A prominent research journal has confirmed to The Daily that it is reviewing a paper co-authored by University President Marc Tessier-Lavigne for scientific misconduct following public allegations that the research contains multiple altered images.

Three other papers published in Science and Nature by the University president also contain “serious problems,” according to Elisabeth Bik, a biologist and science misconduct investigator routinely featured in outlets such as The New York Times, The New Yorker and Nature, who was contacted by The Daily last month to review several separate allegations. Tessier-Lavigne is the lead author on two of these papers.

Bik’s suspicions of manipulated imagery were corroborated independently in interviews by The Daily with two other misconduct researchers who reviewed the papers. Allegations regarding these four papers and multiple others have been made repeatedly over the last seven years on PubPeer, a site that allows scientists to identify suspected anomalies in publications.

The University acknowledged “issues” in the papers but downplayed Tessier-Lavigne’s role in the potential misconduct in a statement Monday night.

Spokesperson Dee Mostofi wrote Tessier-Lavigne “was not involved in any way in the generation or presentation of the panels that have been queried” in two of the papers, including the paper under review, which was published in The European Molecular Biology Organization (EMBO) Journal. Of the other two, the University wrote that the issues “do not affect the data, results or interpretation of the papers.”

Bik, though, disagreed with the University’s assertion that the “mistakes” do not impact the scientific integrity of the papers. “I do not agree with [the] statement that these issues have no bearing on the data or the results,” Bik wrote The Daily in an email Monday night.

“I hope that Dr. Tessier-Lavigne will not brush off these concerns as irrelevant. There appear to be a lot of visible errors in these papers, and some duplications are suggestive [of] an intention to mislead,” she wrote. “Dismissing these as not affecting the data is not very reassuring. The reader might wonder how many non-visible errors might be present in other parts of the data.”

Tessier-Lavigne did not respond directly to a request for comment.

According to the University’s statement, Tessier-Lavigne was made aware of several errors in his papers in late 2015, at the same time as he was being considered for the role of University president. “The same day in 2015 that President Tessier-Lavigne was alerted to the issues, he in turn alerted editors at the two journals about the three papers,” Mostofi wrote. She did not respond when asked how Tessier-Lavigne was alerted.

Mostofi wrote that Tessier-Lavigne voluntarily submitted corrections to Science that were not published. The University and Tessier-Lavigne did not explain why the corrections were not published, and The Daily has requested copies of the proposed corrections.

The Daily reached out to Science and Nature, where another of Tessier-Lavigne’s papers containing alleged data alteration was published, for comment. Science’s editor-in-chief Holden Thorp wrote in an email that he would “check around.”

The investigation underway

The EMBO Journal wrote in a public post last week that it is reviewing the allegations regarding a 2008 paper about receptors within the brain for which Tessier-Lavigne is listed as the third author of 11. “The EMBO Journal is aware of these issues and is looking into this,” the journal wrote. Facundo Batista, EMBO’s editor-in-chief, confirmed the investigation in emails with The Daily, writing that the journal has already “evaluated” the issues raised on PubPeer and “as a consequence” is “currently engaged in a full due diligence screen.”

Since 2011, EMBO has employed a data integrity analyst, who analyzes all papers before publication. Public allegations first raised on PubPeer in 2018 have brought the 2008 paper to EMBO’s attention.

The public acknowledgement marks a rare step for EMBO, which is regularly rated among the top journals of its field by Scimago Journal Rankings and receives almost 3,000 submissions per year. The journal has retracted papers based on PubPeer allegations without first publicly acknowledging an ongoing investigation.

A public announcement likely means the paper has been under investigation for some time, said a researcher with direct knowledge of journal investigation processes who spoke on the condition of anonymity because of the sensitivity of the allegations.

When asked about the specific allegations and the timeframe of the investigation, Batista wrote, “We currently cannot comment more substantively before we have a better assessment of the full situation.”

It is unclear how long the review will take, and allegations can go without a response from the journal or authors for years. But an investigation could carry serious consequences for Tessier-Lavigne even if he is absolved of the alleged manipulation or other direct wrongdoing.

Silvia Bulfone-Paus, a prominent German researcher, was forced to step down as the director of the Borstel Institute in 2011 after image manipulation was found in several of her papers (Bulfone-Paus blamed two of her post-doc researchers). Carlo Croce, an Ohio State University professor, was beset with similar allegations in 2017 — an official review conducted by the university found earlier this year that he had not manipulated imagery himself, but the professor was disciplined over “management problems,” and two of his researchers, who were determined to have made the falsifications, were dismissed. And Gregg Semenza, a Nobel-prize-winning scientist, retracted 17 papers after allegations were made on PubPeer.

