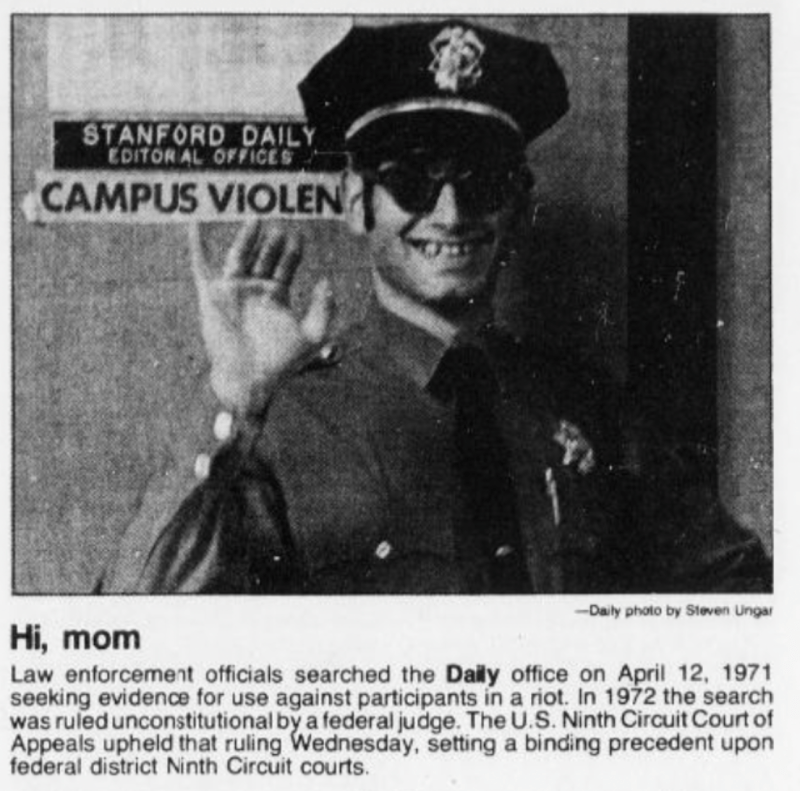

On Monday April 12, 1971, officers of the Palo Alto Police Department raided The Stanford Daily’s office, looking for photographs they believed were in the building. They had entered the office with the goal of finding photos that would incriminate protestors from a violent confrontation a few days prior.

