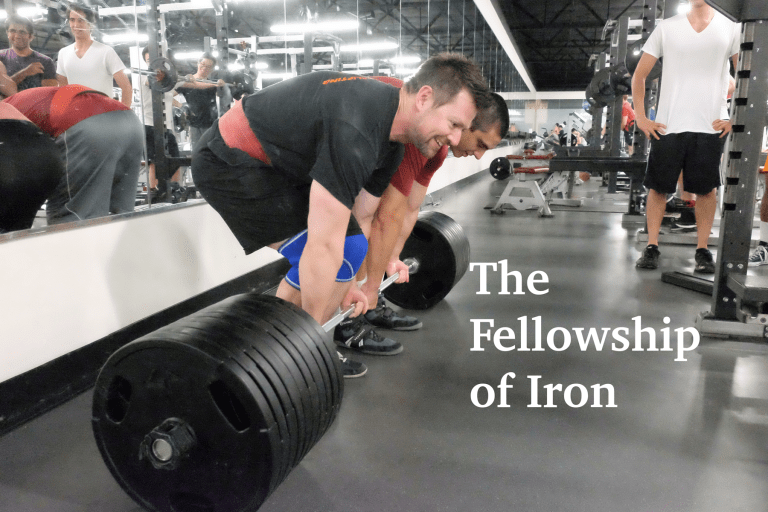

It’s a few minutes past 7:20 p.m. at the Arrillaga Center for Sports and Recreation. “Ex’s and Oh’s” plays faintly over the loudspeaker as two Stanford powerlifters line up to attempt a feat that they never have before: a 1,015-pound tandem deadlift.

It isn’t the most serious of challenges, and both later admit they probably wouldn’t have tried it had they not been in front of a camera. Still, the excitement around the gym is palpable as sophomore Alex Sowell and postdoctoral fellow David Jurgens prepare to jointly raise a barbell that weighs more than a grand piano. A group of different members of their lifting squad, a gym employee and a number of others who have briefly put their post-dinner workouts on hold begins to gather as the duo searches for ways to jury rig more plates onto the already overburdened bar.

Finally, it’s time. After a brief countdown and some scattered applause, the two begin to elevate the weight, slowly at first, but with increasing confidence as it proceeds up towards their waist. Jurgens lets out a bit of a celebratory chuckle at the top before a spotter yells “down” and the barbell thumps back to the ground.

Today may not be just any day for the Stanford’s “unofficial” powerlifting squad, but it seems as if everyone wishes it could be. A Ph.D. student who is with the group, Alexander Papageorge, quips that meaningless routines like the tandem deadlift are what the sport is really about. The bystanders laugh in agreement before moving towards their next exercises so they can finish their routines before they get “cold.”

Filling the void

For a school with the athletic pedigree of Stanford, weightlifting has been notably absent as a mode of accomplishment. A few sports programs, most notably David Shaw’s football regime, have often spoken of the comparative advantage that they build through their workout regimens, but generally these units have treated it as a means to an end rather than an end itself. Neither the Cardinal’s 36-sport varsity athletics systems nor its supplemental 32-sport club program directly offer powerlifting to the Stanford community, and the only listed class that references building strength seems to actively dissuade expert participation with its title, “Weight Training: Beginning.”

Little by little, this motley crew of Ph.D. students, researchers and a couple daring undergraduates is, half by accident and half out of necessity, causing this to change. The group now meets each Monday, Thursday and Friday in the “old gym” to work on their own routines and give each other advice about how to take their routines to the next level.

Nobody seems to know exactly when the squad got together for the first time, probably because it resulted more from a confluence of subgroups than from a single formative event. The earliest origins trace back to when Alex Antaris, Ben Snyder and a few other buddies who studied chemistry together decided to unify their lifting schedules.

“We all just saw each other in classes and lab and in the gym and started hanging out,” says Antaris. “Then, basically everybody that lifts a certain amount just kind of gravitated together. Everybody was just like ‘Sick, nice numbers,’ and then we kind of formed a group that way.”

Gradually, the group expanded to include Jurgens, Sowell, Papageorge and a handful of other from different schools and departments but with a common goal of getting strong. The arrival of Jurgens in particular brought a huge amount of expertise and experience to the growing program. The Decatur, Illinois native cofounded and coached UCLA’s power lifting team for seven years while earning his Ph.D., and his number of completed meets numbers “somewhere in the 20’s or low 30’s.”

“I was coaching [at UCLA] for a long time and was doing like three, four or five meets a year,” he said.

A memorable moment for Jurgens came at the 2011 USA Powerlifting Raw Nationals, when he finished second to Anthony Parrella in the 90-kilogram weight class. “I had to pull a huge personal record [to win] and I almost got it,” Jurgens said. “I was like an inch away. But the thing is in powerlifting you’re still a community. You still recognize the other dude is in the gym grinding just has hard as you. And so [Anthony’s] on the side cheering for me, and his coach is cheering for me, and everyone’s like ‘Come on, you’ve got to do it.’”

Though Jurgens is the clear leader in terms of mastery, everybody in the group plays a role in contributing advice and encouragement to its other members. “There’s a lot of bro-science. Like ‘Yo bro, this works,'” says Antaris. “I think with [lifting] there’s not really one right answer. There’s a lot of ways of thinking, there’s a lot of different types of programming.”

Part of this is because there are so many routines and programs that everyone can be interested in pursuing. Jurgens describes the weightlifting world as a square, with one axis separating slow versus fast events and the other separating the more technical events from the “strongman,” or functional challenges. Powerlifting, which consists of the squat, the deadlift and the bench press, sits in the top corner at slow and technical. Olympic lifting, or rapidly moving plate-loaded barbells, sits below it as faster activity that emphasizes the same precision. Pure strongman, meanwhile, is in the top right, while highland games, an event that traces is origins to the culture of traditional Scottish Highlanders, occupies the final corner with its emphasis on functional strength at speed with events like the tree-flipping caber toss.

