Twice a year, Building 110 becomes mission control for the nation’s second-largest Splash event. Splash programs are held on campuses across the country and even on one campus in the U.K., and they are all independently run and funded. The idea is simple but ingenious: College students teach what they love to students who want to learn.

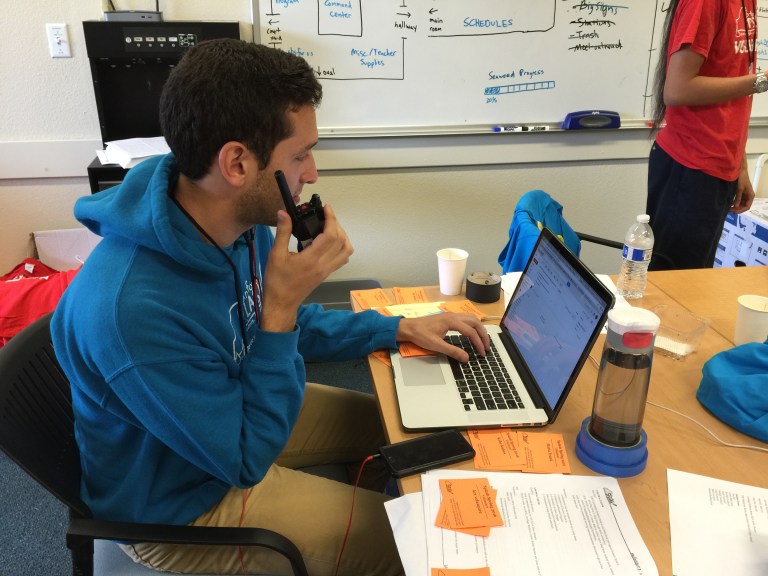

Organizing a two-day long program for 1,300 middle and high school students is no easy feat. Building 110 is a whirlwind: Pamphlets are scattered across multiple folding tables pushed together; packets of trail mix and dried mangoes are littered here and there. The administrative team, indicated by their turquoise blue shirts, are all vigorously typing away at computers or yelling orders into walkie-talkies.

But there is, above all, an order to the chaos.

I find Nick Rodriguez ’18 at the end of the table. He’s speaking rapidly into his phone in a clipped, professional tone. He wraps up the message before greeting me. He looks incredibly alert despite the fact that he’s functioning on less than four hours of sleep.

“Did someone not show up?” I ask, regarding the message he left.

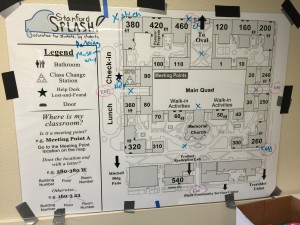

He indicates a color-coded version of the Stanford Splash website. “At the start of every hour, we check and see what teachers haven’t checked in for their classes. And if they haven’t checked in yet, we give them a call.”

Nick is the co-director of Stanford Splash, so I ask him if he’s in charge of running the show. “[There are] two presidents and financial officers, as well as teams of admins. Each team has a team share, like teacher logistics, teacher development and student experience.” The teams are in charge of everything from teacher training to recording student satisfaction surveys and teacher reviews.

Friday, the day before Splash starts, is surprisingly the longest day of the weekend for the Splash team. “Friday’s an all-day thing for everybody. Some people have to go to Costco to buy food and drinks from about 9 to 12. We also have a truck that goes to our storage unit at 1, and by the time we unload everything on campus, it’s about 6.” A few of the leaders of Splash, Nick included, stayed to set up finishing touches until 1 a.m. the night before, two hours after the rest of the Splash team left around 11 p.m.

Throughout our conversation, volunteers poke their heads in the doorway with different inquiries: “Where’s teacher check-in?” “We need to pick up the parents from the tour in five minutes.”

Most students at Stanford Splash pay the $40 registration fee, but Nick tells me about the four outreach schools that Stanford Splash helps waive fees for. “They’re schools from minority or lower-income communities that may not have known about Splash or may not have the means to come to Splash otherwise,” he says. Splash organizes tuition waivers and transportation, if necessary, for these students.

After students arrive at 8:30 a.m. the Splash classes run from 10 a.m. to 5 p.m. on both Saturday and Sunday, with lunch breaks. I learn about the efforts Splash has made to reduce food waste as well. “SPOON (Stanford Project on Hunger) is supposed to come and pick up the leftover boxes of pizza today. We also have compost bins all around the lunch area,” says Nick, which reminds him to walkie-talkie to check in on the lunch clean-up. Immediately after, he helps a lost student and reminds another volunteer that Splash t-shirts are for sale for $10.

To me, it seems like the swarm of kids with their parents is enormous, but Nick remarks that Splash is actually smaller this year. With the new limitations on teachers that are not Stanford-affiliated, they haven’t been able to accommodate as many students as years before.

Still, I’m impressed by the scope of the program: 60 to 70 Stanford volunteers, 300 teachers, 25 administrative members and two advisors, Ankita and Rosy, from SAL and Haas. There are even a few “exchange” students from the leadership teams of other Splash programs at UNC, Pomona, Yale, Berkeley and other schools, here to learn about how Stanford Splash is run.

And all this again tomorrow? Nick nods, adding that they also have to clean up and move everything back to the storage unit at the end of Splash.

The phone goes off. A volunteer surreptitiously adds a tally mark to the whiteboard in a column marked with a musical note. There are already three tallies.

I leave Nick to his job and walk out to Main Quad. The Quad looks radically different from its weekday state, with lanyard-sporting preteens trying to find their next class, tired-looking parents waiting for their kids and incongruously, a wedding party. This transformation is a lot like that of the team in Building 110, who on Monday go back to their regular lives as students, but for now are commanders of the largest Splash event on the West Coast.

Contact Samantha Wong at slwong ‘at’ stanford.edu