This article is the first in a five-part Music beat series for our candidates for Album of the Year. While these albums span a wide range of musical and stylistic territory, they all deeply affected at least one of our writers.

We’re starting off our accounting of the year in (exceptional) music with two intensely personal narratives from the West Coast — Los Angeles rapper Kendrick Lamar’s breathtaking self-atomization on “DAMN.” and Pacific Northwest singer-songwriter Phil Elverum’s confrontation with grief on Mount Eerie’s “A Crow Looked at Me.”

Kendrick Lamar, “DAMN.” — Jacob Kuppermann, Desk Editor

On first glance, “DAMN.” seems to be Kendrick Lamar’s least ambitious album since “Section.80,” his 2010 debut. Unlike 2012’s “Good Kid, m.A.A.d City” and 2015’s “To Pimp A Butterfly,” which are both widely considered to be modern masterpieces of musical storytelling, “DAMN.” doesn’t have an overarching narrative, or at least not a particularly obvious one. There are repeated audio samples and themes, but no leitmotif as consistent or meaningful as the voicemails on “Good Kid, m.A.A.d City” or the poem that he recited at the end of many of the tracks on “To Pimp a Butterfly.” Where those two albums telegraphed their stories fairly obviously, “DAMN.” leaves a lot unsaid.

In that way, it’s really Kendrick’s most ambitious undertaking — an album that doesn’t tell its listeners what to think about as they listen to it. Kendrick’s first two albums rewarded relistening for all of the additional depth their stories gave you when you really paid attention to the motifs and individual narrative details. “DAMN.” instead opens up entirely new interpretations with every playthrough.

If “Good Kid, m.A.A.d City” was a beautifully rendered slice of life story and “To Pimp A Butterfly” a grand statement of political art, “DAMN.” is instead a postmodern short story collection, an avant-garde work that works as both an album and as a guide to its own listening. The final track, “DUCKWORTH.” segues into a sped-up, reversed version of the album, ending with the first line of the album’s first track, “BLOOD.” In “DAMN.”’s very structure, then, is the hint that its true meaning requires you to listen to it more than once.

All this heady conceptual material, though, would be a waste if its star weren’t so radiant. No matter how much any critic praises Kendrick’s grand narratives, his music ultimately succeeds on the sheer juggernaut-like strength of his rapping. That Kendrick Lamar is good at rapping is not a particularly profound observation — an anthology’s worth of writing has been expended for the cause of talking about Kendrick Lamar’s skill at rapping, of the way he bends syllables and pronunciations to flow effortlessly over beats as disparate as “m.A.A.d City” and “For Free?” and of the intensely layered metaphors and webs of symbolism he seems to craft on the fly with a deftness that most rappers could spend an entire career trying, and failing, to attain.

Yet on “DAMN.” he reaches new heights, whether he’s telling stories on tracks like “FEAR.” or boasting on “DNA.” or “HUMBLE.” or turning contemplative on “LOVE.” or “PRIDE.” Lesser rappers than Kendrick have tried to span such a stylistic range before, yet few have achieved the success Kendrick has. No matter what he’s rapping over, he’s the unquestioned master of the proceedings. “DAMN.” is an artistic statement that can hold its own, even in the context of Kendrick Lamar’s already masterful oeuvre.

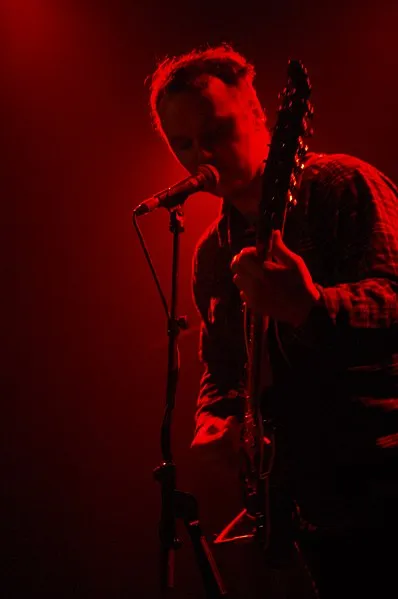

Mount Eerie, “A Crow Looked at Me” — Jacob Nierenberg, Staff Writer

When you die / you wake up / from the dream / that’s your life

Thing is, that dream goes on even if you’re not a part of it. When you leave that dream, you leave people behind, and they’re left to make sense of that dream after you’re gone. Your life ends, but its mark on the lives of others does not.

Those italicized words are from Joanne Kyger’s poem “Night Palace,” which appears on the cover of “A Crow Looked at Me,” Phil Elverum’s latest album as Mount Eerie. In a cruel twist of fate, Kyger died of cancer two days before the album was released, at the age of 82. “A Crow Looked at Me” is about Elverum’s wife, Geneviève, who was only 35 when cancer claimed her, leaving behind a daughter who will never know her and a husband tasked with preserving her memory.

There have been a lot of albums about death that have been released since I started college — hell, I even have a theory that David Bowie’s “Blackstar,” Nick Cave’s “Skeleton Tree” and Leonard Cohen’s “You Want It Darker” form a musical Deathly Hallows for 2016 — but “A Crow Looked at Me” is the most visceral album of them all. Elverum wrote and recorded these songs in the room where his wife died, and he sings and plays his guitar in hushed tones, careful not to wake his sleeping daughter in the next room over. Across the record, Elverum’s suffering is palpable and inescapable. A sunset and waves on the sea make Elverum wonder what’s become of Geneviève’s scattered ashes; a forest fire symbolizes emotional devastation; ravens and crows, two black shadows of birds, are omens of death. Elsewhere, everyday activities, such as going to the grocery store, taking out the trash and checking the mail, serve as little reminders of crushing loss. Elverum’s lyrics have always explored the space between metaphor and mundanity, but here, everything points to real death.

I’ve listened to “A Crow Looked at Me” once, and frankly, that’s as many times as I hope to hear it. A month before this album came out, someone very close to me died — a woman whom I’ve known since before I was able to form memories. I listened to this album in front of her mobile home, and it was like losing her all over again. I won’t listen to this album again until the next time I lose someone close to me, and it’ll hurt like an exorcism. I can’t listen to it any other way.

Love is a tether that binds us to others. When that tether breaks, two things happen. First comes the shock when that tether snaps back, hitting us in the chest. That’s the immediate pain of loss, but what comes afterward is far more complicated. We are left to hold that tether, feeling its dead weight, knowing that there is no one holding it on the other end. “A Crow Looked at Me” is the sound of grieving. It’s the sound of Elverum carrying that tether — feeling his wife’s presence on the other end weaken, flailing it at the heavens in anguish and vowing to hold onto it until he meets Geneviève again, in whatever afterlife lies beyond our dreams.

Contact Jacob Kuppermann at jkupperm ‘at’ stanford.edu and Jacob Nierenberg at jhn2017 ‘at’ stanford.edu.