Following a collaboration with the Natural Capital Project, based at the Stanford Woods Institute for the Environment, Belize updated its national contributions in 2021 under the Paris Climate Change Agreement and pledged to protect an additional 12,000 hectares of mangroves and restore an additional 4,000 hectares by 2030. Belize already protects 12,827 hectares of mangrove forest, according to the UN.

According to the World Wildlife Fund (WWF), the partnership between Belize and the Natural Capital Project began in 2010. The Natural Capital Project “provides science-based evidence to help resolve conflicts between competing interests and minimize the risks to natural habitats from human activities,” according to the WWF.

Researchers at the Natural Capital Project recently published a model they developed to weigh the environmental and economic tradeoffs of mangrove forest protection and restoration efforts, quantifying the benefits nature provides to society. This model in part led to the ultimate decisions by Belize regarding national contributions and mangrove preservation, according to lead author Katie Arkema. Arkema is now a senior scientist at the Pacific Northwest National Laboratory and jointly appointed at the University of Washington.

According to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, “Mangroves and coastal wetlands annually sequester carbon at a rate ten times greater than mature tropical forests. They also store three to five times more carbon per equivalent area.”

Unlike ordinary forests, mangroves are characterized by “quite rapid growth, and so there is a considerable biomass accumulation,” said Richard Dodd, professor of Environmental Science, Policy & Management at UC Berkeley. This makes them powerful removers of carbon dioxide, as the more biomass accumulated, the more atmospheric carbon is stored in the mangrove forests.

Mangroves are also very vulnerable to harm caused by humans. According to Dodd, “tourism is one human impact that has decimated mangrove forests many places.” A prominent damage caused by tourism is the clearing of mangrove forests for hotels and other development.

Stanford researchers collaborate with governments, communities and development banks and “help them figure out how to quantify the values of ecosystems,” said Executive Director of the Natural Capital Project Mary Ruckelshaus. By making the model free and open source, Ruckelshaus said it can then be used by leaders of other communities to inform environmental policy, too.

“Countries can be as ambitious as they want. But if they aren’t actually able to implement those actions, then it doesn’t really do much good to be ambitious,” said Arkema.

The Paris Climate Agreement set climate goals for nations, and “this paper kind of lays out an approach for setting those targets in a way that’s actually based on science,” Arkema said.

The model was created in collaboration with members of the government of Belize to answer questions about how to maximize economic and ecological benefits of mangrove forests.

“Based on the findings, Belizean policymakers pledged to protect an additional 46 square miles of existing mangroves – bringing the national total under protection to 96 square miles – and to restore 15 square miles of mangroves by 2030,” according to Stanford News.

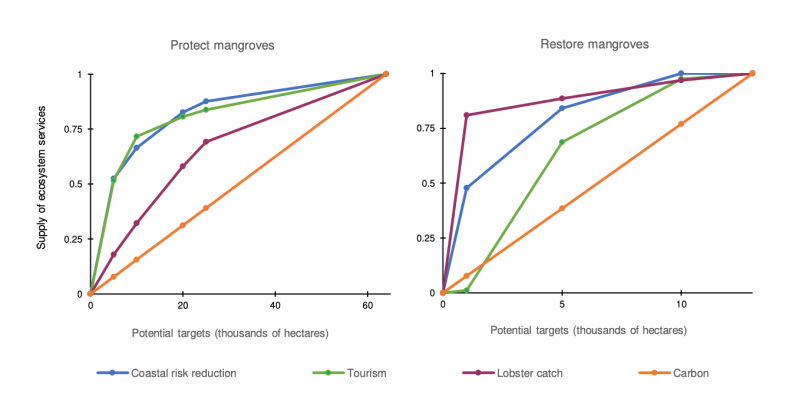

According to Arkema, the project identified four major benefits mangrove forests provide to society: buffering from storms, nursery habitat for fisheries, tourism and carbon sequestration. It also identified optimal locations for mangrove protection or restoration, where societal benefits are maximized, depending on which benefits are prioritized.

Arkema said the model compares the benefits to society with different amounts of mangrove protection and restoration. Some benefits of mangroves, such as tourism, lobster catch and protection from storms come with diminishing returns at a certain point, according to Arkema. “[This] can help us set targets that allow us to balance both these climate goals and also other economic development goals.” In contrast, the benefit of carbon sequestration does not decrease as more mangroves are restored or protected.

The project was a collaboration of people of various backgrounds, including environmental researchers, data scientists and local authorities. Arkema said an important part of her work was connecting leaders in different professions and across disciplines. “There has to be collaboration in order to tackle these big problems.”

In addition, the project took into account the needs of the people it was meant to serve, according to Ruckelshaus, who said the Natural Capital Project worked in a place “only if [they] were invited.”

Rather than this being a limitation on the work they can do, Ruckelshaus sees an opportunity to change minds. “We’re seeing that through our examples that we create in different communities that are willing, then others start to get interested.”