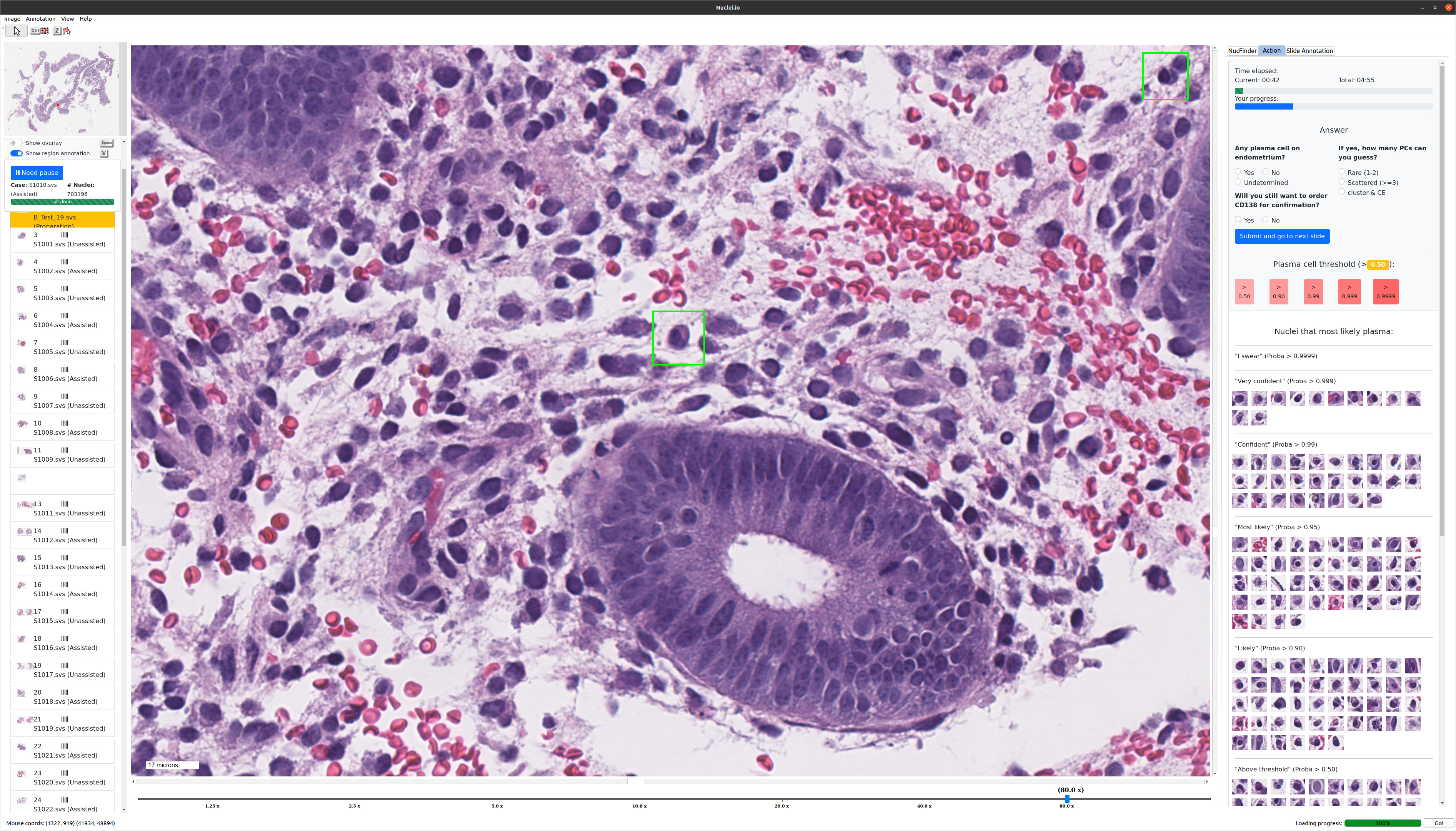

Stanford Medicine physicians and computer scientists have collaborated to develop nuclei.io, a customizable AI tool that can identify diseased cells under a microscope.

The tool, which appeared in a Nature Biomedical Engineering paper published on June 19, seeks to enhance efficiency for healthcare professionals tasked with diagnosing diseases.

Pathologists, or medical professionals who examine tissues and body fluids to diagnose diseases, often grapple with identifying rare abnormal cells among a sea of healthy ones. AI tools, especially in the realm of digital pathology, can offer speed and precision in this process.

Nuclei.io sets itself apart from other AI-based healthcare tools by using machine learning to create a system that adapts to the workflows and preferences of the pathologists who use it.

“This is one of the first tools that enables personalized assistance, that adapts AI models through an active learning approach to personalize it to the needs of individual doctors,” said associate professor of biomedical data science James Zou, who was a co-senior author of the paper.

Rather than seeking to replace the expertise of pathologists, nuclei.io aims to enhance it, improving the accuracy and efficiency of diagnoses in the process.

“Humans are human. We can sometimes miss something, or our mind wanders for a minute,” said Dita Gratzinger, a pathology professor also involved in the project. “The beautiful thing about working with this program is that it’ll find the little cluster of cells that… the pathologist might otherwise have missed.”

According to Gratzinger, the collaborative nature of this innovation, where pathologists work alongside AI to confirm identified areas of concern, reduces the risk of human error and enhances the quality of patient care.

While the potential of AI in pathology is immense, there are challenges in providing tools like nuclei.io with enough data to learn how to identify abnormal cells. Eric Yang, a pathologist who helped develop nuclei.io, highlights the difficulty in gathering sufficient training data. However, with the use of active learning, Yang said that the training process becomes more efficient. By allowing the model to learn from the most informative data points, active learning reduces both the time required to train the model and the overall amount of data needed.

Yang said this capability is crucial in scenarios like identifying plasma cells in chronic endometritis, an inflammatory or infectious condition within the endometrial lining that can affect fertility.

In cases of chronic endometritis, pathologists are tasked with identifying plasma cells in endometrial biopsy samples. Manually identifying these cells is challenging, as they are small, round, blue cells mixed among thousands of similar-looking cells. The nuclei of these plasma cells have distinct clumpy chromatin, which is DNA coiled up on itself, and a nuclear “hop,” which is a noticeable change in the position or shape of the nucleus that makes them slightly different from surrounding cells.

However, spotting these subtle differences in a sea of similar cells is a tedious and time-consuming process, like “finding a needle in a haystack,” according to Yang. This is where nuclei.io proves invaluable, as it can be trained to recognize specific characteristics within cell nuclei and learn from a physician’s feedback.

While nuclei.io has already been used in clinical studies at Stanford Medicine, its open-source nature allows it to be adopted by other institutions as well, broadening its potential impact on healthcare.

Jeff Liu ’26, who studies AI, said that an ideal outcome would be for tools like nuclei.io to become so optimized that it eliminates the need for human involvement in the disease diagnosis process.

“We might need some human to manually double-check if the results are correct,” Liu said. “But we ideally want no humans to be involved in this process, because that will greatly reduce the cost of processing different samples.”

As the field of AI-assisted healthcare progresses, Yang says that maintaining a balance between automation and human oversight will become increasingly important. Technology should enhance human capabilities rather than replacing them.

Yang notes that while the nuclei.io highlights potential abnormal cells, it doesn’t make disease diagnoses itself, allowing pathologists to examine them and make the final call.

“It’s helping us get faster, but it’s not necessarily making a diagnosis for us,” he said. “I think this is a great way to use AI at this point.”