For most students, the closest opportunity to directly engage with medieval European psalms, classical Chinese poetry, early Islamic manuscripts or other historical artifacts is observing glass-enclosed displays at a museum or archive. However, through Green Library Special Collections, visitors are encouraged to use their bare hands to examine the department’s fascinating and diverse collection of hundreds of papyri, manuscript leaves, fragments and bound codices, covering thousands of years’ worth of knowledge from various corners of the globe.

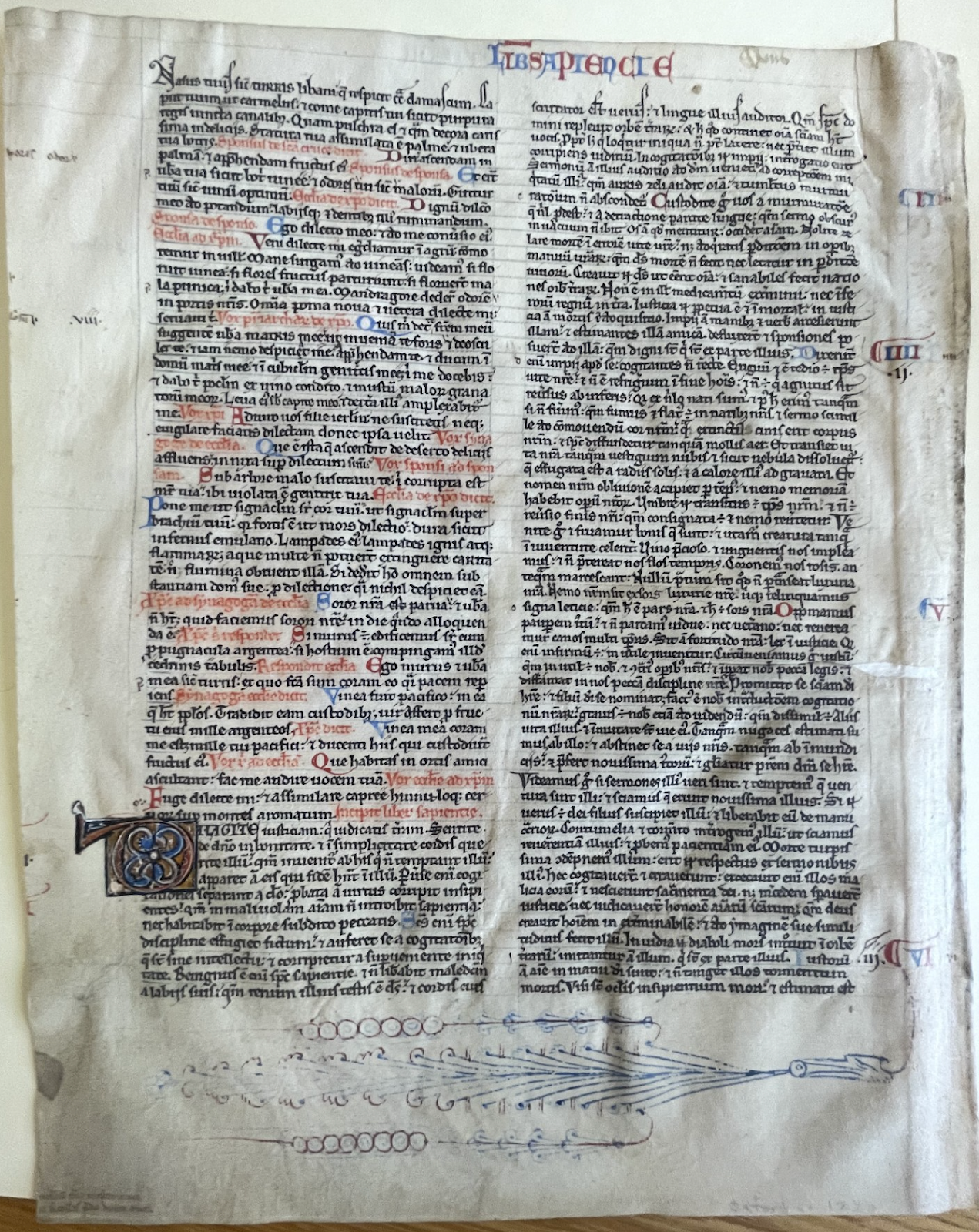

For a research paper in HISTORY 113P: Media and Communication from the Middle Ages to the Printing Press, I chose to analyze an illuminated vellum leaf of the Song of Solomon 2:15-Book of Wisdom 3:2. Created in England between 1225 and 1250, the manuscript was likely a fragment cut out from a Bible.