Tessier-Lavigne’s papers with issues confirmed by the University have accrued tens of thousands of downloads and include some of his most cited work in neurobiology. None of the papers has been retracted or corrected.

Tessier-Lavigne’s work in the nineties was the first to identify the molecule required for guiding axons, the strands which connect neurons in the brain, opening up a new field of research. Prior to taking on Stanford’s presidency in early 2016, Tessier-Lavigne directed more than a thousand scientists at biotechnology companies Genentech as well as Regeneron. Tessier-Lavigne’s salary at Regeneron in 2014 was $1,764,032, according to a previously-unreported class action lawsuit alleging excessive compensation for members of the Compensation Committee, which included Tessier-Lavigne. It was later settled. He earned $1,555,296 from Stanford in 2021 with an additional $700,000 annually as a board director for Regeneron.

Scientific journals and institutions have historically been reluctant to investigate alleged misconduct, particularly by powerful scientists, experts say.

“Unfortunately, many scientific journals and academic institutions are slow to respond to evidence of image manipulation,” Bik wrote in a New York Times op-ed earlier this year.

And even when they do respond, journal investigations are slow, bureaucratic and often entirely confidential, according to several researchers with knowledge of the retraction process.

Data manipulation repeatedly alleged

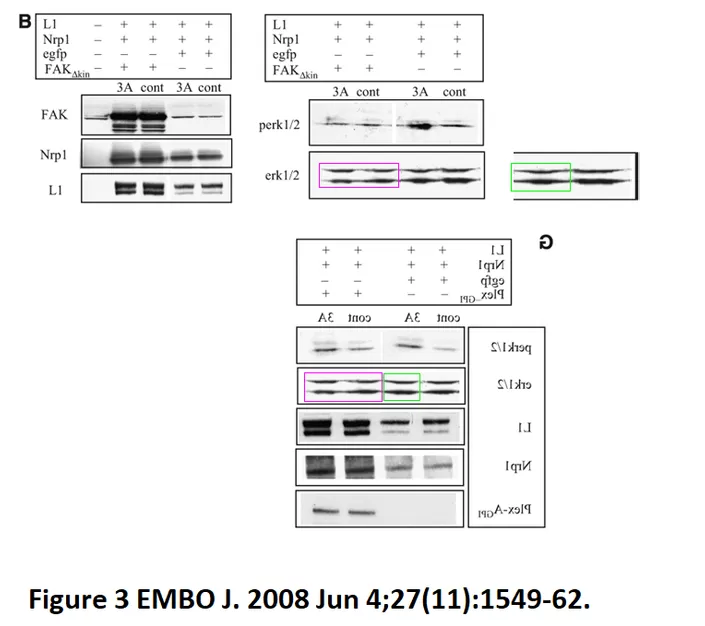

The paper under investigation by EMBO is one Bik had voiced concerns about to The Daily in an email last month before the review became public. She wrote the paper has “several problems of concern,” (her emphasis). In her view, this suggested “an intention to mislead,” Bik later told The Daily in an interview, relying on her experience of investigating more than 20,000 papers for research misconduct and causing nearly 1,000 retractions and roughly the same number of corrections to make that claim.

As third author on the EMBO paper, “President Tessier-Lavigne was included solely to recognize his contribution in providing necessary reagents for the research by other authors,” the University wrote in its statement Monday night.

Co-authorship typically implies more direct involvement. At Yale, for example, a co-author in scholarly publications should be “directly involved in … writing a draft of the article” and must “review and approve the manuscript before it is submitted for publication,” according to university guidance.

