Editor’s Note: This article is a review and includes subjective opinions, thoughts and critiques.

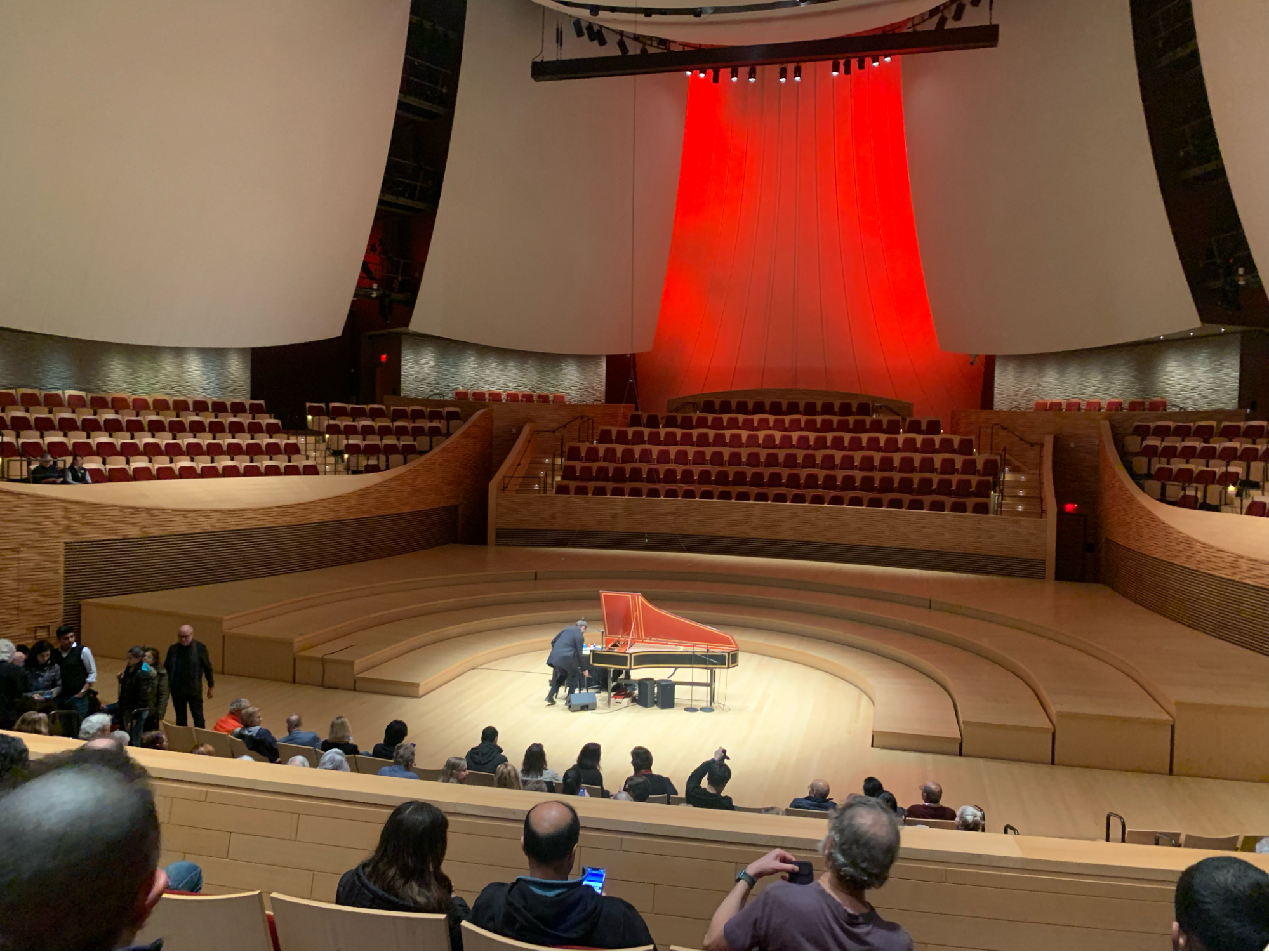

Historical instruments might not be your idea of a fun night out, but Stanford alumnus and professional harpsichordist Mahan Esfahani B.A. ’05 turned that on its head with an incredible program of Tomkins, Bach, Applebaum and Scarlatti during his Wednesday performance.

The harpsichord can’t vary in volume based on finger pressure like the piano can. As such, Esfahani’s expressive performance demonstrated his mastery of the instrument and its complex stops and manuals that permit changes in tone and contrasting dynamics.

The first two pieces were composed by Renaissance/Baroque musician Thomas Tomkins and served as great openings to the concert. Esfahani opened with Tomkins’s “Pavana FvB CXXIII,” playing with remarkable control, beautifully highlighting its melancholy nature.

He then went on to “Barafostus’ Dreame,” a lively theme and variations that presented a sprightly, dance-like theme. With fast moving scales and considerable virtuosity, the piece showcased a taste of the fiery energy that Esfahani would sustain throughout the concert.

Esfahani’s rendition of Bach’s “English Suite No. 2 in A minor” highlighted the characteristics of each movement in a wonderfully cohesive and authentic manner. One of my favorites was the third movement “Courante.” The harpsichordist highlighted the persistent rhythmic meter that was carried along by exceptionally clear counterpoint in a short, lively dance.

Following the lighthearted “Courante,” the “Sarabande” provided an incredible contrast. Esfahani presented the movement’s heavy anguish and penetrative longing with remarkable authenticity and touch. His range in musical expression truly shone through in this movement, with an air of dark solemnity providing for an incredible listening experience.

Stanford composition professor and composer Mark Applebaum wrote the piece that Esfahani performed to conclude the first half of the evening performance. Titled “October 1582,” the song was inspired by the ten days that were cut out from the Julian calendar due to astronomical inaccuracy.

It was the only piece performed from a living composer in the program, as Applebaum jokingly pointed out in his brief speech to the audience. The strong composition utilized electronics, bells and visual cues such as giant post-its that wrote “THE END” at the end of the piece.

It certainly wasn’t my favorite work in the concert, as the atonality felt rather bizarre in its portrayal of each of the ten days. As someone who has never really found the joy in atonal music, I found it rather hard to understand and, consequently, enjoy.

The second half of the concert revealed some of the most exciting and unique renditions of the music of Domenico Scarlatti I have ever heard. The explosiveness and energy that Esfahani brings to his music were truly at their best here.

For instance, in “Sonata K. 28,” Esfahani created incredible vigor through the imitations of Spanish guitar technique Scarlatti embedded in the piece, offering a thrilling adventure through the lively work. I’ve never heard a more convincing and exciting rendition of the piece, and I absolutely loved it.

In the final “Sonata K. 436,” Esfahani coupled his playfulness with virtuosity. He showcased his astounding ability to play with audience expectations by withholding cadential resolutions or playing moderately-paced scales that quickly snowballed into surprising eruptions. Despite these liberties, Esfahani’s interpretation always felt respectful and reverent of Scarlatti’s work, never overstepping the bounds the composer set.

I’ve really never heard the harpsichord played with such fiery energy. Esfahani offered a completely new perspective for me on the harpsichord, as he overcame the instrument’s limitations of color and dynamics in such a creative way. Watching his entire body move with each note felt like I was watching a performance that, while entertaining, felt truly authentic in his expression of the music.