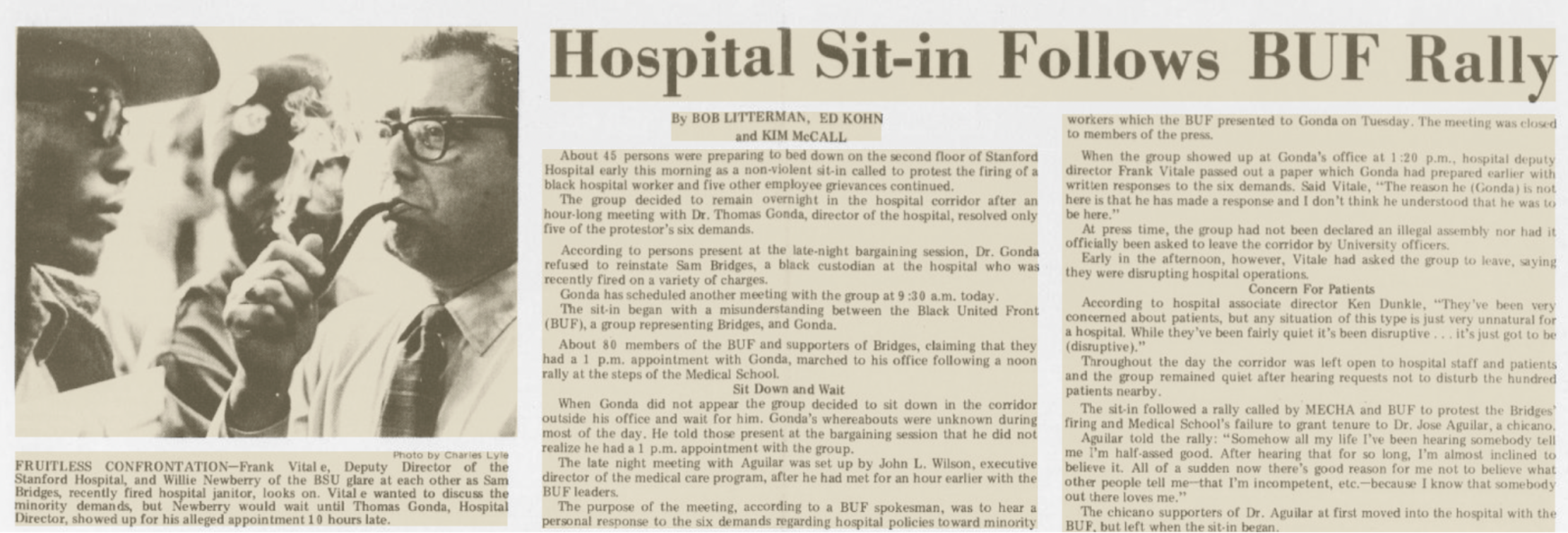

The confrontation involved demonstrators from the Black United Front and the Chicano student group MEChA (Movimiento Estudiantil Chicano de Aztlán) who organized a sit-in at Stanford Medical School. Members of these groups were protesting two incidents that they believed were racially motivated: the firing of a Black hospital janitor and the denial of tenure for a Latino neurosurgeon.

The protestors participated in the sit-in for 30 hours, Felicity Barringer ’72, Editor in Chief of The Daily at the time, recalled. When Stanford eventually called the Santa Clara Sheriff’s Deputies to put an end to the demonstrations, violence ensued. Demonstrators, in anticipation of the police’s arrival, made makeshift clubs out of broken-off table legs with nails on the ends and attacked the police. The Daily’s photographers attended and captured photographs of the event.

13 police officers were hurt, with two sustaining serious injuries, and two dozen demonstrators were either hurt from the clash or while fleeing the hospital from the second floor hallway. Additionally, 23 people were arrested on a number of charges, including assault with a deadly weapon, unlawful assembly and failure to disperse.

In an era of protests during the ’60s and ’70s, The Daily was often the subject of both public anger and acclaim, Barringer explained. Student activists wished for The Daily to become a medium for their protests, and the police sought The Daily’s photographs, which contained incriminating information about protestors.

Students were fearful that The Daily’s photographers were going to send their incriminating photos to the police, or that the photographers at protests were working for, and reporting incriminating photos for, the University’s administration or the police.

Barringer also recalls instances where staffers were demanded to print op-eds as they were written, without editorial overview. Protests outside The Daily building began when the demands were refused.

“There were going to be people who were very angry at us, they could break into our offices, they could break into our windows,” Barringer said. “It was what it was.”

