtained by The Daily detailing staff responses to a survey.

Employees said they rarely felt empowered in their work, and didn’t feel as though Dackerman and Gaddy cared about their well-being or about creating a respectful workplace.

For one exhibition, Marsha had already been working well outside of their scheduled time to complete the work Dackerman requested. Marsha said Gaddy suggested they limit overtime by working through lunch or minimizing “other breaks,” which they rarely had.

“I was burned out and felt like these requests to save the institutional budget without changing the workload continued to overlook staff health,” Marsha said. “I can only remember feeling overwhelmed and having so few outlets to relieve the stress from my employer.”

For many employees, it just seemed as though there was a “lack of basic human decency” among some members of leadership. Combined with institutional misguidance, it contributed to what Jordan, a former Cantor employee, described as a “slow progression of making people miserable until they decide to go.”

Two employees specifically described a situation at the end of 2018: The former head of security was told he would be laid off just before he was set to receive a five-year benefit. They said he had kids who were waiting on that benefit so they could afford to go to school. He passed away a few months later.

The University said they could not comment on employment or disciplinary matters related to specific individuals, but told The Daily that all hiring and separation decisions are conducted in cooperation with human resources and in compliance with University policies. Gaddy later absorbed the head of security position into his own.

“It was heartbreaking,” Jordan recalled. “There’s absolute disregard for how hard people are working, how good they are.”

Cantor employee Alex said that “it was never really addressed except for having this awkward moment of silence for him. Then, business moved on as usual.”

Unsuccessful interventions

In October 2018, more than a year into Dackerman’s tenure, the University ran a cross-campus employee satisfaction survey. Employees said the results from the Cantor were so dismal that it sounded an alarm that made it up to the Vice President for the Arts (VPA) Harry Elam’s office. The VPA oversees the Cantor Arts Center, along with other Stanford Arts initiatives.

After he saw the results in March 2019, Elam showed up for a “listening tour” at various Cantor departments and initially made efforts to hold office hours and meet with small groups of staff members. Elam wrote in an email to all VPA staff that he took the results “very seriously.”

“At the time it was a shock to us,” Jordan recalled. “I don’t think Cantor leadership expected [that reaction], and it was like, gosh, things might actually get better.”

A University spokesperson, who did not agree to be identified, told The Daily that before the survey results had been released, the Cantor had already invited an outside organizational development consulting group to “provide guidance to advance the organization.” The group’s initial task was supposed to be strategic planning to “advance the museum towards accreditation,” but shifted to developing “work culture and productivity” per the consultants’ recommendation.

The process, set to begin in May 2019, would include surveys, focus groups, confidential interviews, various meetings and seminars and two all-staff retreats.

The consulting group compiled comments collected from staff and presented the redacted responses at the end of the first all-staff retreat in June 2019. (The Daily obtained a copy of the presentation slides.) Comments indicated a high level of cooperation and appreciation among Cantor staff. “My colleagues are great,” one employee said. “We (as staff) agree on many of the challenges and problems the museum faces,” said another. “We are all in the same boat.”

Even so, “Leadership and management, accountability and decision making” and “Culture overall” were two of the lowest-scoring categories: only 13% and 3%, respectively, of comments reflecting on either category were positive.

“There’s such a big hierarchical gap between leadership and how everyone else works … it feels like that’s one museum upstairs and there’s another one downstairs,” one employee wrote.

When Cantor staff and leadership got together for the first all-staff retreat, former employee Natalie recalled being hopeful: “We were willing to see the process through,” she said. “But every time management stepped in, they stripped [that hope.]”

Multiple Cantor staff recounted an instance from a leadership panel: someone asked a question about incorporating “a bit of fun” into the workplace to boost morale, “and Beth said that if it was fun, it wouldn’t be called work.” They remembered Dackerman as unreceptive to the process, and Gaddy as otherwise preoccupied.

