Secretary of Education Betsy DeVos’ decision to reevaluate federal guidance governing the Title IX process for adjudicating sexual assault cases on college campuses was the latest in a series of developments that have made sexual assault one of the most high profile issues on campus. The issues of how to reduce sexual assault, respond to accusations and support survivors of sexual assault have sparked large student demonstrations and Stanford policy changes in recent years.

Here, The Daily explains Title IX and gives a condensed overview of how the contentious issue has evolved on campus.

Policy in flux

Title IX is a federal law enacted in 1972 that prohibits educational institutions that receive federal funding, like Stanford, from excluding, discriminating against or denying the benefits of an educational program on the basis of sex.

In 2011, the Department of Education, which monitors compliance with the law, issued a “Dear Colleague” letter that told colleges and universities that sexual harassment and sexual violence are forms of sex-based discrimination. The letter further stated that institutions of higher learning have a corresponding obligation to investigate complaints of sexual harassment and violence on their campuses and take appropriate steps to prevent them from recurring. This meant that institutions are required to have a process in place to investigate and judge complaints of sexual assault parallel to and separate from any criminal investigation and prosecution that might be conducted by law enforcement.

What that investigation and disciplinary process should be at Stanford has been the subject of repeated changes and much scrutiny.

Between 1996 and 2009, there were 104 reports of sexual assault at Stanford, which resulted in three disciplinary hearings under the adjudication system in place at the time. In April 2010, Stanford established the “Alternate Review Process,” which replaced the old process as the University’s means of examining sexual assault complaints and determining sanctions.

Under the Alternate Review Process, accusations of sexual assault were judged by a five-member panel, which consisted of three students and two faculty or staff members. At the same time, Stanford reduced the burden of proof required to find someone responsible for a charge from “beyond a reasonable doubt” to a “preponderance of evidence” standard. Under the new standard, which was mandated by the Department of Education’s 2011 “Dear Colleague” letter, a panel would only need to be convinced that the offense had been more likely than not committed.

ARP replaced

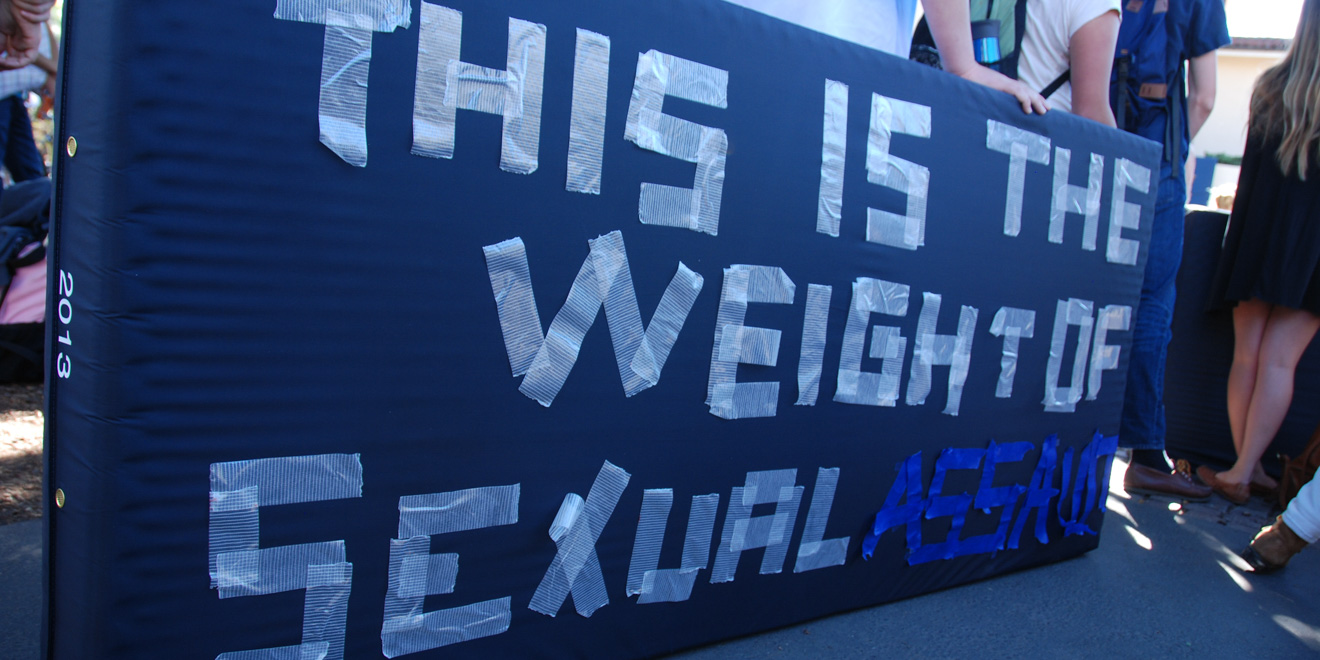

Despite these changes, Stanford’s policy for handling sexual assault cases came under intense criticism during spring quarter 2014. Leah Francis ’14, a student and survivor of sexual assault, circulated a letter around the Stanford community that called for a demonstration against the University’s process for adjudicating sexual assault cases.

After Francis reported to the University that she had been sexually assaulted by another student, a panel found the accused in Francis’ case responsible. The panel gave the male student a one year suspension, allowing him to graduate on time and return to graduate school at Stanford a year later — a punishment Francis derided as “gap year.” Francis’ case also took nearly five months to process, while the Department of Education indicated that a typical case should take around 60 days.

Francis called for Stanford to expand resources for sexual assault survivors and make expulsion a mandatory sanction for sexual assault. Several hundred students showed up to a rally several days later in the first in a series of demonstrations.

