Anyone whose labors take him into the far reaches of the country, as ours lately have done, is bound to mark how the years have made the land grow fruitful.

So begin my 700 favorite words in the canon of American journalism.

Every year on Thanksgiving Day, the Wall Street Journal reprints Vermont Royster’s editorial “And the Fair Land.” Some might wonder why. “And the Fair Land” embodies pretty much everything the movement towards modernity has set out to eliminate. It is written in purple prose that borders on the verbose. It pays lip service to America’s problems, but it assigns no blame, and for many today, the desire to unify is derided as the public face of cowardice. It is written from a perspective of great privilege. It glorifies the American experiment with unapologetic admiration.

Ha, ha, some wags might say. That’s exactly why the Journal runs it.

Ha, ha, some Stanford wags might say. That’s exactly why Winston Shi likes it.

I suppose they’d be right on both points.

***

America, though many know it not, is one of the great underdeveloped countries of the world; what it reaches for exceeds by far what it has grasped.

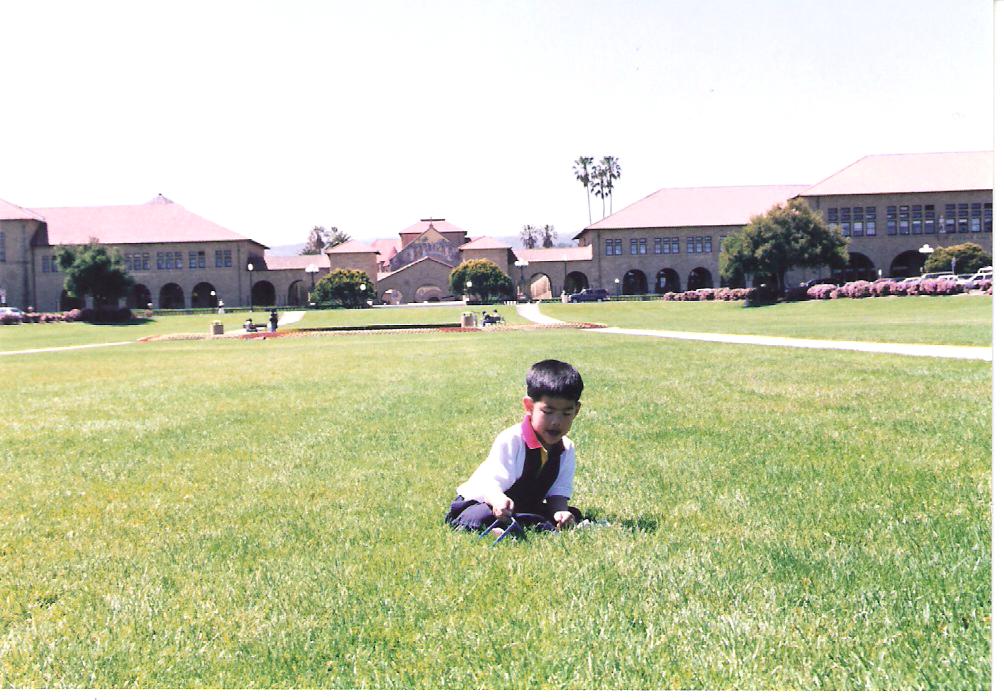

One hundred and twenty-five years ago, Stanford University was founded. Four years after I began my time at Stanford, I remain perplexed by the fact that so much of my identity is tied to a university built by the most infamous person in Chinese-American history. But like the country that inspired its founding and made it great, Stanford is a school full of promise and wonder and brilliance and contradictions. It has always been.

Today, we are most popularly viewed as the university of Silicon Valley, but even many of the people in startup culture here might concede that it’s hard to define what that even means: Today, innovation and looking forward are, for good reason, derided as buzzwords. But they are also an ethos, and as an ethos they turn the future into the present, both through science and through shifting the perspective of the human mind. With impertinence and imperiousness, Stanford offers itself not just as the best example of America’s present but a vision for its future.

As the Editorial Board wrote its final piece for the year, I suggested that Stanford was the university that had captured the American zeitgeist. Everybody — myself included — immediately started giggling at the sheer pretentiousness of that statement. But there is something to Stanford that I still believe embodies something special about the American experience.

***

So the visitor returns thankful for much of what he has seen, and, in spite of everything, an optimist about what his country might be. Yet the visitor, if he is to make an honest report, must also note the air of unease that hangs everywhere… How can they turn from melancholy when at home they see young arrayed against old, black against white, neighbor against neighbor, so that they stand in peril of social discord.

Stanford is a curious place: a university built in the service of meritocracy, but a place of privilege nonetheless.

