Families in Hulme, a graduate residence in Escondido Village, say they have been left panicked and confused after Residential & Dining Enterprises (R&DE) hired a contractor to plant gopher poison in their courtyard without informing residents.

R&DE confirmed in an email to The Daily that it had commissioned a contractor to plant the poison diphacinone, a “first-generation” rodenticide. They wrote that they had not initially alerted graduate students because the residents did not “need to know how to avoid coming into contact” with the poison.

They further wrote that diphacinone did not pose a threat to residents or wildlife. Wildlife experts disputed this account, citing the risks the poison could pose to residents, their children and wildlife.

The incident, which students have begun referring to as “GopherGate,” has especially alarmed graduate students with young children, whom they worried could ingest the poison.

Hulme resident Ryan Meservey ’22 wrote that he was most concerned about the impact the poison could have on children like his young son, Tad, who enjoys playing in the courtyard where the poison was placed.

“I had a long talk with my 3-year-old son about not eating anything in the courtyard,” he wrote in a statement to The Daily. “I feel sorry for parents with even younger kids — really young kids will put anything in their mouths.”

The incident has inflamed longtime tensions between the graduate student body and R&DE, with which graduate students have clashed over affordability, housing availability and communication issues in the past. Residents said they hoped for changes in the way R&DE approaches pest control to prevent an incident like this from happening in the future.

According to Hulme residents, graduate students raised their concerns to R&DE, both through complaints to community associates (CAs) and the Graduate Life Office, and waited almost two weeks before R&DE sent them an official response.

R&DE spokesperson Jocelyn Breeland confirmed in a statement that the University had hired a pest control contractor to place diphacinone blocks in areas with a large number of gopher holes, which Breeland wrote posed a tripping hazard. She wrote that the University is “confident” that the blocks were properly buried and used in compliance with applicable laws.

“Pest management is part of daily practice throughout the Stanford campus, with routine monitoring and timely response to the presence of pests,” she wrote.

Crane Pest Control, the company contracted by the University, did not respond to a request for comment.

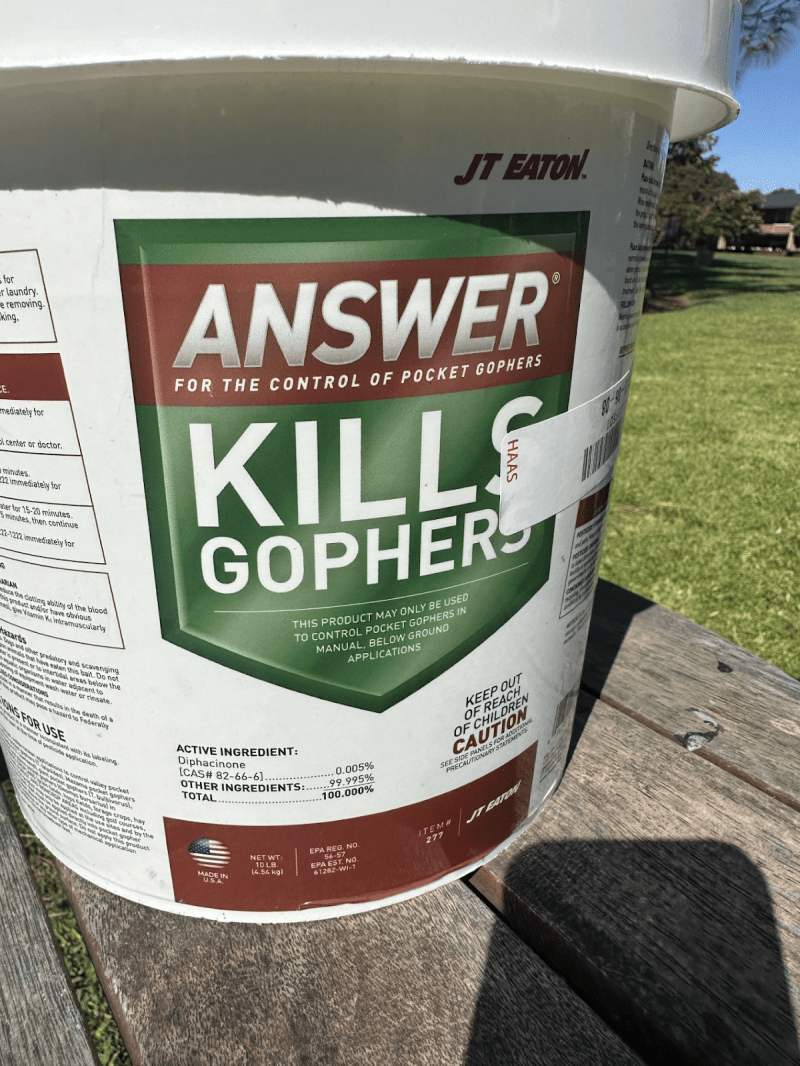

Breeland cited a safety sheet from JT Eaton, the company that manufactures the diphacinone blocks, when writing to The Daily that the poison “does not pose a threat to children or secondary animals.”

