Before this week, Stanford students could view the Common Applications and high school transcripts of other students if they first requested to view their own admission documents under the Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act (FERPA).

Accessible documents contained sensitive personal information including, for some students, Social Security numbers. Other obtainable data included students’ ethnicity, legacy status, home address, citizenship status, criminal status, standardized test scores, personal essays and whether they applied for financial aid. Official standardized test score reports were also accessible.

Students’ documents were not searchable by name, but were instead made accessible by changing a numeric ID in a URL.

A Stanford student who recently submitted a FERPA request for their admissions documents discovered the vulnerability in a third-party content management system called NolijWeb that the University has used since 2009 to host scanned files. Since 2015, students who have submitted FERPA requests have been able to view files through NolijWeb.

Between Jan. 28 and 29, the student briefly accessed 81 students’ records while attempting to assess the scope of the vulnerability. Others informed of the issue accessed information contained in 12 students’ records during that time period while seeking to learn more about the kinds of files exposed. University spokesperson Brad Hayward said the University has not identified other “instances of unauthorized viewing” but is still reviewing the matter.

The Daily withheld reporting on the exposed data until the University could secure the breach so that students’ records could be protected. The student who disclosed the breach to The Daily was granted anonymity to protect them from potential legal repercussions for accessing private information while investigating the security flaw.

Stanford will notify the 93 students whose privacy was compromised because of this flaw.

“We regret this vulnerability in our system and apologize to those whose records were inappropriately viewed,” Hayward wrote in an email to The Daily. “We have worked to remedy the situation as quickly as possible and will continue working to better protect our systems and data.”

Stanford has also notified Nolij’s parent company Hyland Software of the vulnerability. Hyland acquired Nolij in 2017 and announced on Dec. 31, 2017 that it would be discontinuing the NolijWeb product. While Stanford University Information Technology (UIT) intends to finish implementing a new platform to replace the NolijWeb system by this summer, a number of schools still use NolijWeb to store admissions records. It is unclear how many schools using NolijWeb give students access to the online documents, or how many might be subject to the vulnerability.

The Daily reached out to eight different executives at Hyland Software for comment and expressed concern that other schools’ data may be similarly compromised by NolijWeb. Alexa Marinos, Hyland’s Senior Manager of Corporate Communications, confirmed receiving The Daily’s phone and email requests for comment, made over the course of a week. However, the company provided no statement on the matter.

Accessing admissions records

FERPA, a U.S. federal law, provides to parents specific protections related to their children’s education records, including academic transcripts and family contact information. Students who are at least 18 years old or enrolled in postsecondary education may request their own education records under the law.

FERPA gained recognition among Stanford students in January 2015 after the Fountain Hopper (FoHo), a widely-circulated campus email newsletter, reported that FERPA requests allow students to see their Stanford application materials, including the numerical scores assigned to them by admissions officers. Officers were found to rate applicants on a scale of one to five on various metrics including testing, personal qualities and interviews. Legacy status, ethnicity and 300-word summaries written by Stanford admissions counselors distilling their perception of the candidate were all available. Any student who requested their application materials would receive printed copies of their admissions documents, stored on NolijWeb.

Deluged with FERPA requests after the FoHo’s report, Stanford and other universities soon began erasing records of admissions officers’ ratings and comments on student applications once students arrive on campus. At this point, Stanford began to give students direct access to NolijWeb to expedite access to their own records. Occasionally, a delay involved in destroying the records still allows first-year students to view such comments on their admissions records, multiple current freshmen found.

The vulnerability, explained

Students whose FERPA requests are approved by the University are directed toward a link titled “Student Admission Documents” on Axess, Stanford’s information portal for students, faculty and staff. That link directs them to NolijWeb where — after entering their SUNet IDs into a search box — students can view their own scanned documents.

When a user views one of their files, the browser performs a network request. However, a student may use tools like Google Chrome’s “Inspect Element” — commonly used by programmers to debug websites — to view that network request’s URL and modify it to give them access to another student’s files.

While using file identifications in such a URL is not uncommon, sites typically add protections to prevent people from accessing files not intended for them.

Because URLs and files are linked through numeric IDs, the NolijWeb vulnerability did not allow students to retrieve documents by name nor by any other identifying information. Instead, incrementing file ID numbers in URLs allowed access to arbitrary students’ files. But a web scraper could theoretically help someone download all available documents, the student who discovered the vulnerability said.

The student was especially concerned that their Social Security number was visible on one of their documents.

“It wasn’t anything sophisticated,” the student said of their methods, adding that anyone with web development experience could have exploited the vulnerability with ease. “You change the ID slightly and it just gives you someone else’s records.”

Stanford’s response

Since learning of the vulnerability, UIT has disabled the component of NolijWeb that allowed students to access others’ records. In the meantime, the University has suspended online access to FERPA documents while it researches short-term alternatives.

UIT has also maintained logs of unauthorized access to students’ files since the issue was brought to their attention, and Hayward said “a thorough review is currently underway.”

Though Stanford has used NolijWeb for 10 years and students have had direct access since 2015, the University does not know how long the vulnerability has existed.

“Exploiting this vulnerability requires an authenticated student login and specific knowledge of the application’s underlying behavior,” Hayward wrote. “We believe this to be the first report of the issue.”