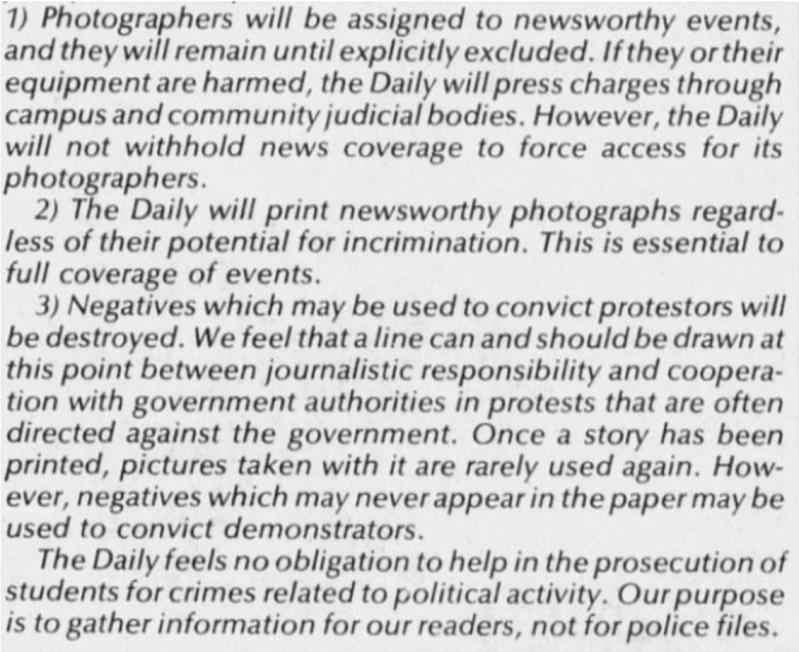

The Daily however, wished to remain a neutral propagator of news. The Daily adopted a policy that safeguarded them from public ire and legal entanglements: they would run any photo they saw as newsworthy regardless of the consequences it may have on individuals. This strategy was adopted a year prior to the sit-in and had become standard practice in many Bay Area papers.

“Photos that we chose not to run, however, we chose not to save because we did not want to be used as evidence gatherers for either the prosecution or the defense,” Barringer said. “This policy led the sheriffs to be sure that we had pictures of the attack on the deputies, and that we were also going to destroy them.”

That Sunday, The Daily printed a special edition with the photos they used and discarded the rest of the photos. On Monday, the police obtained a warrant and raided The Daily office with the goal of obtaining any incriminating photos of the sit-in to identify demonstrators. Although the Palo Alto Police Chief, James Zurcher, did not authorize the raid on The Daily offices, he stood by his officers’ actions to conduct the raid and became the namesake of the Zurcher case.

Barringer remembered going to The Daily office after class that day to find a senior editor waiting for her by the door.

“I couldn’t do anything, they had a search warrant,” the editor quickly told her.

The police had searched their desks, the photo room and every part of the building, but could not find the photographs they were looking for. Whatever photographs that The Daily still had in possession were “moved.” Even Barringer did not know where they were.

Charlie Hoffman ’73 MBA ’76, who eventually succeeded Barringer as Editor in Chief, was in The Daily office when the raid took place.

“Palo Alto Police came diving in late at night,” Hoffman said in an interview with The Daily in November 2017 with Katie Keller ’19. “They were flying through [the files on the desks]. There was paper everywhere.”

“My editors and I got together and said, ‘what the hell do we do,’” Barringer said. “If what is in our offices is essentially open to becoming evidence in court […] we cease to be a journalistic organization and become an information gatherer […] for legal proceedings.”

Gearing up for a legal battle, they reached out to a prominent Stanford law professor at the time, Anthony Amsterdam. The Daily staff talked with the head of the communications department, and the University administration itself lent some support behind The Daily by recognizing the legal ambiguity behind the raid. The team was left to grapple with the decision of whether or not to pursue legal action.

“We felt that all our private sources, all of our notes on our desks, even our friend’s tax return, were violently perceived,” Barringer said. “It was invasive of the journalistic product, because of the possibility of revealing sources, […] even though they didn’t suspect us of having anything to do with the attack itself.”

Amsterdam put The Daily in touch with San Francisco-based lawyers, including Jerry Falk and Robert Mnookin, who carried the case through to the Supreme Court of the United States (SCOTUS). The students, along with the legal team, now had to decide how to approach the case. They believed that the police’s actions may have violated the First and Fourth Amendments. But success wasn’t guaranteed.

“My first reaction… was that it was outrageous, that they never would have done to The San Francisco Chronicle, much less The New York Times, what they did to The Daily,” Falk said in Keller’s article. He remembers thinking that they “had a winning case for a subpoena-first rule.”

Mnookin, however, was more doubtful. “I was offended by what [the police] had done, but I did not think it would be an easy case.”