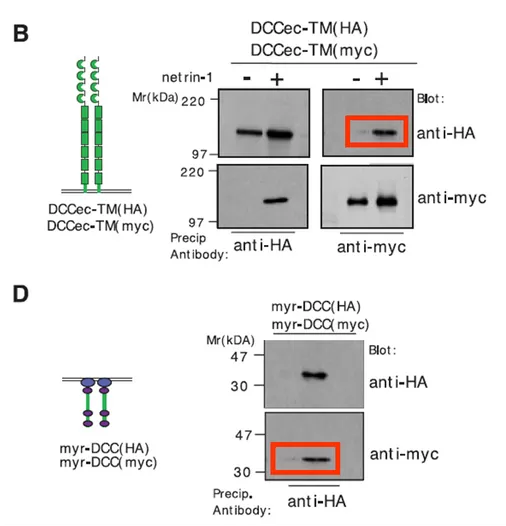

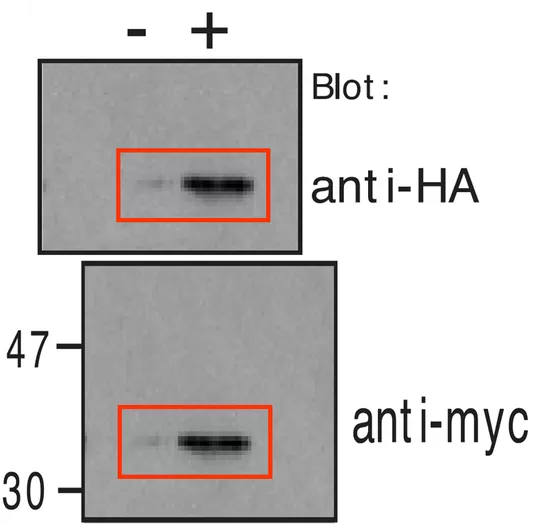

The concerns Bik says she observed in the EMBO paper range in complexity. For example, one of the panels in a figure appeared to have been copied directly and in its entirety from another panel. This is what she called a type one error — one she said is most commonly a typesetting error, or an accidental error made when assembling the photo.

But other instances of alleged manipulation are more intricate. In a different figure, Bik said that a gel band appeared to have been copied and flipped around within the panel. This, she said, is a type three duplication — one within the same panel with alteration that may be designed to allay suspicion of manipulation.

The University and Tessier-Lavigne did not respond to questions regarding specific concerns about the paper. “Questions regarding these data should be addressed to the lead (corresponding) authors,” the University wrote.

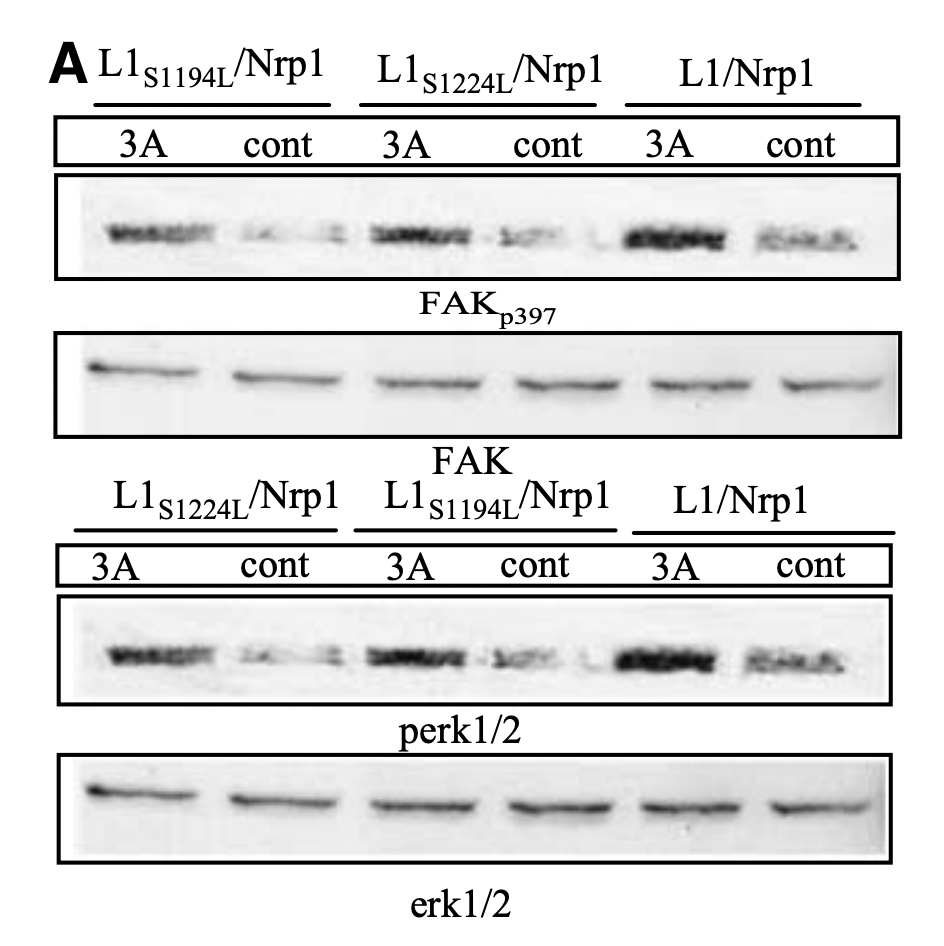

A 2001 study for which Tessier-Lavigne is the lead author with just one other researcher has more than 700 citations — a towering amount in a field where most papers scarcely get ten. According to Bik, this paper, which was published in the prestigious journal Science, contains figures with image alteration. “The photoshopping was done intentionally, there’s no way around it,” said Bik in an interview with The Daily after examining the areas surrounding gel bands for patterns and with forensic tools, though she added the motivation was unclear and could have been something other than falsification.