The University did not directly address those perceptions of Dackerman and Gaddy and their participation during the retreats, but a spokesperson said that “those initial efforts to clarify roles and responsibilities, create accountability and elucidate decision-making processes have been effective for a significant portion of the staff.”

As for the interventions at a University level, Jordan said that Elam had been personally supportive and made genuine efforts to engage staff in conversation about how to make the work culture more tolerable — though those efforts ultimately fell short of substantive solutions. Most of the Cantor staff members The Daily spoke to agreed.

“I know he was trying — I know he was really trying,” Jordan said. “Maybe there wasn’t enough time; maybe it was the bureaucracy; maybe Stanford’s not enough of an ‘arts’ place.”

Elam left Stanford earlier this year in June for a new position as president of Occidental College in Los Angeles. He did not respond to multiple requests for comment.

No one could quite explain why Elam’s attempts to improve the Cantor work culture dwindled, but many employees believed that the University may have received mixed messages from Dackerman and Gaddy, deflecting blame on the staff for the Cantor’s problems. The University did not respond to these claims.

“Following the departure of several of these staff, I witnessed PR campaigns to deflect the criticism of leadership and defame the staff as incompetent, malcontent, or ready to move onto other pursuits,” Tokofsky wrote in a letter obtained by The Daily to members of the museum’s advisory board before he left in July.

He added that Dackerman instructed him to meet with University administrators to “counter characterizations of the Cantor by departing staff, rather than address their concerns.”

This narrative — which an employee described in a document obtained by The Daily as “a long history of leadership thinking the museum is inadequate due to an inadequate staff” — served only to engender a culture of “distrust and frustration.”

“It seemed like they were always pointing the finger at us, like it was us that needed to change,” Natalie said in an interview with The Daily. When several staff members left in just a few months, Cantor leadership “thought they had conspired to try and do it at the same time.”

A longtime donor told The Daily that Dackerman claimed to other donors and the museum’s advisory board that she had “inherited” the poor work culture from the previous museum director — but several of the people who left the Cantor recently were Dackerman’s own hires.

“It seemed like they were always pointing the finger at us, like it was us that needed to change.”

“The notion that these people don’t know what they’re doing, that [leadership] can come in and treat people horribly and blame the staff, does not hold water,” said Riley, an employee at Cantor. The rest of the Cantor staff are “all very inspired people, inspired by the mission, and proud to work at Stanford.”

The staff felt they were being silenced: Dackerman and Gaddy “were so much more concerned about … everything outward-facing, not the internal issues,” Natalie said.

Before the circulation of one email from a staff member that described issues with workplace toxicity, the Cantor’s employee-wide mailing list had been free of any permissions, and employees were allowed to send messages to recipients on the listserv, an employee said. Afterward, permissions were added so that messages had to be pre-approved.

After receiving notice from The Daily, Matthew Tiews, interim senior associate vice president for the arts, wrote in a July 17 email to Cantor staff, which was obtained by The Daily, that staff should not respond to contact from the media, and should instead refer requests to comment to Stanford Communications.

Tiews also notified staff in that email that the Cantor had already begun a separate “independent review” to “evaluate outstanding concerns and further the museum’s organizational endeavors” prior to receiving contact from The Daily. A University spokesperson specified to The Daily that Dackerman initiated the review upon learning of the circulation of Tokofsky’s letter.

Reportedly, the museum board, of which some members participated in the director’s search and helped hire Dackerman, wanted to cover up Tokofsky’s letter: “They were so concerned in making sure no one saw it,” said a person familiar with the situation.

Tokofsky’s letter detailed circumstances leading to his departure in July, when he said Dackerman chose not to extend his first-year trial period due to his “poor performance.” He believed that that reason didn’t tell the full story. Besides contributing to the popularity of student-facing initiatives like First Fridays, the Self-Fashioning show and class visits, Tokofsky also increased the number of partnerships with numerous University departments and faculty, he wrote. He also helped grow the Student Guide program and the docent program, all with three of six positions on his team vacant.

