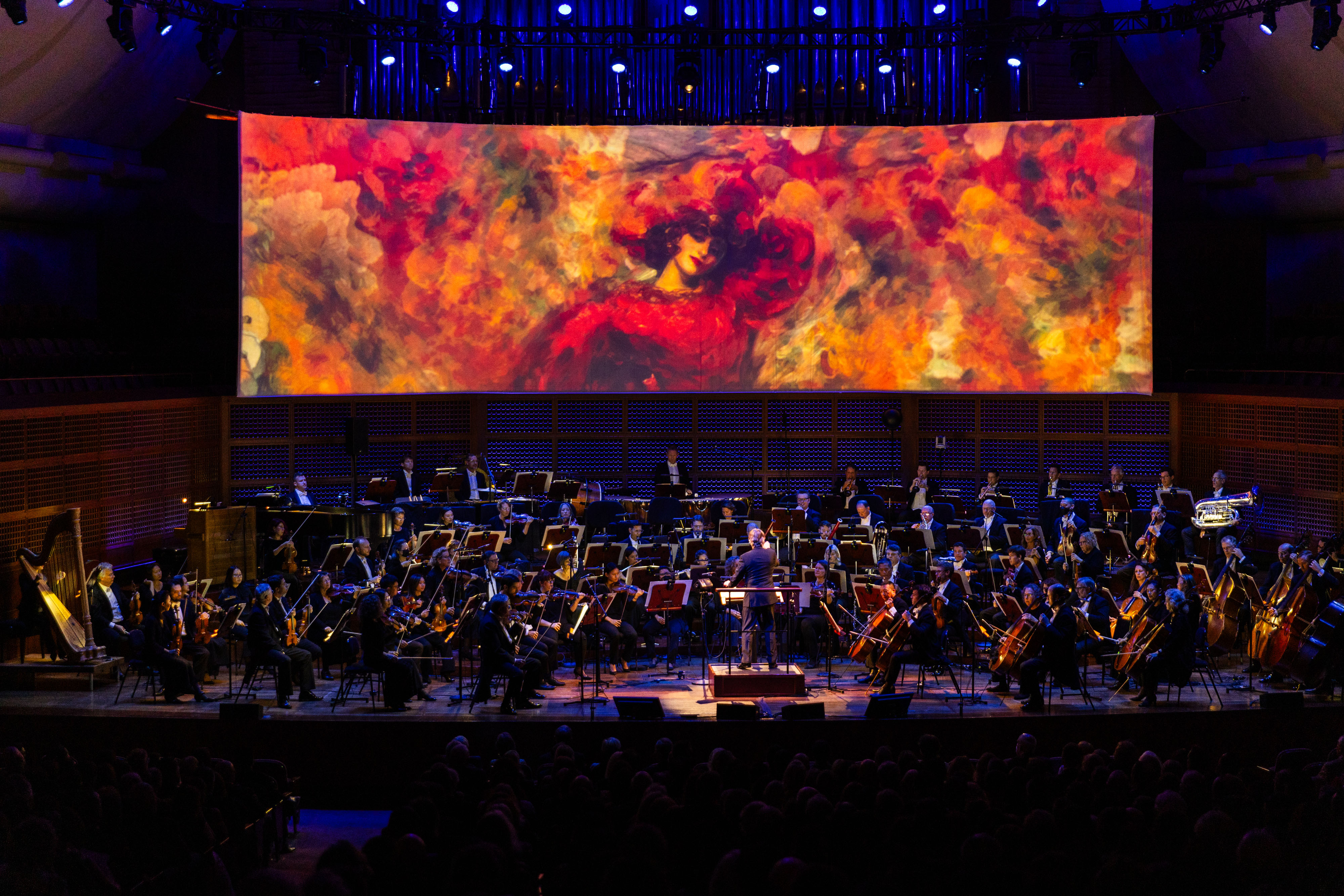

Of all the cultural spaces in the Bay, the concert hall seemed to me the least likely to be affected by the tech world’s biggest fad, generative artificial intelligence (AI). Imagine my surprise when a series of amorphous prompt-generated images began accompanying Strauss’s “Don Juan” in the inaugural concert of the San Francisco Symphony’s (SFS) 2023-2024 season.

Indeed, “imagination” thematized Friday’s performance at Davies Symphony Hall. The program featured AI-generated art and lyrics alongside masterworks by Richard Strauss, Gustav Mahler, Andres Hillborg and Maurice Ravel.

The evening solidified my long-standing dispassion for AI art. While objectively impressive, the generated visuals contributed little to the concert experience. Many images seemed loosely connected at best. A Black woman surrounded by foliage made little sense behind Mahler’s “Songs of a Wayfarer,” a cycle mostly about love, pain and grief; a series of red sculptures distracted Ravel’s “Bolero,” a piece characterized by insistent motion and inspired by dance. If the intention was solely to stimulate the imagination, then not enough consideration was given to the actual audiovisual experience.

Similarly unimpressive was the AI-generated verse of “Rap Notes,” a 21st-century work by the Swedish composer Anders Hillborg. The piece featured local rappers Kev Choice and Anthony “Two-Touch” Veneziale, both of whom delivered impressive freestyles on the rather wholesome prompt of “love, peace and hope.” The fact that Choice had to shoehorn in such mediocre AI-written lyrics genuinely saddened me — it felt like a waste of talent in a work designed specifically to showcase human ingenuity.

At least in the concert hall, it’s apparent that AI art is still artificial. Take a work like “Bolero” — catchy and simple, yet quirky and original. It feels so distinctly human; no modern algorithm could produce such a strange and timeless tune.

In contrast, AI art lies in the uncanny valley, where we feel uncomfortable with images and sounds that are close approximations of humans. Truthfully, I will always judge computer-generated art as if it lies in the uncanny valley; I search for its defects, evidence of its lack of humanity. But when strange and glitchy videos are juxtaposed with masterful classical works, I think it’s objectively obvious where human creativity is actually involved and how valuable it is to the quality of a piece.

Regardless, SFS continues its tradition of remarkable musicianship. All of Strauss’s tone poems are brutally difficult, and “Don Juan” is no exception — still, director Esa-Pekka Salonen delivered a rousing performance. Seated just next to the basses, I could identify details in every section: swirling string undercurrents, indestructible wind homophony, glorious brass fanfares. Especially impressive was their ensemble timing, an essential skill to professional orchestral playing. Musicians synced with millisecond precision from across the stage, accommodating and feeding one another, sometimes against the director’s baton-waving.

Remarkable soloists also stole the show. Baritone Simon Keenlyside’s passion and clarity seemed to carry Mahler’s “Songs” over the orchestral landscape, far beyond the walls of Davies and into the hearts of all in attendance. Soprano Hila Plitmann joined Choice and Veneziale onstage for a cheeky rendition of Mozart’s “Queen of the Night” aria. The three received the most enthusiastic ovation of the night.

SFS will proceed over the next nine months with a typically star-studded concert season. My hope is that this gala concert is a one-off: something poppy that acts more as a novelty than as a bellwether for future programming. The show was unequivocally fun, even if it unintentionally discredited the AI trend. For me, the real takeaway is that the concert hall remains a space where humans can celebrate, without fear or shame, the beauty of their own creations.

Editor’s Note: This article is a review and includes subjective thoughts, opinions and critiques.