Dear reader, I have come to a revelation: Children get all the best books.

And it’s not like I’m jealous — I’m not. I am ecstatic, in fact, that young readers get to go on fantastical, whimsical journeys while I’m stuck with Faulkner or Steinbeck. Who needs lions, witches or wardrobes when I could read an entire book about an old man catching a fish? But, even if I was to admit that I was bitter, I might find solace in one thing … children’s books may be rich and imaginative, but children characters, as they are often used, are kind of shallow compared to their adult counterparts. That being said, there’s one exception: Neil Gaiman’s “Coraline.”

I do not mean that we have a lack of interesting child characters — perish the thought! I simply mean that children do not often act like children; they resemble more young adults, handling situations in ways you would expect a young adult to do. The Charlie of the Chocolate Factories, the Matildas, and the Harry Potters (to some extent) seem to capture more the aesthetic of a child than the actual spirit, and this may not necessarily be a bad thing — after all, too much authenticity could easily backfire. Anybody with any babysitting experience can tell you that. But, I find it especially interesting when a story not only evades the potential pitfalls of an authentic child protagonist, but also capitalizes on their unique benefits. Yes they, like any other demographic, come with their own narrative affordances which ought to be utilized more often.

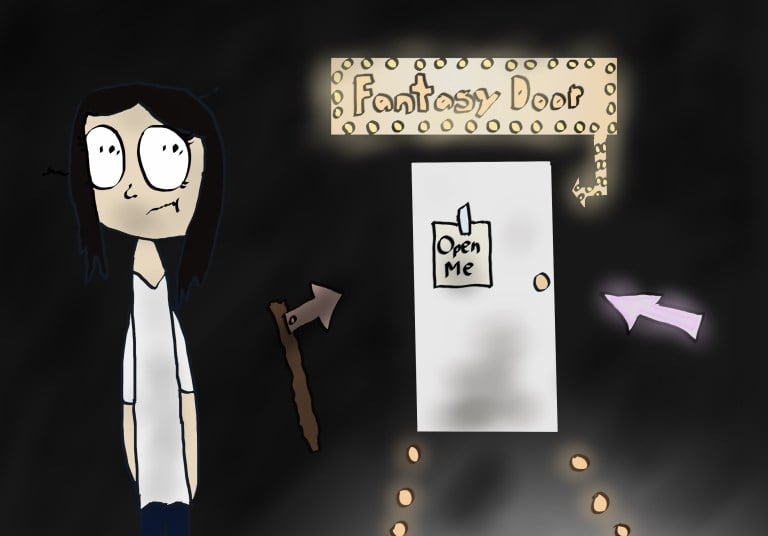

This brings us to Neil Gaiman’s “Coraline” — or as I sometimes call it, “Alice in Hot Topic.” A young girl named Coraline Jones moves into a new home surrounded by odd neighbors and busy inattentive parents. She is rather unhappy about this, and she eventually finds a door which leads to a better world, where better parents — including the seemingly perfect other mother — wait for her. But as we all know, fantasy doors are never to be trusted, and Coraline must now use her wits to escape.

It is a delightfully spooky novella perfect for an October read no matter the reader … it is also the perfect test-subject for our little narrative dissection. As the name suggests, Coraline is integral to the plot of this book, but what does her age, or her demographic, have to do with it?

For starters, let me ask a follow-up question: Why is she a child? Why couldn’t Coraline be a salary-man, or a retired grandma, or a cocker-spaniel, or an Irkan from the imperialistic planet Irk? How would this story change if Coraline was straight-up replaced with Invader Zim?

I would assume quite a bit. A salary-man would presumably be more world-weary and generally occupied, and he would approach the door in a different way. A grandma, given her position in life, might not be attracted to the same traps. A cocker-spaniel, though a good boy, is not much for social interaction and the reader would lose quite a bit of the mind-games or psychological tension. And … we’re not getting into the Irkan thing. The point is that different demographics, even the seemingly white-bread plain ones, come with different contexts that change the kind of story that is most naturally told.

Let us be clear here. There are hardly any demographics in fantasy literature as standard and stock as the little girl who has entered a fantasy door (why do they KEEP doing that?). Yet when it comes to “Coraline,” I firmly believe no other demographic would quite work, because the story itself is built around the main character being a child.

