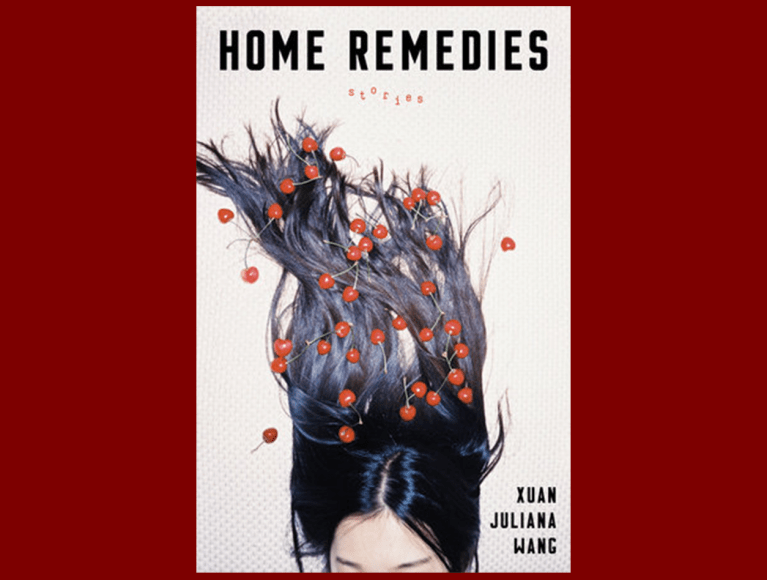

The disconnection and detachment felt by displaced Chinese is highlighted in the 12 short stories of Xuan Juliana Wang’s debut, “Home Remedies.”

Wang, who took part in the two-year Stanford’s Wallace Stegner Fellowship for writing, paints snapshots of her characters’ lives from the high-fashion streets of Paris to a lived-in warehouse in Greenpoint to the 798 art district in Beijing. The book slips in and out of its different storylines as seamlessly as a needle through gauzy fabric.

In the past couple of years, there has been an explosion of Asian, specifically Chinese, representation in Western media. As a result, the themes of alienation and floating aimlessness in “Home Remedies” aren’t new.

However, the anthological format of Wang’s book is a novel approach to the story of Chinese diaspora. Rather than tracing the path of a single family, Wang jumps from person to person and place to place, drawing sharp parallels between complete strangers. In this way, she creates a clear image of this new generation of Chinese youth: displaced and disillusioned.

Wang emphasizes the universality of these themes through a diverse cast of characters and situations. No matter who they are, what they’re doing or where they are, these Chinese youth are lost, trying to fit themselves into the cracks of a world that doesn’t want them. The awkward blend of traditional Chinese values and independent Western beliefs (a conflict especially prominent in “Algorithmic Problem-Solving for Father-Daughter Relationships,” one of the 12 stories that examines the turbulent relationship between a Chinese father and his American daughter) characterizes the struggles this new generation faces.

“Who are we?” they ask themselves.

Many of these confused youth come to their own strange conclusions. In the story “For Our Children and for Ourselves,” Xiao Gang decides that he is a man who will do anything for his happiness, for his family’s happiness, including marrying a stunted woman he has never met.

Many more of the characters don’t have an answer at all. The narrator of “Days of Being Mild” idles his time away, wishing to create meaning in his life while watching his group of artist friends splinter apart. All of these characters meander their way through life, sometimes without purpose, sometimes driven, hoping to make something out of nothing.

None of the stories feel complete on their own. Wang writes them around the pivotal moments of these characters’ lives: the moment a mother and father abandon their three children in “Mott Street in July,” the moment a tight-knit group of fuerdai (second-generation rich) choose to stand against the education their wealthy parents tried to buy for them in “Fuerdai to the Max” and the moment an Olympic hopeful gives up his career because he understands his partner will never love him back in “Vaulting the Sea.”

Wang constructs entire tales around these single snapshots, but the end of a story seems more like the beginning of a life. Perhaps because of the unfinished nature of the standalone stories, her anthology reads like a single, connected piece despite different characters, settings, points of views and tenses. We draw clearer connections between the stories because their endings are the next story’s beginning.

Though she writes in simple words, Wang is able to create strikingly poetic images. We are drawn by the crisp crunch of a qigong grandmaster who eats glass to prove himself in “White Tiger of the West,” the never-ending spin of the world on its axis when Maggie intentionally ages herself several years in the course of a few minutes in “Future Cat” and, my personal favorite, the image of Taoyu’s “elaborate wave goodbye” — his partner’s flailing body in a synchronized dive that never happens — in “Vaulting the Sea.” As varied as they may be, the clean, crisp images Wang creates are nevertheless the embodiment of the yearning for more that she explores in her anthology.

“Home Remedies” is a unique observation of what it means to be young and Chinese in the modern world. Wang’s boundless empathy and deep insight allow her to tell the narratives of a voiceless generation that is learning how to speak up.

Contact Lindsay Wang at lindsayzwang ‘at’ gmail.com.