Three wildlife experts told The Daily that the poison is toxic when ingested by children and can cause harm to animals that consume the poisoned gophers.

“[T]hese poisons are indiscriminate,” wrote Tiffany Yap, a senior scientist at the nonprofit Center for Biological Diversity. She cited a statistic from America’s Poison Centers, a nonprofit organization representing America’s 55 poison control centers, finding that 2,300 children in the U.S. had been poisoned by long-acting anticoagulant rodenticides like diphacinone in 2021.

In a statement to The Daily, Environmental Protection Agency spokesperson Jeffrey Landis referenced a widely-available EPA document stating that JT Eaton Answer, the diphacinone product used by the contractor, could harm dogs, birds and other animals if they feed upon rodents that have eaten the poison.

Graduate students expressed further concern upon learning that a California law will ban the use of diphacinone starting in January due to research indicating its harms to people and the environment. The law, AB 1322, extends the scope of a prior rodenticide ban passed in 2020.

Breeland wrote that diphacinone is not banned under the new law, as it is a first-generation anticoagulant, which indicates that diphacinone is an older type of rodenticide. The University wrote that the new law only applies to second-generation rodenticides.

However, the new law explicitly extends the impending ban to diphacinone; aside from some exceptions, “the use of diphacinone is prohibited in this state and diphacinone shall be considered a restricted material” starting in January, according to the law.

Four legal experts confirmed to The Daily that diphacinone will be banned under AB 1322 starting in January.

When asked for comment on this information by The Daily, spokesperson Breeland wrote that the University’s diphacinone application is compliant with the current law, but that the contractor would “identify a new product to implement [come Jan. 1] that is compliant with AB 1322.”

Breeland added: “To clarify, a single instance of the product (one 1” x 1” block) was only placed in one gopher hole.” But in emails to residents and previous statements to The Daily, R&DE had referred to the placement of “bait blocks” in “gopher holes.”

The student who said they saw the contractor wrote that that they found it “absurd” that the contractor would use a large bucket to transport a single block. The student, who spoke on the condition of anonymity due to fear of University retaliation, shared a photo of the bucket with The Daily and wrote that they had seen the contractor place blocks into multiple gopher holes.

Independent of safety concerns, the University also drew anger and frustration from some graduate students over what they saw as the University’s inadequate communication about the poisonings.

Multiple students told The Daily that they first found out about the poisonings from another student, not the University. Dead gophers and other rodents then began to appear in the courtyard, a student wrote.

On Oct. 6, a graduate student alleged in a Hulme resident group chat that they had witnessed a contractor placing blocks of poison 2 to 3 inches underground and without the use of child-safe containers.

The Daily was unable to directly verify these allegations, and the student who made the allegations declined to speak to The Daily on the record. Breeland, the R&DE spokesperson, wrote that the blocks were properly buried, and children were unlikely to encounter the product.

A dorm community associate later posted in the chat that Keith Ellis, the assistant director of graduate housing facilities, had “advised everyone to not touch the holes,” according to screenshots provided to The Daily. Ellis did not respond to a request for comment.

Another associate posted a week later that R&DE’s landscape manager had told her the pelleting “was an honest but isolated incident that was an admitted error which has been addressed and will not occur again,” according to screenshots provided to The Daily. The associate further said that the landscape manager was “working with the pest control vendor to ensure that the pellets have or will be appropriately removed.” Breeland did not respond to requests for comment on this claim.

Almost two weeks after the initial pelleting, an R&DE staff member emailed Hulme residents directly. The email confirmed that the pelleting had taken place and cited the tripping hazard posed by the gopher holes. According to residents, this email was the first statement students received about the poisonings directly from R&DE.

In the same email, R&DE confirmed it had received reports that some blocks were not placed deep enough, but wrote that the contractor had since addressed the issue.

Five residents contacted by The Daily wrote that they had never seen the gophers as a problem in the community. Some residents wrote that they hoped the blocks would be removed, and that there would be systemic changes to address resident concerns. They felt that R&DE had been slow to respond and was out of touch with the interests of the community.

Lindsey Meservey, a fourth-year Ph.D. student in biology and Ryan Meservey’s spouse, told The Daily the poisonings had been “especially heavy and frightening” for students with children. She wrote that in the future, she hoped R&DE would communicate more quickly about their use of chemicals in the courtyard.

“Our children are the most vulnerable of the on-campus population, and we need their safety to be taken much more seriously,” Meservey wrote.

And for now, Tad, the Meserveys’ son, knows to be cautious when playing in the courtyard. He has one question for administrators: “Why did you put the gopher poison there?”