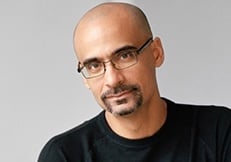

Renowned author Junot Díaz, creative writing professor at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), visited Stanford this week. Born in Santo Domingo, Díaz moved to central New Jersey at the age of six; much of his work draws on the immigrant experience. His debut novel, “The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao,” which received the Pulitzer Prize in 2008, tells the story of a Dominican-American science fiction aficionado who struggles with fitting into the macho culture around him. The Daily interviewed Díaz over the phone shortly before his visit to Stanford.

The Stanford Daily (TSD): In an essay in Oprah Magazine, you talked about your journey as a writer — specifically how you spent five years working on a manuscript that you did not like, almost gave up and then spent another two years toiling over it. At what point did you realize that… you were satisfied with the words on the page?

Junot Díaz (JD): Your instincts just sharpen. My instincts are much sharper now than when I was 19. You become more aware of what is required to complete a story. This instinct is a combo of training, your reading and introspection — introspection where you [ask], “How much do you think about the material? How much are you reading?” Artists have always had to make these kind of decisions, ask these kind of questions.

TSD: Your novel, “The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao,” interweaves themes of science fiction and fantasy. Why did you add these themes, and in what way do you think that they enhanced the overall story?

JD: I grew up with this body of literature [of science fiction and fantasy]; I was a veteran reader of these genres. Given the fact that Afro-Caribbean experience is so extreme, extreme narratives can help in some ways to communicate and in some ways explain this extreme reality.

TSD: Can you clarify what you mean by the extreme Afro-Caribbean experience?

JD: To be from the community that I come from. I come from a history of slavery and genocide, histories that are nearly impossible for minds raised with bourgeois realism to grasp. My community’s history, in many ways, shatters what [these minds] know.

TSD: Immigration and identity are big juggernauts in your writing, and these themes have really come to prominence in the wake of current events in the U.S. Are you taking these experiences and morphing them in your writing?

JD: Right now, I’m not writing anything, [but] I’m deeply engaged in our politics. [It’s] been a big part of my life to be a part of certain kinds of activism. I am an enemy of white supremacy, and enemies of white supremacy will find themselves called by these very troubled times. Let’s see what the future shows. Right now, I’m not working on anything, and whether or not [current events] go into my writing, I’m not sure.

TSD: Stanford has a large population of young aspiring writers. What advice would you give to them?

JD: Young writers are inundated with advice, so the question I always ask is, “Do young writers need any more advice?” When I meet other artists, my basic tack with them is to bring positivity and encouragement and try to keep advice to the minimum, because how much more could they get? Sometimes [your writing] pans out, and sometimes it doesn’t, but it’s the journey that makes a great learning experience.

TSD: What do you do when your writing doesn’t pan out?

JD: To be honest, these days, if things don’t work out, I’ll put it aside and try to read for a couple of months. When I was younger, I was more distressed about it, distressed when [writing] didn’t work. Fortunately, in my life, I have things more important than writing — you know, I love to read and be engaged in community activism and academics and intellectual life a lot more.

TSD: What are you reading these days?

JD: Well, I just got done judging for the Pulitzer, so everything I read are the very things I can’t talk about. But the rest is just, unfortunately, boring old man shit, just stuff from my university [that’s] taking most of my energy. But what have I read recently that I liked was Colson Whitehead’s book, “The Underground Railroad.” It also won the Pulitzer and I enjoyed that quite a lot.

TSD: Have you ever found genres to be limiting constructs to writing?

JD: I think that’s the nature of genre, you know. It’s a voluntary set of limitations [and] those limitations help you do things that you otherwise wouldn’t have been able to do. If you just stick to the rules of genres, sure, it’ll be familiar and easy, but on the other hand, if you use those restrictions creatively, you can think of something new.

TSD: Can you give an example of a limitation?

JD: Well, this is something I gave to my students [at MIT]. In general, if [you] give a story that can only have a dog and an iceberg, you’ll have a lot of bad stories. But, you’ll have some stories that brilliantly deal with these obstacles. Some of these students make great wild fucking shit.

TSD: What’s an example of a book that worked well with set limitations?

JD: “Watership Down” seems like a weird book about rabbits. But, when you look at it, it creates a wonderful narrative. [The writer is] dwelling on the things which, in some ways, speak highly to rabbits, so what would that be? Being tricksters, being excellent beings. There are things to us that wouldn’t work, but for rabbits, it can become metaphorically powerful and that’s an outcome of not being able — or not wanting to — break from a rabbit’s personality. I think “Watership Down” is an excellent example of a book where a writer created a bunch of constraints, created a bunch of limitations. [The writer said], you know, I’m going to write a book about rabbits and I’m going to create an epic out of it, and I think that the book itself is a response to those limitations. You know, the book is quite wonderful.

This transcript has been lightly edited and condensed.

Contact Aparna Verma at averma2 ‘at’ stanford.edu.