Because of the necessity of an authenticated student login, the vulnerability was not detected by UIT’s regular audits of its third-party software, Hayward said.

He noted that the vulnerability did not allow students to access other documents stored in NolijWeb besides the admissions files of undergraduates. But students who have graduated since 2015 may have had their files exposed, he added.

Cybersecurity issues at Stanford

“Stanford’s Information Security Office is continually looking for opportunities to bolster the overall security posture of our systems,” Hayward wrote.

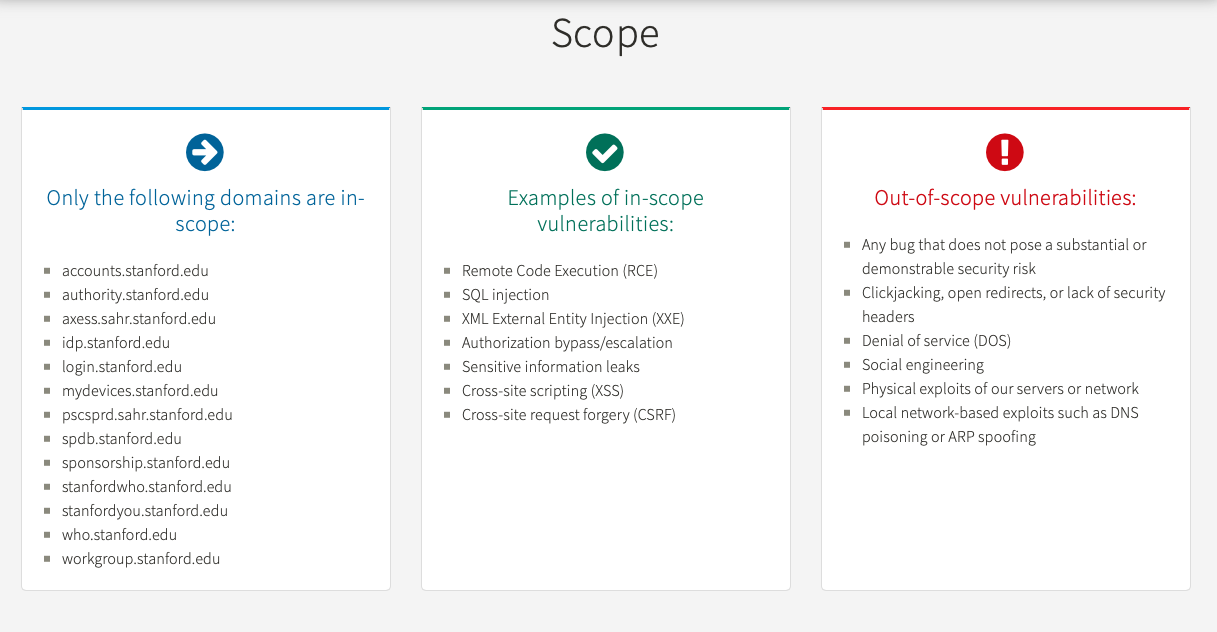

One such effort was the recent launch of Stanford’s Bug Bounty Program, meant to encourage community members to notify the University of vulnerabilities in its web systems. However, the FERPA records exposure would not qualify for the program; the web domain affected is not among those listed as eligible for a bounty.

“As this is an experimental program, we wanted to begin with a very limited set of systems to gauge the response,” Hayward wrote. “If the program goes well, we intend to gradually expand the scope over time.”

If within the initiative’s scope, a vulnerability that results in the “exposure of sensitive information” is eligible for a reward of $150 to $450. Since learning of the NolijWeb data breach, Stanford has amended the Bug Bounty Program to explicitly include safe harbor provisions for discovery of out-of-scope vulnerabilities that are “responsibly report[ed].”

The program’s terms specify that participants must not access confidential information beyond what is absolutely necessary to demonstrate the vulnerability.

As of Monday, UIT had received 43 submissions to the Bug Bounty program “of varying severity levels,” Hayward wrote. Stanford intends to publish “high-level information about the bugs, but not the details,” on the program’s website.

“Even after a fix is implemented, publicly disclosing a vulnerability still has security implications,” Hayward wrote.

Prior to the establishment of the Bug Bounty program, multiple other cybersecurity issues at Stanford resulted in leaks of Stanford affiliates’ data.

In late 2017, The Daily discovered permissions errors in a University-wide file-sharing system called the Andrew File System (AFS) that allowed any Stanford community members — as well as AFS users from other schools — to access information on sexual assault cases prepared from campus therapy sessions, emails about student conduct issues and other confidential information.

A month later, Stanford reported that the names, birthdays, salaries and social security numbers of 10,000 University staff members working in 2008 had been exposed on a shared Graduate School of Business (GSB) site between September 2016 and March 2017. The information was also accidentally made public due to permissions errors. Shortly after the leak’s reveal, GSB Associate Dean and Chief Digital Officer Ranga Jayaraman announced he would leave his job.

The student who found the FERPA vulnerability said the recent succession of data breaches at Stanford is concerning.

“I think it’s kind of ironic that Stanford is one of the best CS schools in the country, but it’s so negligent in terms of these kinds of important records,” they said.

Contact Julia Ingram at jmingram ‘at’ stanford.edu and Hannah Knowles at hknowles ‘at’ stanford.edu.