As part of the wisdom literature of the Bible, the Song of Solomon offers a divine perspective on marriage by affirming the sanctity and potency of human love. The Book of Wisdom captures the nature of wisdom, righteousness and mortality. Both compositions of Hebrew poetry are replete with complex metaphors, symbolism and other literary devices. These texts also oblige the medieval reader to deeply engage with the meaning of the sacred verses, offering a guidepost to help navigate some of the most fundamental questions of the human condition.

Complementing the complexity of the Latin biblical verses, the manuscript features a striking combination of rich imagery, elaborate penmanship and vivid ornamentation that enhances the process of communion between the reader and the sacred text. Beyond its allegorical significance, the manuscript’s material features reflect the unique craftsmanship and personal attributes of the scribe. This offers additional layers of meaning that are embedded within the design, layout and overall architecture of the text itself.

Simply viewing medieval manuscripts as works of art in and of itself offers a rich, captivating sensory experience. In addition to dark brown ink, the Song of Solomon 2:15-Book of Wisdom 3:2 manuscript employs a sumptuous palette of colors, including deep red and lustrous blue. The magnificence of the text is further reinforced by intricate decorations that reflect the scribe’s attention to detail, including examples of penwork flourishing, historiated initials and illumination.

In Special Collections, I became a detective of history. Noting that the manuscript’s gothic handwriting is largely uniform, consistent and elegant, I inferred that the scribe was likely well-educated and possibly well-compensated, and that the bible containing this fragment would have been gifted to a benefactor. Additionally, the abundant space allocated for interpretive analysis and reflection, as well as the presence of considerable marginalia, including signs resembling manicula, attests to the deeply personal nature of the text, and the significance of connecting with God on a transcendental level.

At the bottom of verso (back page), thin, swirling red and blue lines extend from the beak of a bird, which strongly resembles a kingfisher — an animal with Biblical symbolism. As one of the first animals to fly from Noah’s Ark after the flood, the kingfisher was interpreted allegorically by later Christian thinkers as a prefiguration of Christ, according to my professor Jenna Phillips. The illustration of the bird was also likely conducive to memorization and the realization of lectio divina, a form of deeply intimate, contemplative reading practiced by medieval monks.

Demonstrating even greater levels of sophistication than penwork is the use of a historiated initial and illumination. On verso, the prominent and colorful initial ‘D’ (Diligite) is depicted in earthy hues of brown, blue and orange that contrast with a gilded background. With its impressive appearance, gilding signified that the recipient had paid a considerable amount for this manuscript. Alternatively, if the manuscript had been a gift, gilding may have persuaded the recipient to generously compensate the bearer.

Throughout my research, it was difficult to fathom that the text I was openly studying at my library table had been painstakingly created during the aftermath of the Norman conquest — a time when the English language was still undergoing fundamental changes, writing was metamorphosing into an instrument of power and castles were being built across the English landscape as symbols of domination.

To enhance the process of lectio divina and the attainment of the essential truths of the wisdom literature, the medieval reader would find it useful to follow a variety of visual aids to better understand and interpret the text. Much in the way that these visual attributes once helped the medieval reader, analyzing the motivations behind these features, including the script, use of color, reading aids, decoration and marginal glosses, offers a critical lens into the intended purpose of the manuscript while revealing illuminating information about both the scribe and the world in which he lived.

Considered together, the visual elements and the text work seamlessly to convey essential and timeless truths about the human condition, God and man’s place in the universe, that are as relevant today as they were nearly a thousand years ago — as they are placed simply across a table in Special Collections, bound and beautiful.

A previous version of this piece referenced a text as being created during the Norman conquest, when it was in fact create during the aftermath of the event. The Daily regrets this error.