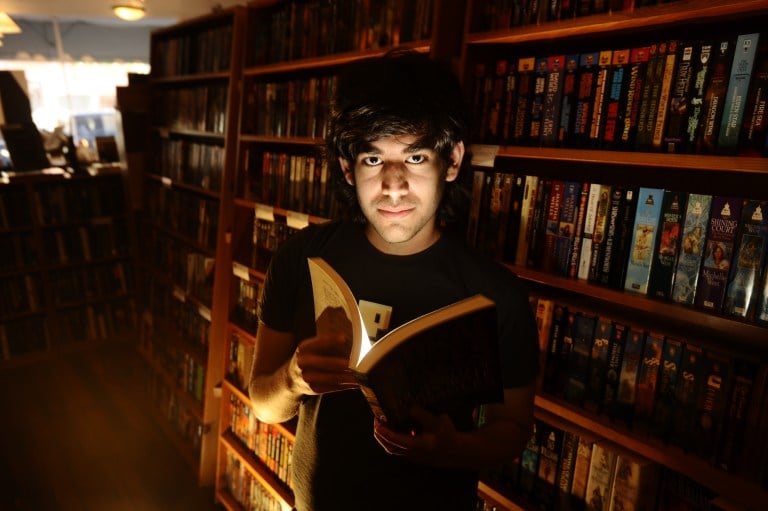

In January 2013, Aaron Swartz — transparency activist, innovator, prodigy — hanged himself at age 26. In the days that followed the tragedy, a poem by Tim Berners-Lee, purported inventor of the World Wide Web, surfaced atop a Reddit comment thread in January 2013: “We have lost a mentor, a wise elder. Hackers for right, we are one down, we have lost one of our own.” Perhaps for the first time, according to a new documentary by Brian Knappenberger, the Internet itself was grieving, mourning the loss of one of its brightest minds.

“The Internet’s Own Boy” tells the story of Swartz’s life and death through interviews with friends, family and colleagues, as well as archival footage of Swartz himself. Knappenberger’s film is not only a homage to Swartz’s spirit and achievement, but also a call to action, which urges viewers to take up the crusade for freedom of speech and information online.

We first meet Swartz through home videos of his childhood, as he teaches himself to read and persuades his brother to dress up as a Mac computer for Halloween. His brothers, Noah and Ben Swartz, remember him as a boy who “learned how to learn at a very young age,” who believed that “programming is magic — you can accomplish things that normal humans can’t.”

As a young teenager, Swartz was instrumental in developing RSS, a system for summarizing frequently updated sites, like blogs or news outlets. He also devised the technical infrastructure for Creative Commons, which provides a “some rights reserved” copyright framework for reusing online creative material. At 19, he enrolled at Stanford — but, as his friend Cory Doctorow describes, he found himself in a “babysitting program for overachieving high schoolers … it just made him bananas.” He left Stanford after one year to found his own company, Infogami, which soon merged with Reddit, the free and anonymous information-sharing site for which Swartz is most famous.

Knappenberger’s film does a good job of illuminating that Swartz’s contribution is heroic not for the gamut of his technological innovation, but for his dogged commitment to fixing the world he inherited. As Swartz himself described, “Growing up, I slowly had this process of realizing that all the things around me that people had told me were just the natural way things were … were wrong and they should change. Once I realized that, there was really no going back.”

Eventually, Swartz’s quest to promote transparency and freedom of expression took him beyond start-up culture: turning his attention to political activism, he founded Demand Progress, a political advocacy group to promote civil liberties. In 2012, Swartz was a major actor in a major victory for transparency activists: he helped led the campaign against passage of The Stop Online Piracy Act (SOPA), a bill thought to impose undue copyright burden on web publishers.

At the time of his death, though, Swartz was facing federal felony charges for downloading JSTOR’s license-protected academic research journals though MIT’s network. In all likelihood, Swartz was motivated by his long-standing desire to liberate academic research from clutches of for-profit publishers, but, according to the film, the Obama Administration’s Department of Justice was intent on “making an example” of Swartz. His thirteen-count indictment meant he faced up to 35 years in prison and a $1 million fine.

“The Internet’s Own Boy” is clear about its contention that overzealous prosecution and unfettered government are to blame for Swartz’s death. Knappenberger portrays the suicide as the product of a particular political injustice, rather than a conspiracy of psychological and physical factors, including Swartz’s history of ulcerative colitis and clinical depression. Knappenberger’s approach is consistent with the Swartz family’s efforts to channel grief and sadness around his death toward productive, political purposes.

Of course, the truth of any person’s inner-world is far more complicated than a legal battle. In a riveting piece in “The New Yorker,”Larissa Macfarquhar argues that the Swartz family publicly blamed the government for Aaron’s death in order to rally support for causes close to Aaron’s heart–but “the people closest to him don’t really believe” his suicide was purely a response to his indictment.MacFarquhar’s profile is a step towards remembering Swartz not only as a symbol of the potential links between progressive politics and digital innovation, but also as a young man, vulnerable to the throes of uncertainty, disappointment, and fear — who bumped up against an unforgiving, unjust reality.

“The Internet’s Own Boy,” on the other hand, misses an opportunity to discuss the prevalence of suicide in this country and elevate our conversation around mental health. Instead, the film almost propogates the dangerous illusion that prodigy or success provides immunity from more banal — or perhaps universal — challenges of the human condition.

In the film, Harvard Professor Lawrence Lessig tears up while discussing Swartz’s death: “I feel, and everybody else does too, that there was so much more to do. I didn’t know he was there. I didn’t know this is what he was suffering.” Doing justice to Swartz’s short but shining life may mean getting better, collectively, at helping each other feel well.

Knappenberger was right to identify that Swartz’s story is one that deserves telling, but he never exposes its rich and productive ambiguities. Swartz’s work — his innovations, writings and political footprint — reminds us that the boundaries between inner, outer, and cyber-worlds are blurry and, at times, bloody. So long as “magic” of new technology rests in very human hands, we must ask ourselves how to make these worlds more just, more happy.