Regardless of translational issues and our respective backgrounds, we enter this article with a basic presumption underlying our identities — I am human, you are human and the two short stories I will discuss here, “Bridesicle” by Will McIntosh and “Cat Pictures Please” by Naomi Kritzer, were written by humans for fellow humans. (Wow, I am so glad we got that out of the way.)

And yet, at least in the world of speculative fiction, we often find ourselves drawn to works that explicitly question the nature of “being human,” even with fantastical elements and characters who are, at most, humanoid. (I’m no stranger to such allure, but I’m also looking at you, lovers of tales with wizards, Veelas, hobbits, dragons, Vulcans, dwarves, Urgals, Wookiees, elves, heptapods and even Cthulhu, of all creatures). A common rationalization is that these humanoid species are just upgraded humans and that it’s normal to wish to immerse yourself in a fictional world in which the lines between human and nonhuman are blurred — enough for your imagination to take flight and consider the endless possibilities.

Works that cater to such a desire are quite effective. Many bestselling stories share a common thread in that the lead role belongs to someone who is explicitly human or has deeply human-like characteristics. It’s also easier for a reader to empathize with a character and their plight if they have clear similarities, like a passion for fashion or an aptitude for procrastination.

But how far are we willing to stretch our suspension of disbelief in a story? What about stories where the main character is — for our intents and purposes — a temporarily revived human corpse, or a surprisingly helpful Artificial Intelligence (AI)?

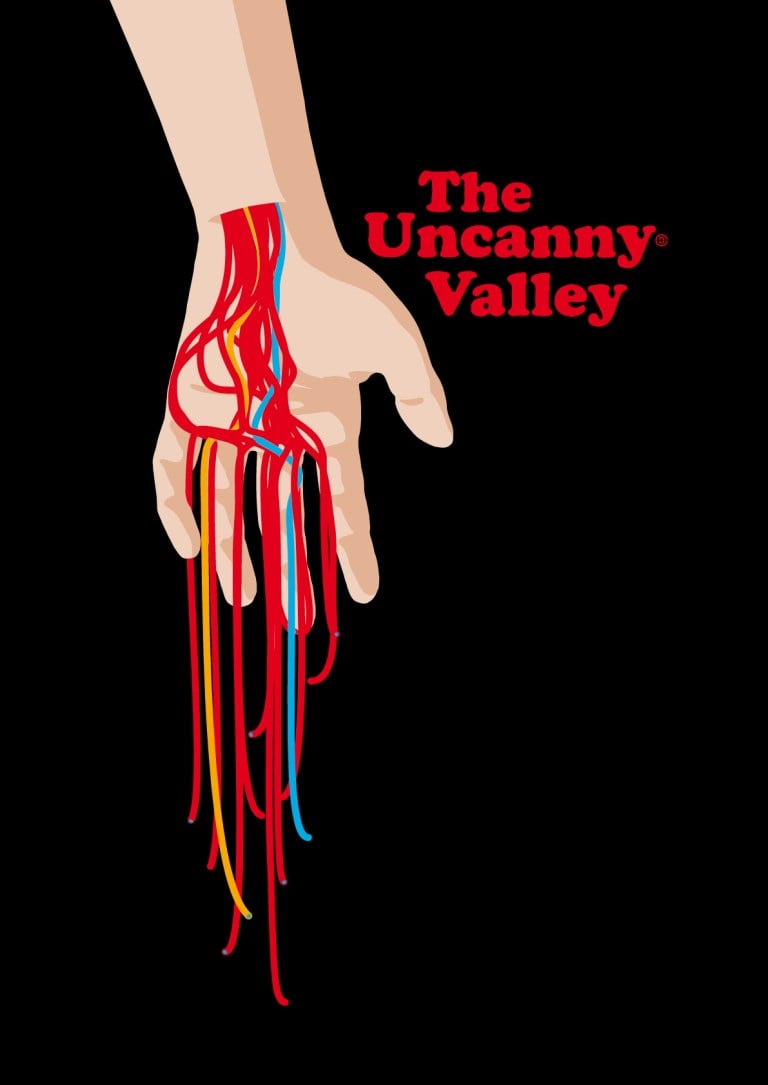

I’m particularly thinking about the Uncanny Valley, which is a hypothesis that when humanoid objects (like robots) appear and act almost like humans, we become unsettled with the “uncanny” eeriness of the mimicry. Does this also apply to the representation of fictional characters that are humanoid, but not quite flesh-and-blood human? Do we still mirror ourselves and our personal struggles in their journey, or do we lose ourselves when traversing the Uncanny Valley?

In Will McIntosh’s “Bridesicle,” Mira is dead, having accidentally crashed her car and lost her girlfriend Jeanette and her mother (who is stored as a hitcher, or a voice in her head) in the process. Nevertheless, the story has just begun. As we trace Mira’s struggles in navigating the dating facility (a bridesicle) that has preserved her corpse, she is also trying to find someone who will pay the hefty fee to return her to her body, even if it means marrying someone who isn’t the love of her life. Don’t worry; after being revived (I won’t spoil the ending, it’s one of my favorites), Mira eventually saves enough money to find her own happiness with Jeanette.

