The sound of a man’s steady tenor voice fills the theater.

“This is how to make time to think: break yourself into pieces, scatter them, label them anything other than a name, toss to others and their offspring in the road.”

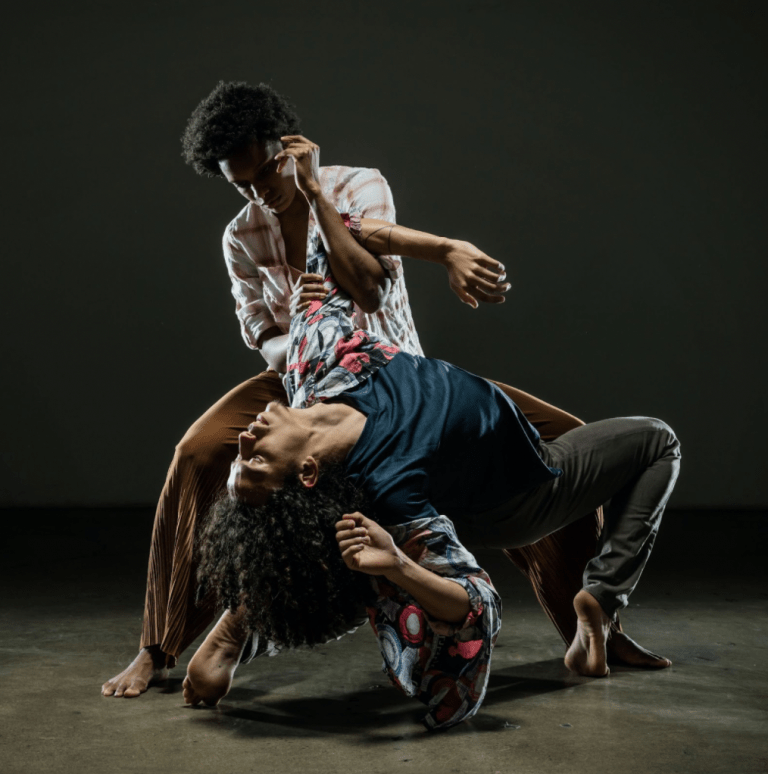

His voice moves along the poem like a determined climber scaling a mountain, inflection sure and subtly rhythmic. On a spacious stage, some half dozen dancers move to this phantom of a melody. Their gestures are impressive enough on their own — each a plain testament to years of discipline — but when paired with the voice overhead, the performance takes on a mesmerizing quality.

This is Kin, a contemporary dance company founded and directed by former Stanford faculty member Robert Moses. The group of thirteen dancers, including three guest artists, started by performing excerpts from Kin’s 2019 project “The Exceptionally Elderly Overweight Black Man Phoenix.” They also debuted Moses’ 2022 show, “The Soft Solace of a Slightly Descended Lost Life (Suck It),” an interdisciplinary work featuring choreography and spoken word poetry based on his experience as a Black man in the United States — specifically, the “fractured heritage, risk and theft of solace and safety from everyday life.” For most of the 90-minute program, half a dozen dancers occupied the stage. Often, they were split into a featured duet with a group of background performers. The event was hosted at the newly-renovated Presidio Theater in San Francisco.

The opening of “Solace,” the new project, carried a palpable sense of danger, from the “Jaws”-esque pounding of the piano in the audio track, to the choreography’s frenetic pacing and angular shapes. The dancers embodied unease through their splayed fingers; shaking, ranging from tremors in the hands to full-body convulsion; the quick, spilling quality of their masterfully-controlled rolls. The spoken word poetry, which was written by Moses, voiced anger at Moses’ experiences of marginalization, especially the trauma of police brutality for Black Americans.

Scattered throughout the stage were suspended sculptural installations. Each jellyfish-like structure consisted of many long translucent ropes hanging from a square plane several feet above the stage.

At times, the choreography was syncopated: each of the several dancers executed unique choreography in a contained individual kinesphere. Elaborate duets involving lifts and other partner moves were scattered throughout the performance. They felt like the rare moments of synchronization between two broken clocks. Some made use of the sculpture installations: for instance, one partner watched kneeling, as if entranced, while the other fervently shook the threads of the installation before them. These duets, too, served to reinforce the voiceover. Trust falls, embraces and comforting gestures mirrored themes of kinship and community. In one such instance, the voiceover articulated Moses’s worry for his son in encounters with police, as well as frustration with “the talk” that Black parents often give their children about how to behave around law enforcement.

During his time at Stanford, Moses held positions as artist-in-residence and director of the Committee on Black Performing Arts. He worked on campus for a total of 21 years.

“The spirit with which the faculty institution wants to engage with the students is fantastic,” Moses cited as his favorite part of his time at Stanford. “The most important thing to the faculty and the administration, as far as I could tell, is the students.”

Parts of the weekend’s show tackled the ups and downs of the artistic process. In “Solace,” dancers Vincent Chavez and Jenelle Gaerlan engaged in a dynamic duet, moving through opposite level changes to each other — as one jumped high, the other would spin low onto the floor. Moses detailed the stress of chasing authentic artistic expression in the voiceover: “The dances are real, my feelings are real, and the ideas are sons of bitches that become living, breathing lovers you need to, but can’t face when they’re staring you in the eye.”

Excerpts from “Phoenix” also dealt with the demands of the artistic process. The spoken word soundtrack consisted of intimate sensory descriptions of life as a dancer, highlighting the ever-present mission to perfect their craft. On the stage, a single dancer retraced the same path and executed the same demi plie and starfish poses, embodying this never-ending quest for refinement.

Motifs were similarly embedded throughout “Solace” as well. Each dancer seemed to embody their own unique style — for instance, developing through the limbs in characteristic languorous, liquid motions. In a question-and-answer session following the performance, Moses explained that this was indeed intentional. These styles provided “a way of moving in and out of the individual,” differentiating their solos from ensemble moments.

Last weekend marked Kin’s return to the stage after the pandemic forced a live performance hiatus. Dancer Crystaldawn Bell expressed joy about “being back in the theater,” saying, “I was curious if people would feel comfortable showing up again and the support was overwhelming.”

Fellow company member Emily Hansel echoed her sentiments and added that they felt increasingly settled within the choreography with each performance.

“Each time we do it is different and exciting in a new way,” they said. Hansel has been in the company since 2019. They were asked to revisit excerpts from 2019’s show, “Phoenix,” for this return performance. Despite the material being older, they found the return surprisingly natural: “It felt very at home.”

Robert Moses’s Kin proved the effectiveness of movement as a mode of communication. In a synthesis of word and gesture — sound, sight and sensation — Moses created a visceral language to make sense of his lived experience. The choreography acted as a needed reference point for Moses’s elaborate spoken word piece; it was as if the dancers’ actions narrated his words, not the other way around. Indeed, they were portraying experiences distinctly tied to the body. The body is a site for the plight of the perfectionist dancer and the trauma of racial violence alike. Kin is a living, breathing memoir of Moses’ lived experience, from actor to subject.

Editor’s Note: This article is a review and contains subjective opinions, thoughts and critiques.