“Peter is a first-rate scholar and museum professional, who gained respect across campus among faculty, administrators and students,” said Ruth Starkman, a biomedical and computer ethics PWR lecturer who often interfaces with the Cantor for her classes. “Most importantly, he brought in more first-generation, low-income students of color than any other Cantor staff member.”

A flawed director’s search

The Cantor’s current work culture was perhaps a long time in the making, beginning with a “deeply flawed” job search process to fill the Cantor director position in fall of 2017, after the abrupt resignation of previous museum director Connie Wolf, according to a faculty member who witnessed the search.

“Susan Dackerman knew she was unqualified to manage a University museum” — that faculty member said that they had overheard Dackerman say so herself — “and the Stanford faculty [who participated in the search] knew this as well,” they added.

The faculty member added that one candidate who had prior experience as a museum director, a Ph.D. in art history and an MBA degree was “specifically rejected” by a member of Stanford’s art history faculty because the MBA degree didn’t align with the image of an “intellectual” that they wanted.

“The faculty were … persuaded by Dackerman’s Ivy League experience, comforted by her unpolished academic style,” the faculty member added. “This misguided thinking prevented Cantor from hiring experienced leadership with managerial skills and community savvy.”

Dackerman is by no means unfamiliar with art history or even university museums. She has undergraduate and doctoral degrees in art history, and worked as an assistant curator at the Baltimore Museum of Art fresh out of graduate school. In 2016, she spent a year as a consortium professor at the Getty Research Institute in Los Angeles, and worked on books about printmakers Albrecht Dürer and Jasper Johns. For a decade before that, she served as a curator at Harvard Art Museums.

But according to Cantor employees, her curatorial and academic experience hasn’t translated to successful leadership ability.

A University spokesperson wrote on Dackerman’s behalf that claims about Dackerman’s qualifications “stand for themselves,” adding that “since [her] arrival … numerous exhibitions, acquisitions and projects have garnered unprecedented national acclaim.”

“The director role oversees the programmatic functions of the museum — including all curatorial activities — and devotes whatever time necessary to accomplish those tasks and fulfill the responsibilities of the role,” the spokesperson added.

Employees also trace workplace toxicity issues to Gaddy, Dackerman’s right-hand man.

“To cover her incompetence, absenteeism and clumsy public persona,” Dackerman “bullied her employees to compensate, [using] Gaddy as her enforcer,” said the faculty member who witnessed the director’s search and in whom several Cantor employees have confided.

Before joining Stanford in May 2018, Gaddy left his positions as human resources vice president and Title IX coordinator at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts under the shroud of a mishandled Title IX investigation in April 2016, the Philadelphia Inquirer reported. In that case, it took approximately 130 days from complaint filing to dole out disciplinary action against the perpetrator — more than double the 60-day period that federal Title IX policy considers typical. Delays and allegations of foot-dragging were kept under wraps, according to the Inquirer.

“To cover her incompetence, absenteeism and clumsy public persona,” Dackerman “bullied her employees to compensate, [using] Gaddy as her enforcer.”

Afterward, multiple Cantor staff members expressed concern to The Daily that Gaddy was hired at Stanford despite the lack of clarity surrounding the circumstances of his departure from his previous job. Cantor’s 2018 press release about his hiring mentions that he served as a human resources executive at the Pennsylvania museum, with no mention of his role managing Title IX. The University did not respond to questions about his hiring.

Gaddy, hired to manage the Cantor’s “day-to-day operations” and to oversee “many departments including security, facilities, the café, visitor services, finance, collections, and exhibitions,” has a noticeable gap in experience with exhibitions and museum practices, despite being charged to manage much of the behind-the-scenes work of an art museum.

“With his wealth of experience and approachable personality, James will enhance our culture of innovation, inclusion, collaboration and teamwork,” Dackerman said of Gaddy in that press release. For many Cantor staff, that wealth has anything but materialized.

