Death, taxes and catalytic converter thefts. At Stanford, it is a near-certainty that community members will at some point receive an AlertSU sharing news that a catalytic converter has been stolen. Between February and March of this year, 11 such thefts were reported to the Stanford University Department of Public Safety (SUDPS).

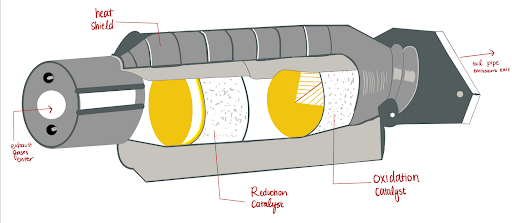

Catalytic converters are located on a car’s undercarriage right behind the front wheels, making them a relatively easy car part to steal. Catalytic converters help car manufacturers comply with the Environmental Protection Agency’s (EPA) stringent regulations on fuel emissions, turning toxins into less harmful gasses like water vapor and carbon dioxide. Worth between $300-2500 in new condition, the installation of catalytic converters has been required in all United States cars since 1975.

Why the interest in catalytic converters specifically, though?

According to assistant professor of chemical engineering Matteo Cargnello, the most important components of catalytic converters are these three precious metals: platinum, palladium and rhodium.

“If you think that gold is precious, then imagine something that is 10 times more expensive than gold, and there’s quite a bit of that in the catalytic converter,” Cargnello said. “That’s what makes it appealing for people to steal them now.”

It is these precious metals that help facilitate the chemical conversions to turn very harmful byproducts into something much more harmless. There is significant interest surrounding these metals specifically because of how effectively they convert toxic pollutants produced from car engines. They are also stable elements, unlikely to be affected by other components found in gasoline.

“Catalytic converters take in the toxic gases produced in cars’ internal combustion engines, and using a catalyst along with oxygen and hydrogen atoms from the air, they split up these harmful gasses into carbon dioxide, nitrogen gas and oxygen,” said Shiley Einav ’24, who studies mechanical engineering and works on the Stanford Solar Car Project.

Burglars typically target catalytic converters for the trace amounts of valuable metals like platinum and rhodium used to help purify the car’s emissions. The cost per ounce of precious metals has skyrocketed over the years due to scarcity, the intricate extraction process and general demand for commodities like jewelry and microelectronics. When sold to a recycling facility, resellers can rake in $50 to $250 per part.

“Up to 10 to 15 years ago, there was no interest in recycling those materials, and now some of these metals have become so expensive and there’s more of an incentive to that,” Cargnello explained. “The sad part is that that’s what makes it also appealing to thieves. Those materials can be recovered, although you need very specialized operations in order to do that.”

Although cars can still technically run without a catalytic converter, it is illegal to drive without one. Additionally, such cars would contribute high levels of dangerous emissions into the atmosphere.

According to Bill Larson, SUDPS’s Public Information Officer, catalytic converters are “exposed underneath most vehicles as part of the muffler,” and are “either cut off or unbolted.”

Though thefts have been reported across vehicle types, Toyota Priuses tend to be targeted because their catalytic converters contain more precious metals to optimize for the hybrid power system of an electric battery and combustion engine.

The preference has been reflected on campus — SUDPS records show that an overwhelming majority of thefts are reportedly from Toyota Priuses. On campus, theft hotspots include parking garages such as the Wilbur Field Garage and the Stock Farm Garage.

Until more car companies and manufacturers can shift toward a more protective design that can lock or prevent the easy removal of catalytic converters, it is unlikely that the issue of catalytic converter theft will disappear anytime soon.

Still, there are strategies that car owners can use to protect against theft — owners can “buy and install a metal cage to go around the converter or [weld] it to the frame of the vehicle,” Einav said.

Fortunately, researchers like Cargnello are working toward finding alternative solutions for reducing the need for high concentrations of precious metals by a significant amount.