At Stanford, I’ve found that we’re relatively willing to acknowledge that the deck is stacked in our favor. Neither Leland nor Jane Stanford could have imagined the great firms of Silicon Valley or the glittering towers of San Francisco when they chose to build their university here. Nevertheless, today their legacy sits at the nexus of the world’s economic future, and that nexus continually pays tribute to the university that helped create it. More money flows into this school than any other university in the world. And ingrained into the DNA of this school is the old, historical understanding that there is greatness in the frontier — in both the continent and cyberspace — if you take the time to work at it. It was not for nothing that Leland Stanford left Albany for the West so many years ago.

It is only in the last four years that people have seriously brought up Stanford as a contender for the title of “best school in the world.” Both the principle and the criteria designed to support that principle make no sense to me at all. Stanford’s ivory towers may gleam, but if you do not fit in here, there is little the ivory towers can do to help. And it makes no sense to say that Stanford was the second-best school in the world one year because it had a low undergrad admissions rate and the best the year after because that admissions rate sunk just a little lower.

Nevertheless, institutionally, Stanford is thriving in truly wondrous fashion. This is the “it” school. This is the place. These are the people.

At the same time, socially, Stanford appears to be tearing apart at the seams. In the last four years here, I have seen the campus climate deteriorate, students turn against each other, communities degenerate into mutually exclusive bubbles of private Stanford experiences.

All the while, we increasingly realize that there are two Stanfords: the Stanford that sets the pace for the world and the Stanford that feels shackled to its country’s past. What we fear the most is that the promise of the former cannot exist without the depredations of the latter.

At Stanford, our greatest fear is that behind the façade of sunshine and blue skies lie darkness and moral rot. We can deal with things that we can see every day. We are scared of things we do not think can happen here, or things that we believe we have left behind. We hear it all the time. “It’s 2012.” “It’s 2013.” “It’s 2014.” “It’s 2015.” “It’s 2016.” Sexual assault. Racial tension. Stanford believes it is the future, and we’re terrified of things that we think humanity has confined to the past.

Stanford is not an angry campus. But it is getting angrier.

To what extent is Stanford, as an institution run by mortal men, to blame for its failings? I sense that political opportunism, more than anything else, is what has sundered Stanford so convincingly. The more successful John Hennessy and John Etchemendy became in building Stanford, the more people here sought to use their achievement to gain publicity — rightly or wrongly — for personal or ideological ends. This is not a perfect university, but it is a school that is trying to do things right. Stanford is not at the heart of the problem. And while politicking is a natural part of greatness, the deterioration of the idea of the “Stanford community” worries me.

Nevertheless, as even Vermont Royster understood, there is no path forward for Stanford — or for America — without an honest, convincing and ultimately successful attempt to right the wrongs of the past and present.

Stanford, seeking to position itself at the pinnacle of American meritocracy, unapologetically exists to stand against the idea of equality of outcome.

But Stanford, and institutions like it, have no legitimacy without assuring equality of opportunity.

***

But we can all remind ourselves that the richness of this country was not born in the resources of the earth, though they be plentiful, but in the men that took its measure… And we might remind ourselves also, that if those men setting out from Delftshaven had been daunted by the troubles they saw around them, then we could not this autumn be thankful for a fair land.

We believe that we can create a new future, and in doing so we can transcend the shackles of our past. Leland Stanford may have stopped my ancestors from stepping on American shores for generations. But today, the name “Stanford” does not stand for the Governor. It stands for this university, and it stands for you and me. Perhaps someday it will also stand for what we we hope we can eventually become.

Until then, we must take heart in the fact that Stanford, despite the curious unreality of its worldly perfection, is a microcosm of reality: It mirrors our loves and pains, successes and failures, tears and cheers, until its absence becomes unimaginable. The love all of us have for Stanford comes from the fact that it genuinely did make so many of our dreams come true. The despair all of us at times feel here comes from the fact that we trusted it to be the theater of our dreams, and at times Stanford fell short.

I bought into the vision on day one, and I believe in it still. But I have also had a set of experiences that have convinced me that that vision can truly be realized. I was very lucky to get almost everything that I wanted from the school that, for as long as I can remember, was the university of my dreams. The more I reflect on my experience, the more I realize how fortunate I have been. Stanford was not perfect, but it was the right place for me. And frankly, I’m scared to say goodbye.

But even the most optimistic of us all would have to concede that our future lies beyond Campus Drive. College tells us to push on further, to expand our vision and to become worthy of the opportunities that fortune has handed to us — to move on to the active work of life.

It’s time for me to march on towards my own new horizon. But we are only able to boldly reach for the future because we first came of age in a fair land.

Contact Winston Shi at wshi94 ‘at’ stanford.edu.