The team filed a suit in May 1971 and won in the United States District Court for the Northern District of California, where the court adopted all of The Daily’s claim.

“The court told the police, ‘If you need the evidence, get it someplace else,’” Barringer said.

The police department appealed the decision, but the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit affirmed the district court’s decision to side with The Daily. Additionally, the appellate court charged the police with The Daily’s attorney fees, which were in part accrued with donations. This became an important factor in SCOTUS’ later ruling against the Daily.

“The appellate decision embraced the idea that infringing on the press’ ability to do its job, and giving them fear that by doing their job they may be called into court was totally against First Amendment protections,” Barringer said.

The verdict was overwhelmingly in The Daily’s favor, which led the Supreme Court to pick up the case. The Stanford Daily community, as well as the press community at large, held their breath.

In a Jan. 1978 interview with The Daily, months before the Supreme Court decision, Zurcher himself commented on the case.

When asked his thoughts about the Supreme Court’s possible reversal of the lower courts’ decision, he said, “I recognize the First Amendment problem and I truly understand what newspapers have to do. I would certainly give a lot of thought to any third-party searches in the future.”

The petitioners, led by Zurcher, had believed that there should be no additional requirement beyond probable cause for the police to obtain a search warrant against The Daily and that they had operated in conduct with existing laws.

Steven Ungar Ph.D. ’72, a Daily editor who was also one of the infamous photographers at the time of the raid, had said that he was “optimistic” and believed in the power of the First Amendment.

Fred Mann ’72, a managing editor at The Daily at the time of the raid and one of the plaintiffs of the case said in a January 1978 interview, “I’m happy being there, before the Supreme Court, but realistically, with the makeup of the court, it’s not very favorable for us.”

On May 31st, 1978, the Supreme Court ruled against The Stanford Daily in a 5-3 decision. They held that the police reserved the right to search any newsroom when the warrants were approved by a court, and that such searches did not violate the Fourth Amendment. The majority argued that The Daily’s insistence on the police needing a subpoena, as opposed to a warrant, could only result in a disappearance of the evidence in question.

“A search warrant allows police officers to ransack the files of a newspaper, reading each and every document until they have found the one name in the warrant,” wrote Justice Byron White in the majority opinion.

Justice Potter Stewart sided with The Daily. “Policemen occupying a newsroom and searching it thoroughly for what may be an extended period of time will inevitably interrupt its normal operations,” he wrote in the dissenting opinion. “Protection of those sources is necessary to ensure that the press can fulfill its constitutionally designated function of informing the public.”

Additionally, Stewart believed that protection of documents goes beyond news organizations.

“Countless law abiding citizens – doctors, lawyers, merchants, customers, bystanders – may have documents in their possession that relate to an ongoing criminal investigation,” he said. “The consequences of subjecting this large category of persons to unannounced police searches are extremely serious.”

Bob Percival JD ’76 AM ’78, who clerked for White in 1978 and became very familiar with White’s perspective on cases like Zurcher, said in Keller’s Daily article that “some [justices] thought, ‘Well, it’s only reasonable that if there’s evidence showing who those [protestors] were, [the police] should be able to find it’ — especially since they went to the magistrate and were authorized to search.”

He further explained that the justices in the majority were concerned with the appellate court’s award of attorney’s fees against the police, a precedent that they believed might inhibit police from trying to enforce the law.

“The police seemed to have conducted themselves very well. They didn’t mess up the offices of The Daily, they put everything back, they didn’t find anything,” Percival said. “The justices thought this [was] kind of an overreach to punish the police for what they, in good faith, thought was lawful behavior and when they acted reasonably.”

Then-former Daily staffers found this decision horrifying. The case had set a precedent against journalistic privacy.

Margie Freivogel ’71, who preceded Barringer as Editor in Chief, recalled the reaction of the staff: “Oh Gosh, what have we done?”

