The sold-out crowd in front of Green Library bustled with activity on July 15 as Stanford community members of different generations struck up conversation with each other, reminiscing about the times they had spent in the library and discussing how it has changed. The community was gathered to memorialize a pivotal moment in Stanford’s history— the 100th anniversary of Green Library’s opening on July 14, 1919.

Green’s physical and technological evolution over the years has positioned the library as not just a communal space for interdisciplinary scholars, but also as a trailblazer — revolutionizing the way resources are accessed and shared across the world.

Though Green now stands as the unquestioned centerpiece of the Stanford Libraries system, it didn’t start that way. Other Stanford libraries have come and gone with time, but their history — along with Jane Stanford’s vision for a “grand library”— is integral to what Green has become.

Before Green

Located in what is now Building 10 of the Main Quad, Stanford’s earliest library dates back to the University’s establishment in 1885. The original library could hold a mere 100 students and contained 3,000 books, most of which were donated by members of the Stanford family and the University’s first president, David Starr Jordan.

The number of books increased by more than 5,000 per year, quickly outgrowing the space. Stanford needed a second, larger library.

The second library — what has since become Wallenberg Hall — was built in 1900 and named after Thomas Welton Stanford, Leland Stanford’s younger brother and the primary donor toward the library’s construction.

“When [the Thomas Welton Stanford Library] opened in 1900, a volunteer group of 250 students and faculty marched the books from the inner quad to the outer quad,” Stanford archivist Daniel Hartwig told The Daily. “It took about an hour and a half, so there wasn’t a whole lot of materials to move at that time.”

But as the collection proliferated, Jane Stanford began planning for a new library in 1902. She envisioned a stand-alone library that could store a million books, foreseeing its significance as a resource and symbol for the University.

“I deeply and fully appreciate what a well-selected and sufficient library means to a university,” Jane Stanford said in a 1905 speech. “With a grand library we would be able to call to our assistance the ableist and best professors in the land, and our own honored professors could do better work.”

That same year, immediately after realizing that she had been poisoned, Jane Stanford concluded her injunctions for her trustees, with one of them being to endow all $500,000 raised by selling her jewels toward the purchase of books and other publications for the library. The resulting “Jewel Fund” was established shortly before her death on Feb. 28, 1905.

“On early books of the library, there’s a little bookplate, or an inscription in the front of the book,” said Stanford archivist Josh Schneider. “And on each of the inscriptions, there is a picture of Jane Stanford holding her jewels up to Athena, the goddess of wisdom.”

Jane Stanford’s vision, combined with the need to accommodate Stanford’s ever-growing library collection, resulted in a third, larger building that briefly stood northeast of Main Quad. But the building was not structurally sound, and San Francisco glassmaker Joseph MacKay had designed the building without consulting librarians about spatial optimization. Before it could be opened to the public, the building collapsed as a result of the 1906 San Francisco earthquake.

For a decade afterward, no significant progress was made toward designing a new library, partly due to World War I and the University’s focus on other projects.

“After the 1906 earthquake, the University officials asked Carnegie a few times for permission to build the library, and got turned down every time, so they prioritized other things,” Hartwig said. “It was only in 1916 that the formal planning started.”

Construction of Stanford’s Main Library, now known as the Bing Wing of Green, began in 1917. Its completion would finally materialize Jane Stanford’s dream.

The first 100 years

When Main Library opened in 1919, it had space for more than 700,000 books. Stanford’s acquisition of Cooper Medical College in San Francisco also brought more than 30,000 books to the Stanford library system, though they weren’t moved to Stanford’s main campus until 1959. Herbert Hoover donated his collection of more than a million historic documents as well.

In 1966, the J. Henry Meyer undergraduate library was constructed in order to expand scientific and research materials and to provide more space and facilities for undergraduate students.

The East Wing was added to Main Library in 1980, doubling its collection and floor space. The library was then renamed Green Library after the Texas Instruments founder and primary donor for the East Wing of the library, Cecil H. Green, and the original portion of the library was renamed the West Wing.

“[Green] was traveling with his family in San Francisco during the 1906 San Francisco earthquake,” Schneider said. “He credits that a lot later in life for sparking an interest in him into exploratory geophysics, and making him feel more sympathetic toward one of the earlier Stanford libraries destroyed during the earthquake.”