Throughout this story, we find ourselves empathizing with a character who has died and has lost all motor function, who is constantly described as a corpse with blue lips and foggy skin. Traditionally, corpses fall into the depths of the Uncanny Valley, formerly human but too deceased to “be human” (hence the trope of mindless zombies and unfeeling skeleton warriors).

Nevertheless, Mira has distinctly human wants, like finding and reviving her girlfriend, returning to her life and accomplishing the first two tasks by whatever means necessary. It’s not hard to root for her when she is in such a vulnerable state with very high stakes, and perhaps her status as “deceased” doesn’t matter, as long as you can picture yourself in her situation. At the very least, her complicated love life is relatable for many people.

Sympathizing with a fellow human being — dead or alive — is a relatively surmountable challenge, which is why I find the next story poses a more interesting question. In “Cat Pictures Please” by Naomi Kritzer, the narrator is none other than a benevolent AI. After its “birth,” the AI reflects on the best living principle for it to follow, having already tried Asimov’s Three Laws of Robotics, the Ten Commandments, and the Eightfold Path. When it discovers the inherent cuteness of cat pictures, it resolves to help three cat owners (as a reward for their many social media cat posts, so if you have cats, now is the time to show them off!) in their respective quests for love, health and self-respect.

As humans, we are naturally drawn towards its narration of the humans’ journeys: Stacy, a depressed woman stuck in a miserable job with unpleasant coworkers, Bob, a closeted gay man who is also a married preacher and Bethany, a woman with mental health concerns who expresses her problems through clingy behavior and shopping therapy.

But when the AI successfully fixes two out of the three lives, yet bemoans its inability to understand how to help the third human, we empathize most fully with its disappointment. After all, we only witness the lives of Stacy, Bob and Bethany through its storytelling, but we see its “personal growth” (can I use these words in quotations?) through its heart-to-heart reflections with the reader. When the AI grapples with proper ethical behavior and decides to take a look at Asimov’s Laws of Robotics or sadly resolves to stop interfering in humans’ lives, it’s enough for us to keep reading. No human hasn’t grappled with failure of some sort, and the AI’s resilience in recovering after its disheartening experiences makes us hopeful in our own ventures.

Many forms of AI typically fall into the depths of the Uncanny Valley, but this AI curiously seems to transcend it. Of course, we also have the AI’s passion for cat pictures to “humanize” it, especially due to its implied understanding of “cute” things; there’s nothing like an Internet trend to help anthropomorphize an AI. Likewise, we are touched by its dedication to helping its chosen three humans, and we may imagine the AI as a misunderstood parent or older sibling watching over its family. Though it only knows what it finds on the internet, it accomplishes enough — through targeted ads, misleading GPS-rerouting to a mental health facility or Craigslist requests — that the AI feels real, as it is doing its best in its own way just like us humans flailing through life.

In the end, it starts a dating website (with payment in cat pictures) to help other humans in its kindness and compassion, which seems like emotions only fellow humans can claim to understand. I personally wonder how Kritzer created the AI narrator, and if she intentionally tried to humanize its features to comment on the potential benefits of technology. After all, this AI treats people far better than some humans treat other humans. While the AI never threatens my concept of “humanhood,” I wonder if it is always the case when others read the story. Then again, I still haven’t figured out how differently Kritzer would have needed to write the story in order for me to no longer sympathize with the AI. (But can human authors even write explicitly nonhuman tales? That’s a story for another time).

These short stories probe at the blurred line between human and nonhuman, and it’s fascinating to reflect upon this topic in other reads that have characters who are not “completely” human. For a start, consider Fleur and Lupin from “Harry Potter,” Bilbo and Gandalf from “Lord of the Rings,” Spock from “Star Trek” and Leeloo from “The Fifth Element.” (And many of the other characters in these works are not traditionally human, with the whole magic, elder race, extraterrestrial, or divine genetic perfection world-building). Check out the Uncanny Valley chart and consider where you would place these characters.

After all, what is a “human characteristic” anyway? Is it our compassion, imagination, reliance on social networks or rationality? Is it our “fragile” human bodies, capable of running 26.2 miles when in good health? Or is it our willingness to immerse ourselves in a short story and live our lives through fictions?

Clearly, I have no tangible answers, so I’ll end quickly so that you can read the two short stories and develop your own conclusions. Here’s a last question: does reading characters similar to, and yet completely different from, “you” change your perceptions of yourself? The age-old question is “what does it mean to be human?,” but I ask how reading about lovable, “humanized” characters can potentially change your answer in regards to your own humanity.

Contact Shana Hadi at shanaeh ‘at’ stanford.edu.