In 2016, Stanford began using a new process for handling sexual assault complaints, run by the Title IX office, that remains in place today.

Once the Title IX office receives a complaint, it investigates it to determine if there is enough evidence to charge the alleged assailant. Although some University employees are required to forward complaints they receive to the Title IX office, some resources such as the Confidential Support Team, Counseling and Psychological Services and clergy are confidential and are not required to forward complaints.

If the Title IX Coordinator believes that a panel could find a student responsible for prohibited conduct, but there is no significant disagreement between the defendant, complainant and Title IX office regarding what happened and what the penalty should be, the complainant can elect to skip a hearing. If the Title IX office deems evidence sufficient to charge, the complainant can also choose to have a hearing before a three-person panel. The panel is appointed from a pool of faculty, staff and graduate students selected for that purpose. A unanimous ruling is required to find an alleged assailant responsible.

Expulsion is currently the default, but not mandatory, sanction for sexual assault, defined by Stanford as oral or penetrative sex carried out by force or incapacitation. Other sexual offenses can carry a wide range of penalties.

Stanford’s reforms to the Title IX process came under almost immediate criticism. Advocates for a more aggressive reform package argued that Stanford had an unusually narrow definition of sexual assault and that requiring a unanimous vote for a finding of responsibility set Stanford apart from other schools and would cause more accused students to be acquitted. Unlike many peer institutions, Stanford does not count the unwanted touching of an intimate body part as a form of sexual assault, instead classifying it in the broader category of “sexual misconduct.”

As of earlier this year, Stanford was one of only four schools in the U.S. News top 20 colleges or schools in the Pac-12 to require a unanimous vote to reach a responsible finding. Two of those four schools use two-member panels, meaning that a majority decision will necessarily be unanimous.

Explaining Stanford’s policy, administrators have said that Stanford mirrors California legal definitions and that Stanford separates types of sexual offenses in order to differentiate default sanctions. A task force on sexual assault is currently reviewing the University’s policies and still accepting community input.

Although students are not represented in Title IX hearings by lawyers, both the complainant and respondent in cases have access to up to nine hours of free legal assistance by a lawyer from a pool the Title IX office created for that purpose — a resource rare among colleges. However, some allege that nine hours of legal assistance is inadequate to properly support students involved in the Title IX process.

Stanford was accused of retaliation in February when it dropped one of the attorneys retained for advising students in the Title IX process, Crystal Riggins, after she made critical comments about Stanford’s Title IX process to The New York Times. The Stanford administrator who wrote to Riggins with news of her dismissal said Riggins’ public statements were “disappointing” and indicated a lack of confidence in Stanford’s Title IX process.

Increasing attention to the incident, Riggins was at the time the only member of the pool of attorneys the University keeps on retainer for Title IX cases who specialized in representing sexual assault complainants at Stanford.

Accusations of overreach

Although some students and faculty have accused Stanford of an inadequately aggressive approach to Title IX cases, others have accused Stanford’s Title IX office of violating the rights of respondents and overreaching in its investigation of student groups.

The male student who Stanford found responsible for assaulting Francis filed a lawsuit against the University in 2016, alleging that Stanford’s process violated various due process rights and discriminated against him. Other defense lawyers have also criticized the Title IX process, alleging that Stanford provides so little information to respondents that it is difficult to prepare an effective defense. One attorney told The Daily previously that a defendant he represented asked Stanford to disclose which calendar year an alleged assault took place in but had the request rejected.

Even more controversial have been Title IX cases against the fraternity Sigma Alpha Epsilon (SAE) and the Stanford Band.

Accused of creating a “sexually hostile environment” during a 2014 toga party and of subsequently retaliating against witnesses, SAE lost its status as a housed fraternity and was placed on three years of probation in 2015. Some SAE members criticized the Title IX investigation for alleged procedural failures, while a student subject to an anonymous Whatsgoodly poll attacking her character for allegedly reporting SAE’s party accused SAE of retaliation. The individual SAE member accused of directly retaliating against the suspected witness was acquitted of retaliation in an Office of Community Standards disciplinary hearing, while SAE was found responsible for the same charge in the Title IX process.

Following allegations of sexual harassment and hazing during the 2011-12 school years, a Title IX investigation found the Leland Stanford Junior Marching Band responsible for these accusations and imposed a one-year travel and alcohol ban in 2015. After alleged violations of the no-travel and alcohol policies, Stanford suspended the Band in December 2016 — a move that drew swift outcry from many students and alumni — until the Band successfully appealed the suspension in January.

Brock Turner

As debates about the future of Stanford’s Title IX process continue, one of the most high profile developments in sexual assault issues at Stanford has little direct connection to Title IX.

On Jan. 18, 2015, Stanford student and athlete Brock Turner sexually assaulted an unconscious woman outside Kappa Alpha on the Stanford campus and was arrested for the crime. Unlike in most alleged sexual assaults at Stanford, Turner was subsequently charged and convicted of rape in a Santa Clara County court. Turner’s case drew international media attention after the survivor of the assault read a moving statement in court on the impact of the assault; scrutiny grew after presiding judge, Aaron Persky ’84 MA ’85, then sentenced Turner to six months in jail and three years of probation.

What many criticized as a lenient sentence sparked public outrage and led a Stanford Law School professor to lead a petition to force a recall election against Persky. Meanwhile, legislators changed California state law to stiffen rape penalties in cases where the victim is unconscious.

The recall petition is currently entangled in litigation over procedural questions, and Persky has stepped up his efforts to fight the recall, garnering support from a number of the recall leader’s colleagues at Stanford Law School, among others. But recall supporters are still hoping to get adequate signatures by early January so that the recall election can take place during California’s 2018 primary elections.

Contact Caleb Smith at caleb17 ‘at’ stanford.edu.