Back in July 2020, when the pandemic was just getting into full swing, the Daily released an opinion by Kiara Bacasen ’22 MS ’22 and Daniella Caluza ’22 summarizing their thoughts about Stanford students living off campus in the Bay Area during the pandemic and online classes. They highlighted how bad the housing crisis in the Bay Area is, and how Stanford students were contributing to it by moving into low-income housing that could have been reserved for local residents. Regardless of whether you were FLI or a person of color—as a Stanford student, that was gentrification at work.

Sadly, Stanford’s online schooling wasn’t the first or last time Stanford students (soon-to-be techies, entrepreneurs, and consultants) would contribute to the displacement of locals in the Bay Area. The housing crisis ravaging America has long been driven by institutions and the wealthy white people who run them. This is something that’s been happening ever since Stanford set roots here, displacing the indigenous Ohlone people. It’s been happening since the destruction of the Fillmore in the 1960s, the subsequent white flight into the suburbs of the East Bay, the creation of BART and its destruction of West Oakland in the early 70s and the restrictive covenants placed around the Bay that made East Palo Alto one of the few places Black people could rent from in the until the 80s. Gentrification really picked up since Google, Facebook and venture capitalists implanted themselves into the Bay Area during the creation of the Silicon Valley and the peak of the dot-com boom in 1999. The effects of this are felt today, with Stanford and tech giants like Facebook still taking part in the housing mess they have contributed towards.

While the definition of gentrification—the “transformation of a poor neighborhood in cities by the process of middle- and upper-income groups buying properties in such neighborhoods and upgrading them”—was coined by Ruth Glass in 1964, it has evolved to mean something much more as the Bay’s housing crisis continues to grow and change. Definitions of gentrification now come with a more complex look at the wealth gap driven by not just the tech industry, but capitalism as a whole.

As someone who was born and raised in the Bay Area, and is now a Stanford student, my personal experience with gentrification and the wealth gap here is a bit more unique. I grew up in Newark, CA, the small suburb directly across the Dumbarton Bridge from East Palo Alto. My parents, both immigrants from Mexico, moved our family here when I was two years old. They enrolled my sister and I in a private Catholic school, since the schools in Newark were terrible at the time. I didn’t really understand that I had a different learning experience from other kids in Newark until I was in 5th or 6th grade, when my soccer teammates told me how Newark Junior High (the only junior high in Newark) was full of teachers who didn’t care and lacked resources for all of the students. All problems of underfunded, POC-majority schools.

I didn’t experience it myself until I went to high school. Newark Memorial High School wasn’t a great school, being half unwilling, half unable to give all their students what they needed. They had some smart kids that “made it out,” either going to four year colleges or finding a good job in tech. But most people didn’t get the attention, money and support they deserved. We were a poorer suburb—nothing like the neighboring cities of Fremont or Palo Alto (just thirty minutes away), where they had extensive infrastructure and stellar high schools. The city didn’t help eithe—six figure jobs in Newark went to city and school administration, all while classroom sizes grew and teachers and counselors were fired. The City of Newark also closed two elementary schools in 2020, citing a budget deficit of $6 million, while simultaneously building a new civic center for city administrators, police department, and library, with a budget of $72.3 million, created out of a sales tax increase. It was here, experiencing all this, that I started to understand how unfair the education and political system was in Newark. Unfortunately, I didn’t know how deep the roots ran. I figured that going into higher education was a way to not only get myself out of this situation, but come back and help my community as well. Stanford was my dream school—ever since my mom worked as a nanny for Stanford professors. Plus, Stanford was my only way of affording a four year university, with its policy to give full tuition scholarships to anyone under $120,000. So when I did get in, with tuition fully paid for, I figured life was going up from there.