The University wrote that, “The origin of the tiling and of the partial overlaps is unknown but may have occurred during transfer of images to the journal.”

In several places, gel bands seem to show duplication within images — Bik said this could be a way to avoid showing certain results. The University disagreed, saying, “These mistakes also do not affect results or interpretation.” One of the research misconduct experts who reviewed figures for The Daily but spoke on the condition of anonymity in light of the sensitivity of the allegations said in response that Tessier-Lavigne “should produce the original materials to support that claim.” Neither the University nor Tessier-Lavigne responded to The Daily’s request for such evidence.

More concerning to Bik, she said, are two images within the paper that purport to show an axon at two different points in growth. But the second image appears to be a shifted version of the first. “It seems to have been done intentionally,” Bik said.

“Because the way the image is shown, it makes it look like [the axon] grew a little bit more. While if you look at the little dots,” Bik said, pointing at the artifacts which led her to question the image “you can see it just didn’t grow.”

The University called this “an incorrect duplication of a micrograph.” Neither the University nor Tessier-Lavigne responded to a question asking how such a duplication could have occurred.

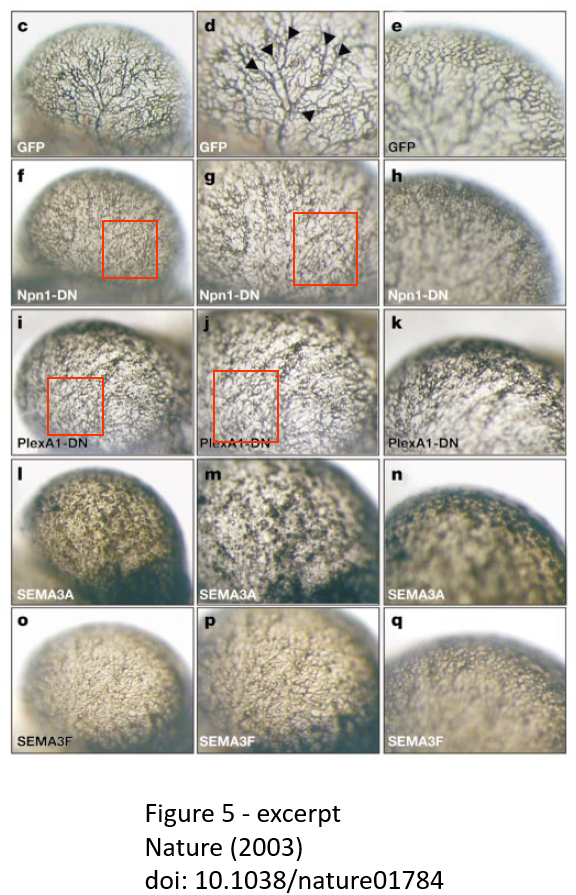

Another paper, published in Nature in 2003 with Tessier-Lavigne listed as the fourth of 14 authors, contains a series of images characterized as different from each other. But according to Bik, they appear to actually be the same image, simply rotated. “The rotation could suggest that there might have been an intention to mislead,” Bik said. This is one of the papers over which the University claimed Tessier-Lavigne had no direct oversight of figures.

A fourth paper, also published in Science with Tessier-Lavigne as the lead author, appears to show a reused pair of gel bands, according to Bik. The University did not respond to questions about this allegation.

Bik and the other research misconduct experts who spoke on the condition of anonymity concurred that proving intentional malice from published papers is near impossible without the completion of a formal review. Ferric Fang, a prominent neurobiologist who has also served as the editor-in-chief of scientific journal Infection and Immunity, wrote in an email to The Daily that he agreed with Bik that several of the figures in the four papers “look problematic.”

“I am not saying that all of these image problems are innocent— just that it is not possible to…assign responsibility without a more formal inquiry and an examination of the primary data,” Fang wrote. “I cannot say more than that.”

Experts told The Daily that the original data from older papers is often discarded, making it impossible to compare potentially altered images with originals and determine full responsibility.

A previous version of this article contained copy errors in which an axon was incorrectly referred to as a netrin, The EMBO Journal’s unabbreviated name was misstated and a screenshot was incorrectly attributed. The Daily regrets these errors.

This article has been updated to include comment from The EMBO Journal.