“The last thing we wanted was a judicial decision to the negative on this issue,” said Hoffman.

Following the court’s decision, and a national outcry from the public and large media organizations, then-President Jimmy Carter asked Congress in April 1979 to reach a legislative solution to the issues raised in Zurcher v. Stanford Daily.

Some members of the public believed that the Palo Alto Police Department had acted wrongly in the raid of the office, while others believed that the injury of the 13 officers at Stanford hospital warranted the raid to punish the attackers.

A Los Angeles Times editorial from the time said, “The U.S. Supreme Court has taken a narrow, crabbed, suspicious view of the First Amendment and has given exuberant, indulgent, and trustful approval to a sharp extension of police power.”

Howard K. Smith, a renowned reporter of ABC News, called the Zurcher decision, “the worst, most dangerous ruling the Court has made in memory.”

Jack C. Landau, a renowned journalist, attorney, and free speech activist, spoke before the Senate Committee on the Judiciary, Subcommittee on the Constitution, and said the Zurcher decision granted the police a power “alien” to American free society.

Congressional reactions to the court decision began while the case was being processed in the Supreme Court, and hearings in committees related to press freedoms were held in the House and Senate almost immediately.

Additionally, in October 1978, the Supreme Court rejected a request for a rehearing of the 31st verdict.

A year after the court decision, Congress passed The Privacy Protection Act of 1980, which supplemented the Fourth Amendment and increased privacy protections for the press. It established what the district and appellate courts suggested in the Zurcher case: the requirement of a subpoena by the police in order to search newsrooms.

Despite the ultimate success of The Daily’s efforts embodied by the legislation, today some lawyers believe that applications of the Privacy Protection Act have become increasingly more difficult. The wording of the act, specifying that it defends “those who disseminate information to the public,” has become much broader today than it was four decades ago. The information age has fundamentally changed what journalism looks like.

Elizabeth Uzelac, a former assistant attorney general for the Oregon Department of Justice, raised an emblematic question in a Northwestern Law Review publication: would courts recognize at-home bloggers as information disseminators?

Courts have successfully avoided applying the act in cases relating to computing environments. Law enforcement has been able to seize laptops, phones and servers without a subpoena, and there does not appear to be a legal remedy for this unforeseeable technological development in sight. Today, anyone can be a journalist – anyone can be a mass disseminator of information online.

Despite the relative gravity of the case, many Stanford undergraduates remain unaware of this piece of Stanford history.

Elijah Schacter ’25 said that he had never heard of the case. However, he found the intricacies of the case fascinating.

“Between the First and Fourth Amendment arguments, the stark differences in the opinions of the lower courts and the Supreme Court, and the general political culture in the U.S. at the time, there’s a lot of really interesting things here,” Schacter said.

“The passage of the Privacy Protection Act just two years later shows how The Stanford Daily participated in such an important case,” he said. “I’m glad that they eventually got the ability to protect the process. They won in the end.”

This case reminded Emily Winn ’25 of Berkeley’s infamous protest culture of that era. She is proud of The Daily’s history and her newfound knowledge of its own protest culture.

“It shows how student journalism is so valuable for multiple reasons,” she said.

Dylan Rivera ’24, agreed with Schacter and Winn. “The fact that the case inspired the Privacy Protection Act of 1980 legitimizes The Daily, and other college newspapers, as a crucial cornerstone of [their] communities and shows they shouldn’t be disregarded just because they’re run by college students,” he said.

Samiya Rana ’25 said, “This has made The Daily way cooler and more badass.”

Barringer emphasized the beauty of this case. She said that over the nine years between the raid and the Congressional Act, countless Daily editors and staffers worked on this case — both on the legal minutiae and on fundraising for legal costs — all while being full-time students and working for The Daily. It stands as a symbol of the power of student journalism and The Stanford Daily.

“I can’t help but have pride in what we did,” she said.

A previous version of this article misspelled Margie Freivogel’s name. The Daily regrets this error.