In the first edition of Stanford Film Study, we went over one of Stanford’s staple running plays, power. This edition will go over a closely-related concept: counter. Counter looks very similar to power at first glance, as both concepts utilize down blocks and a pulling guard. But counter has a dimension of disguise that can make defenses overflow to one side of the field.

How does counter work?

Counter attempts to open a gap to the outside of an offensive tackle or tight end. Similar to when they call power, the Cardinal try running counter out of heavier personnel groups on the field. Sometimes this will be in sets with an in-line tight end and other times it will be with extra offensive linemen. This creates uncertainty within the defense about which gap Stanford is trying to open.

When the ball is snapped, all but two offensive linemen will apply down blocks away from the playside. The strong side tackle will double team with the right guard, and then try to make his way to the weak side linebacker. The fullback pretends he’s blocking toward the weak side, but then goes and blocks playside. This maneuver can effectively disguise the counter play as a zone concept and make it look like the running back will go toward the weak side.

Meanwhile, the pulling guard will come around and seal the edge, which is a role the fullback performs during power. The fullback then becomes the main blocker in the gap between the tackle and guard. He engages the first defender that comes through that gap, similar to what the guard does in power.

However, when the pulling guard leaves, there’s a gap left open for defenders to attack. To deal with this, the weak side tackle will perform a gap-hinge block. A gap-hinge block is when an offensive lineman steps to the interior to prevent inside penetration. If no defender engages with the lineman, he will then shove the outside defender upfield, away from the play side. Sometimes when there’s an inside penetrator and an outside defender, the weak side tackle will try to perform both functions.

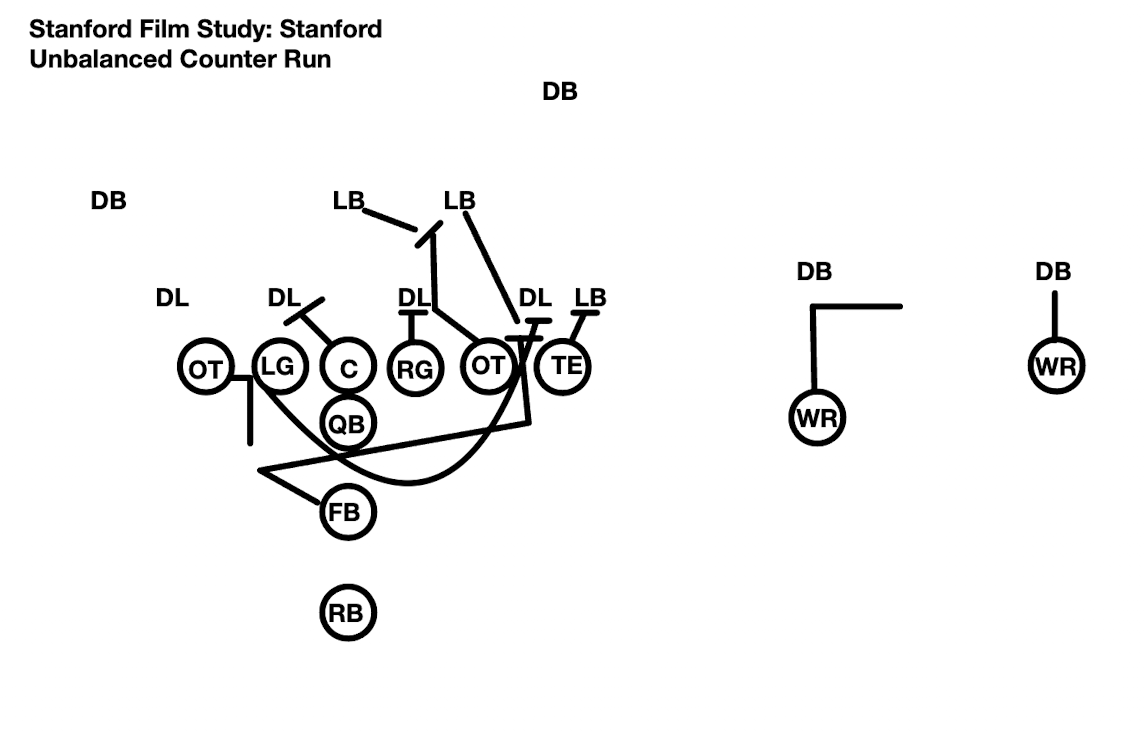

Below is a diagram of counter against Cal’s 4-3 defense in 2015. On this play, Cal has an overhang linebacker lined up a shade outside of the tight end. There are two defensive backs lined up against the two receivers to the outside. There’s also one safety over the top and one safety lined up on the weak side, at the same depth as the linebackers.

Once the ball is snapped, quarterback Kevin Hogan ‘15 turns over his left shoulder, making it seem like the play is going left. But then Hogan hands it off to star running back Christian McCaffrey ‘18 on the right. The guard is able to seal the edge defender, who comes crashing down. Then the fullback engages the front-side linebacker. The strong side tackle is able to make his way up to the backside linebacker, although the linebacker is able to avoid his block. Luckily for the tackle, the linebacker overshoots the gap, which takes him out of the play.

From there, McCaffrey is able to use his speed to outrun the weak side safety and pick up a 20+ yard gain.

Stanford head coach David Shaw still likes to use fullbacks and heavier personnel in his offensive packages. Stanford could use counter to play off their zone running game later in the season. However, the offensive line will have to continually improve at applying down blocks and communicating on double teams, or else the play will stall out.