Nearly a decade after the construction of Green Library’s East Wing, the 1989 Loma Prieta earthquake substantially damaged Green Library’s West Wing. But the building’s early-1900s architectural style and symbolic significance were hard to imitate. With that in mind, Stanford’s then-president Gerhard Casper made the decision to reconstruct rather than demolish the original wing of the library, a process that took tens of millions of dollars and 10 years to finish.

After the construction, funded primarily by Peter and Helen Bing and finished in 1999, the West Wing was renamed the Bing Wing. The nearby Meyer Library was demolished in 2015, and books previously held at Meyer were transferred to Lathrop Library, built in Sept. 2014.

While libraries have been renamed and replaced over time, their importance to the Stanford community remains unchanged.

“Just like my journey at Stanford, my experience at the libraries has been one of interdisciplinary exploration … I believe that without these extensive resources I would not have the courage to go beyond my comfort zone and do interdisciplinary research in a number of fields,” said Sani Eskinazi ’20.

Facing forward

Though the centennial is a time to celebrate the libraries’ history, Stanford Libraries continues to look at what the next century holds. The centennial celebration’s theme, “Beyond100,” highlighted three important aspects of Stanford Libraries’ vision for the future: sparking curiosity, elevating knowledge, and transforming scholarship.

“Our libraries cross disciplines, and bring people out of their areas of focused research into shared spaces,” said Deputy Librarian Mimi Calter. “In doing so, they allow people to come together for intellectual inspiration and respite.”

With these principles in mind, Stanford Libraries is continually working on projects that allow for improved use of and access to the library and its resources. Several years ago, in order to better serve the needs of students in an increasingly research-driven environment, Stanford Libraries decided to focus its projects on three priorities: access, community, and stewardship.

Of those priorities, access is an area where Stanford Libraries has already grown immensely, according to Calter. She said Stanford Libraries has played an important role in increasing access to resources for students in institutions worldwide by creating digital formats of materials that are not only easy to use, but also convenient to find.

“I think where our reputation is made and where Stanford Libraries stands out among peer organizations is really our work on digitalization, and the efforts that we’ve made to make materials digitally accessible,” Calter said.

In fact, Stanford Libraries was a founding member of the International Image Interoperability Framework (IIIF) in collaboration with Oxford University’s Bodleian Library and the British Library. With almost 150 libraries, archives and museums in its network, IIIF gives scholars everywhere unrestricted access to images of books, maps, manuscripts, music scores, photography and art.

Stanford Libraries is also diversifying the means through which visitors can explore the knowledge stored at Green. First opened in 2016 on the fourth floor, the David Rumsey Map Center is a resource center equipped with beautiful and rare volumes, maps and atlases, touchscreen, high-resolution displays and virtual reality headsets entirely designed for an immersive learning experience.

“We’re not prioritizing one format of information over another,” said Deardra Fuzzell, a cartographic technology specialist at the David Rumsey Map Center. “It’s all about how they work together to leverage teaching, research and learning.”

Though Jane Stanford died before her vision was realized, she left a continuing legacy and inspiration to meet the future needs of scholars and to maintain the emblematic significance of a grand library.

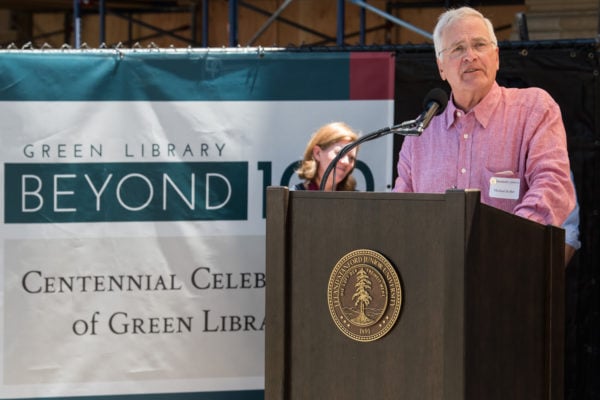

“Jane Stanford looked beyond 1919 and toward 2019, and it is our turn to look beyond 2019,” said Michael Keller, University Librarian and Vice Provost for Teaching and Learning, at the centennial event. “Given the wide range and high ambition of Stanford professors and students, anticipating their needs on a very broad band of research topics is our mantra.”

Contact Anna Chiang at annac777 ‘at’ gmail.com and Brian Lee at bl45983 ‘at’ pausd.us.