There are three unique traits of a child demographic that I believe play an integral role to “Coraline.” First, a child is curious. Second, a child is small. And third, a child can be quite annoying … this third point might not look so good out of context, but we’ll ignore that for now.

Coraline’s arguably most defining trait is curiosity, which easily fits her demographic. It does not raise any questions, for instance, when she decides to play explorer, or when she visits her neighbors out of sudden boredom. It is also this curiosity which gets her involved in the plot. She chooses to follow a pack of mice to a fantasy door, and she is curious enough to go inside of it too (the fool). The world inside is designed specifically to cater to her curiosity; while the real world was plain and disappointing, this new whimsical environment is something worth exploring, a fascinating narrative lure. Her curiosity, too, resolves the plot when Coraline challenges the villain to a scavenger hunt game. This leads not only to a seamless way of encountering various perils (and showcasing Gaiman’s fever-dream Gymboree sense of creativity) but a natural means of the main character using her unique strengths to beat a seemingly all-powerful threat. Coraline’s childlike curiosity is the oil that keeps the machine running, from beginning, middle and end.

Though if Coraline’s curiosity fuels the narrative, her smallness fuels the horror. You see, we are inherently protective over children. Even if the reader is not all that fond of the brats (their words, not mine), there is an inherent sense of uneasiness when a child is lost on a forest trail or wandering city streets alone which we would not feel so strongly with a salary-man. This uneasiness is only accentuated when our child protagonist stumbles into a completely alien environment. The suspense is amped up and the reader is able to relate these abstract, fantastical threats to real feelings and real concerns. As a good example, I would like to highlight the most abstract — and scariest — threat in the novella, however subtle it may be. Coraline is making her final escape through the doorway, but she senses something else, something “older by far than the other mother. It was deep and slow, and it knew that she was there…”. If you are wondering what this Lovecraftian abomination could be, welcome to the club — those final ellipses are the last we get of this threat. But this makes it all the scarier. This makes it beyond our comprehension. This tiny slither of story is a stand-out example of horror, and the hugeness of this mystery monster would not be so striking if our protagonist was not so inherently small.

But the heart of the journey comes from the child demographic’s third inherent trait … annoyingness. If people are butterflies, children are caterpillars, and we here at Stanford certainly have strong opinions on those. Children can be loud, they can be needy, and must they … must they be in every theater? But personal gripes aside, Gaiman takes this common viewpoint and highlights the other side, leading to a fascinating and resonant character-arc. Coraline Jones is a developing girl constantly learning about herself, making things especially difficult when she is suddenly dropped in the middle of an adult’s world. There are no other children around, her parents are too busy to cater to her specific needs, and the other neighbors are too in their own experience to relate to her. She is lonely. (Well, the movie sort of undermines this with the introduction of another child character, Wybie, but let us not get ahead of ourselves). This makes the mysterious door so alluring. The other mother addresses our main character’s loneliness and creates a world where everybody wants her around and everything revolves around her. Notice how there are still no other children meant to cater her fantasy — I believe this is because Coraline does not necessarily want like-minded company, but for her childishness (or “annoyance”) to be accepted. This represents the crux of our main character’s personal journey; to eventually reject an ideal, false fantasy and find a place in the real, faulty world she came from. It is an interesting take on the fantasy door trope, depicting and building on a common and real issue many children readers may be feeling through fantastical means, and this could not be done without a child main character. And isn’t this more interesting?

Neil Gaiman has created such a unique tale by utilizing storytelling opportunities unique to having a child as a main character; curiosity, smallness and annoyance. This is not to say, of course, that a salary-man cannot be curious, a grandmother cannot be small or a cocker-spaniel cannot be annoying. Just like real individuals, characters are not limited solely to their demographic, and things would get boring fast if they were. I am simply saying that contexts can change things in subtle, though influential, ways, and “Coraline” and Coraline exist in tandem — it cannot exist without its character.

Dear reader, in this analysis I have also only focused on age. I must wonder how other aspects of identity (gender or setting) influence this and other works as well — it is certainly enough material to fuel a totally different article. This is the exciting thing about new, exciting stories with fresh perspectives — this is the sort of fantasy door I could go inside of.

Contact Mark York at mdyorkjr ‘at’ stanford.edu.

C