More than ‘lip-service’ diversity

Multiple Cantor employees who either had worked at other museums before or are now working at another museum maintain that the toxic workplace at the Cantor is by no means “normal.”

“We all have many friends that work in museums — we’re familiar with a lot of the characteristic problems of museum culture, its politics, the bureaucracy,” Riley said, “but I can tell you that the Cantor is unique.”

Even so, the reckoning that Cantor leadership is currently facing isn’t happening in a vacuum. The San Francisco Museum of Modern Art (SFMOMA) saw its senior curator, Gary Garrels, resign on July 13 due to racially insensitive comments about “reverse discrimination.” Garrels was the fifth high-level employee at SFMOMA to leave in a span of a few weeks, as the Bay Area art institution faces calls for structural equity and anti-Black racism accountability. He also follows a number of high-profile figures across the country who have resigned or left in a wave employee upheavals at art museums stumbling to address racism, harassment and abuses of power: Smithsonian’s National Museum of African Art, Detroit’s Museum of Contemporary Art and New York’s Guggenheim museum and Metropolitan Museum of Art.

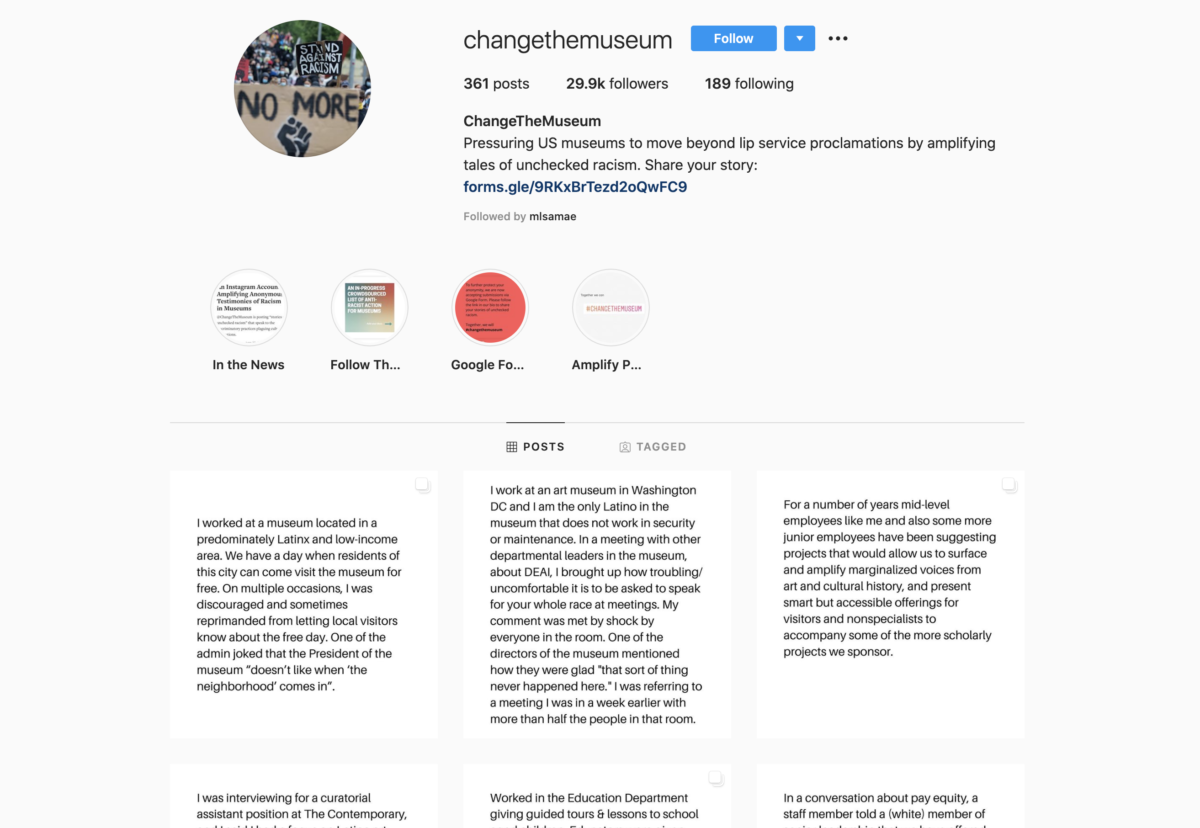

An Instagram account, changethemuseum, serves as a forum for museum workers across the country to post anonymous “tales of unchecked racism.” It has garnered close to 30,000 followers since its first post two months ago. The account hopes to pressure art institutions to “move beyond lip service proclamations” of support for diversity.

By most counts, the Cantor has been proactive about supporting exhibitions and collections that celebrate cultural diversity, a goal that Dackerman and Tiews have repeatedly articulated. But in the same vein of criticism museums nationally are facing, some Cantor staff say displaying works by artists of diverse backgrounds and cultures doesn’t cut it. It is not enough to feature works by artists of color, or to say that the museum showcases diversity and inclusion, or even to specifically hire people of color — if the museum isn’t actively working to cultivate a positive working environment for its BIPOC staff, or its staff in general, they say.

“I witnessed a diverse array of exhibitions,” Marsha said, “but I think, what was a shame to me, is that it seemed to be for clout and visibility from the all-too-familiar wealthy, predominately white populations of Palo Alto, the Bay Area and North Eastern art world communities, not a genuine desire to include its workers, students or patrons of the Cantor.”

“My efforts to diversify the staff were rebuffed by the Director who labeled the candidates as unqualified,” Tokofsky wrote in the email before he left the Cantor. “I created a position for Manager of Community Partnerships and argued for reaching underserved communities, but the position was canceled and I was instructed to focus on people ‘who can pay $20 for a cocktail.’”