Unfortunately, while Stanford came with privileges and opportunities, it also came with socioeconomic discrimination, just by being a Latine from the Bay Area who wasn’t part of the wealthy majority of students. Before I was accepted, my family and I had to move out of our house, since the bank forcibly foreclosed it on us the summer before my junior year. We ended up moving to my dad’s childhood home in North Fair Oaks, an unincorporated area of San Mateo County. With my family there, and me at Stanford, I experienced for myself the enormous wealth gap that exists in the Silicon Valley. The top 10% of Silicon Valley earners hold 75% of its wealth. The average income for the region in 2021 was $170,000, but the average income for service workers in the Silicon Valley was $31,000. Just two street lights away from my home in North Fair Oaks, is one of the wealthiest neighborhood in the United States: Atherton, with a median household income above $250,000, and a median home price of $6.3 million. The admissions, class differences, support systems, student culture, endowment: it was like nothing I had ever experienced in my life. The Peninsula was a whole other place, full of absurdly wealthy people. Stanford contributed to that—having direct ties to not only the Silicon Valley and its tech strongholdings, but political, economic and educational elites worldwide—creating the culture of wealth and elitism that is Stanford’s brand. I would like to note that we are privileged to have not moved out of the Bay Area. My grandparents have had that house since the 80s, and let us rent from them. Without them, we would have been like everyone else—moving to the Central Valley.

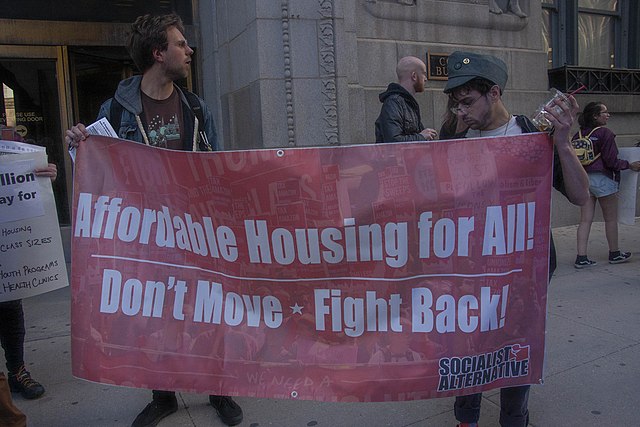

When the pandemic hit, I was filled with even more disrespect for Stanford than I had before, witnessing students gentrifying the Mission and service workers being fired without a second thought. How could the University not protect the very workers that they relied on to keep the school running? Why doesn’t Stanford build subsidized, rent controlled and/or low-income housing for its service workers, instead of having them commute long hours almost every day, with some coming up to 75 miles away from the Central Valley? How was it that students rented out cheaper and low-income housing in the Bay when all the dorms stood empty? I don’t blame students so much—while they are complicit, most are aware of the privileges that they hold from the Stanford name. They shouldn’t be taking rental units, but it’s also not their fault there’s not enough affordable housing, or that Stanford kicked everyone out. I blame Stanford as an institution, and capitalism as a whole. The system, and the institutions that uphold them, are the ones to blame.

This is not simply just a conversation about gentrification. This is a conversation about wealth, and the huge gap between the top 0.1% and the rest of us. So despite my experience growing up in the Bay Area, I don’t think abolishing the tech industry, or putting a ban on “outsiders” is a solution to the issues. The reality is that the tech industry is here to stay in the Bay Area. It’s part of our everyday lives, with iPhones, the internet, computer programs. The Bay Area has always been a place of major commerce, and if we somehow took away the Silicon Valley, another industry will come to replace it. What we do need to do is make things more even. We need those in power (tech companies, political figures, Stanford) to care, and to try. That includes Stanford students, who directly contribute to the wealth gap and housing crisis just by moving into and getting jobs in the Bay. You aren’t the source, but you hold partial blame. You might not be purposefully displacing families, or raising the price of rent yourself or building luxury single family homes or apartments—but you are the market. You are the ones that these companies, these developers, are looking for, to “beautify” and “renovate” the neighborhoods they are “investing in.” I can’t stop you from buying homes and getting good jobs, but hopefully I can make you think about the ripples you are making as you do so.