Most members of the lifting squad have thus far focused on powerlifting, which has the most formalized competitive landscape in the United States. There’s plenty of exploration into other areas, however, and Jurgens has tried a bit of everything in the past. A personal favorite of his: pushing cars around the track while at UCLA.

“You need a few guys, but you’re pushing yourself to the limit,” Jurgens says. “It’s like what’s your 100-meter time when you’re pushing a Toyota Corolla. You can get into it.”

A mental game

All these activities require intense physical strength, but developing the right mentality to accomplish them is equally if not more important. Much of the reason for the squad’s existence comes through pushing each other through these mental hurdles, which can range from questions of technique to the sheer difficulty of adapting your life around lifting.

“It’s really hard to be motivated by yourself,” Sowell admits. “That’s something I found when I got here and was just trying to lift for general purposes…Having people pushing you or jawing at you or kind of making fun of you while you’re lifting…gives you a little more motivation to go and lift some heavier weight.”

While it is in some ways their greatest obstacle, this mental challenge is also one of the biggest reasons why many of the team members enjoy lifting. Papageorge, who researches cold atom physics in his graduate program, likes to examine his motions in terms of classical mechanics in order to identify the parts of his body that are impeding him and improve his ability to execute more technical routines.

“All your muscles are generating torque with your joints as fulcrums…It’s not always just as simple as saying you’re not strong enough. You have to determine which part of your kinetic chain bears the weakness.”

Many of the others approach lifting from a problem-solving perspective, rigorously defining and testing different parameters to get them to their next level. Sowell views lifting as a bit of an engineering challenge which only optimization and sustained effort can solve.

“I love the mental toughness that [lifting] requires. That and the commitment you have to put to it. It’s something that you can’t just do once a month or once a week even – you have to be in consistently three to four days a week, have a plan, watch what you eat. It’s very methodical, very scientific. As an [electrical engineering] major, I love numbers and math and statistics and all this stuff, so it’s a good way to fulfill my hunger for both mental and physical improvement.”

Snyder, a chemistry Ph.D., has a similar view: “I think there definitely is something to being analytically minded, both in terms of writing a program that you stick to…a lot of things like ‘Oh what happens if I place my hands here versus here on a bench press.’ And in some sense, I guess, maybe thinking about it scientifically is a little bit of a stretch, but we’re all kind of trying new things out and seeing what happens.”

Naturally, these processes can’t happen overnight, and finding the time in a busy Stanford schedule is particularly difficult for many of the unofficial athletes. To some extent, the squad has even engineered a solution to this aspect of the sport. Senior Chris Billovits, the team’s only undergraduate besides Sowell, claims to have seen reasonable success by optimizing his routine in the busier times of the quarter.

“It becomes hard to come more than three days a week… toward the end of the quarter and sometimes I end up coming in two. I just adjust my work schedule to do the same amount of work I’d do in three days in two. It ends up being ok, and then I come back with more fervor at the beginning of the next quarter.”

Bringing it all together

The carrot at the end of the stick for most of these lifters is the prospect of proving themselves in a competition. Everyone has a slightly different view of the importance of these formal events, though almost every member of the squad has competed in an individual meet or plans to in the future.

Sowell is one of the more recent additions to the competitive lineup, participating in a meet at San Jose State on February 29. Despite it being his first time in competition, the Texas native captured the California state records for 19-year-olds in the squat and all-around categories and qualified for nationals next October.

“I’ll have to compete within the 20- to 23-year-old age class [at nationals], so the competition’s going to be a bit stronger,” Sowell said. “I don’t expect to go in winning, but when I get to 22, 23 maybe I’ll have a shot of winning and competing at the world stage.”

Antaris and Snyder have each done a couple competitions in the past, though both have been unable to in recent months because of injury. Both are getting back to strength now, however, and hope to compete in a meet this summer.

“I don’t know if the competition aspect of it drives me so much to be honest,” says Snyder. “I mean it’s cool since numbers you put up at the gym just don’t really count for much. When you’re doing it under the strict requirements that are put forth in competition, those are the numbers you take seriously. For me, at least, I think I enjoy the process much more than the competition itself.”

Billovits is also building for a competition, which he’ll begin considering once he hits his current weight goals. There’s also the prospect of competing more directly for the school, as USAPL operates a collegiate nationals in addition to its various individual events.

The group doesn’t have any immediate plans to enter this highly competitive event, though with younger members like Sowell showing promise it certainly seems a possibility in the future.

Not everyone is motivated by the prospect of entering these formal events, however. Papageorge doesn’t consider himself a competitive person, and lifts with the squad purely for the relaxation and personal satisfaction it can provide.

“I think it’s just exciting trying to hit the next goal…There’s something extremely pleasing about watching yourself progress, which I think applies to any sport, of course, or any training system, but it’s very transparent here. There’s just literally more weight on the bar. Lifting it is fun.”

For Jurgens, meanwhile, his days of competition have still just begun. Though he’s already been lifting for most of the lifetimes of some of the other group members, his numbers are running strong and he sees himself continuing to train for many years in the future.

“The oldest competitive guy in my weight class is like 57…I ran into this one dude at worlds, he was like 62 and he [told me] ‘I have to deadlift 600 pounds this year before I get old.’ I’m like dude, what on earth. You are pulling more than most humans will ever pull.

“It’s not a sprint, it’s like a sport for life.”

Contact Andrew Mather at amather ‘at’ stanford.edu.