‘Nothing has changed’

When staff first applied to positions at the Cantor, they were met with job descriptions that presented the museum as a leader among university art institutions, with goals to reimagine “interdisciplinary cultural discourse.” Staff would be working at an inclusive institution that engages with art and artists to encourage conversations about the lived experiences of people around the world. In a summer 2019 edition of the Cantor’s magazine, Dackerman depicted a vision of “an inclusive institution that engages with art, artists, and art history to foster conversations about the world in which we live.”

“Dackerman references an innovative, diverse, 21st-century museum model that everybody agreed with, but the execution of her mission did not support staff, innovation or sustainable interventions in the name of diversity.”

Marsha

In comments to the consulting group, employees spoke of the Cantor’s potential and promise. That the Cantor has free admission and can thus afford to be more experimental, that it sits at the helm of a teaching institution, and that the institution is one of the most renowned and well-funded in the country should all lend itself to that mission of a 21st-century museum that’s the best among all universities, if not the best in the country, they wrote.

“We always thought, well, we get to work for Stanford, and this, the Cantor, really is Stanford’s gem,” Jordan said.

A University spokesperson wrote in an email to The Daily on July 17, more than a year after the consulting group’s first interventions, that “significant progress” is being made to “establish a positive, inclusive and healthy work environment that promotes respect and high performance.”

But the Cantor has continued to see much of its talent leave after only short stints at the museum.

Alex and other employees maintain that “nothing has changed” — if anything, it’s gotten worse, as staff battle the feeling that the adversarial relationship with Cantor leadership will never improve, and the perception that the University at large seems to be dragging its feet in helping them.

A previous version of this article indicated that permissions were added to the Cantor’s staff listserv after the circulation of Tokofsky’s letter in July 2020, when in fact the permissions had been added months earlier at the end of 2019 following the circulation of a different letter from another staff member alleging similar concerns. The Daily has also removed a photo of the Anderson Collection, which is adjacent to the Cantor and not apart of the Cantor itself. The Daily regrets these errors.

Contact Elena Shao at eshao98 ‘at’ stanford.edu.