We live in interesting times. With the election of Donald Trump, the advent of Brexit and the normalization of right-wing populists and demagogues across Europe, the world we live in seems to many to be far more uncertain, dangerous and oppressive than it has been in the past few decades. While groups throughout the country have been organizing to resist this rising tide and protect those most at risk, others have taken a more optimistic tact. They look into the abyss of reactionary politics and far-right governance and see opportunity — more specifically, the opportunity for a creative renaissance.

The most notable figure to make this claim is singer and performance artist Amanda Palmer, who claimed recently that “Donald Trump is going to make punk rock great again,” and that “if the political climate keeps getting uglier, the art will have to answer.” Her comments were echoed by Conor Oberst, lead singer of Bright Eyes, who claimed that “art does thrive in adversarial times.”

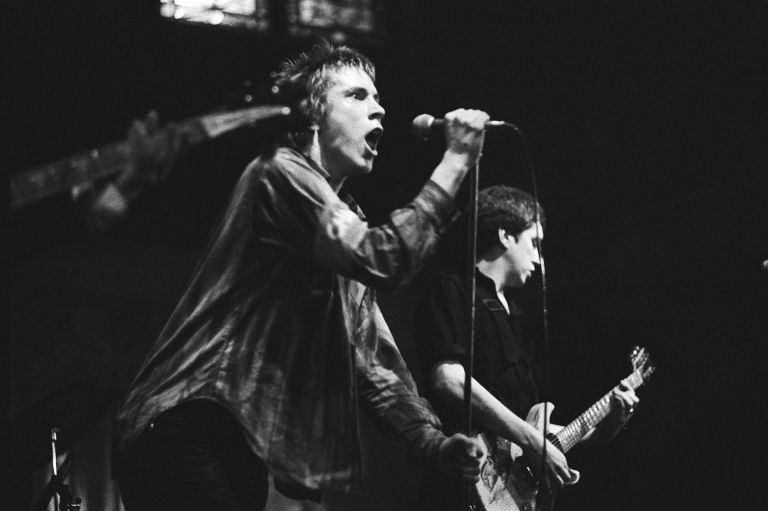

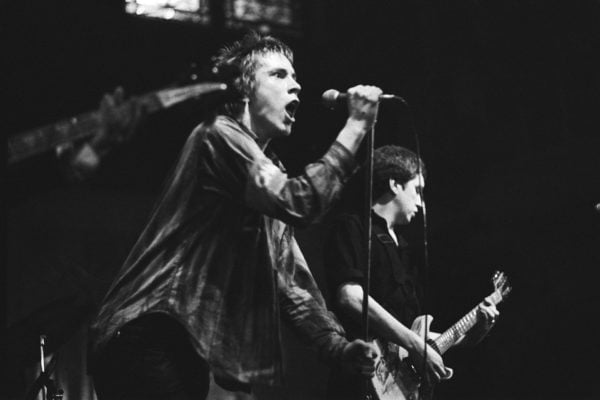

On a surface level, these claims seem to make obvious sense. There’s a long and storied history of music as protest, from “We Shall Overcome” and the civil rights movement to the anti-Bush and anti-Iraq War battle-cries of the 2000s (including, notably, Oberst’s own “When The President Talks To God”). Yet upon closer observation, there’s more nuance to musical history than a model of simple reaction to political oppression and strife. Musicians have made great art under totalitarian regimes and permissive liberal democracies — and all societies between and beyond them — with intensely political and equally apolitical motivations. Even looking at the birth of punk rock, perhaps the most political of major musical genres, we see a great diversity of political viewpoints — from the gleeful lawless iconoclasm of the Sex Pistols and the studied leftist poise of The Clash to the apolitical scruffiness of the Ramones. As punk expanded in the 80s, so did the political viewpoints of its practitioners. Two of the most notable punk groups of the 80s were the anarcho-socialist Dead Kennedys, whose frontman Jello Biafra once ran for the mayorship of San Francisco on a platform of making businessmen wear clown suits, and the neo-nazi Skrewdriver, a group that fundraised for the British National Party and the National Front. Punk rock, just like any musical genre, is a tool, and can be used by musicians of any stripe.

Of course, this is not to ignore that punk rock and music in general have typically had a leftward tilt — just compare the lineups for the inaugurations of Presidents Trump and Obama and the upswell of protest music that followed Trump’s election. Yet, instead of expressing some excitement at the prospect of musicians having more material for protest songs, it’s perhaps more prudent to recognize that having a culture that values free speech and creativity is the most valuable thing to ensure a healthy environment for musicians. While it’s easy to cheer on protest punk when you’re living in Australia for the next five years as Amanda Palmer is, it’s certainly harder to actually write songs when you also have to worry about losing your health care, being put onto a watch list or being deported. Music is undeniably valuable in times of peace and times of strife, but it is fundamentally secondary to concerns of life and death — dead men sing no songs, no matter how many they inspire. There’s something romantic and heroic in the idea of the starving artistic visionary, bravely raging against the machine, but even speaking as a music critic, I’d rather have bland music made in peace than masterpieces born out of collective suffering. All the great punk in the world doesn’t make up for an oppressive government.

Contact Jacob Kuppermann at jkupperm ‘at’ stanford.edu.