Two girls, Mona and Tamsin, kiss in a pond. Slowly, Mona’s hands inch from Tamsin’s face to her neck — what seems like a murder begins. Mona shoves Tamsin underwater, strangling her. Tamsin’s breath bubbles as she kicks and claws. Her eyes, wide with fear, plead from underwater. A few moments pass. But wait — before too long, Mona releases Tamsin and she rapidly climbs out of the abscess. “What the fuck are you doing?” Tamsin yells as she resurfaces, hoarse and sputtering, “You crazy fucking bitch!” Mona is already gone, though, stalking away to the triumphant waltzing roar of Edith Piaf’s “La Foule.” She is confident. We cannot help feeling respect for her. The credits roll.

The above ending confirmed Pawel Pawlikowski’s 2004 British drama “My Summer of Love” as my (belated) Valentine’s Day recommendation. The protagonists spend a summer together in the Yorkshire countryside. In a swift twirl from meet-cute to wine-drunk dancing and furtive making out, Tamsin (Emily Blunt) and Mona (Natalie Press) play out strong mutual infatuation. Due to the film’s languorous, drippy fairytale quality and utter lack of externality, viewers have the option to enjoy it as simply a dark and funny teen romance. But there is a lot in the movie to chat about — its comments on enchantment and religion, the slippery handheld cinematography, the sapid soundscape and the dark humor. This Valentine season, I want to discuss how the film addresses class inequality in romantic relationships.

I was taken by the interesting stealth with which Pawlikowski delivers the class subtext in this movie. In contrast, other depictions of class disparity in romance (I’m thinking “The Great Gatsby,” “Lady & the Tramp,” “My Fair Lady,” “Little Women,” etc.) suggest that to be infatuated with someone from a different social class (romantically or platonically) is dramatic enough to propel an entire plotline. “My Summer of Love” may be pretty confrontational about how different Mona’s and Tamsin’s lives are, but it veers away from using class as its driving plot.

There is a set of ways in which class status typically emerges as a plot device. One frequent depiction is of the dire propulsion to escape one’s place in society. In “Great Expectations,” Pip informs Biddy he wants to be a gentleman. Christine from “Lady Bird” scrambles to escape her life in Sacramento by applying to east-coast colleges. A second frequent depiction is a strong contempt for the upper classes. Elizabeth Bennet (“Pride and Prejudice”), Jenny Cavilleri (“Love Story”) and Jack (“Titanic”) are unimpressed by the wealthy. Often there is a Dostoyevskian curdling of rancor and covetousness, as in the case of Dan Humphrey from “Gossip Girl” and Lily from “The House of Mirth.” A third theme is the nausea of shame. When Christine from “Lady Bird” befriends her wealthier classmates, she lies to them about where she lives. In the children’s novel “When You Reach Me,” the protagonist is mortified by her apartment upon having a wealthier friend over.

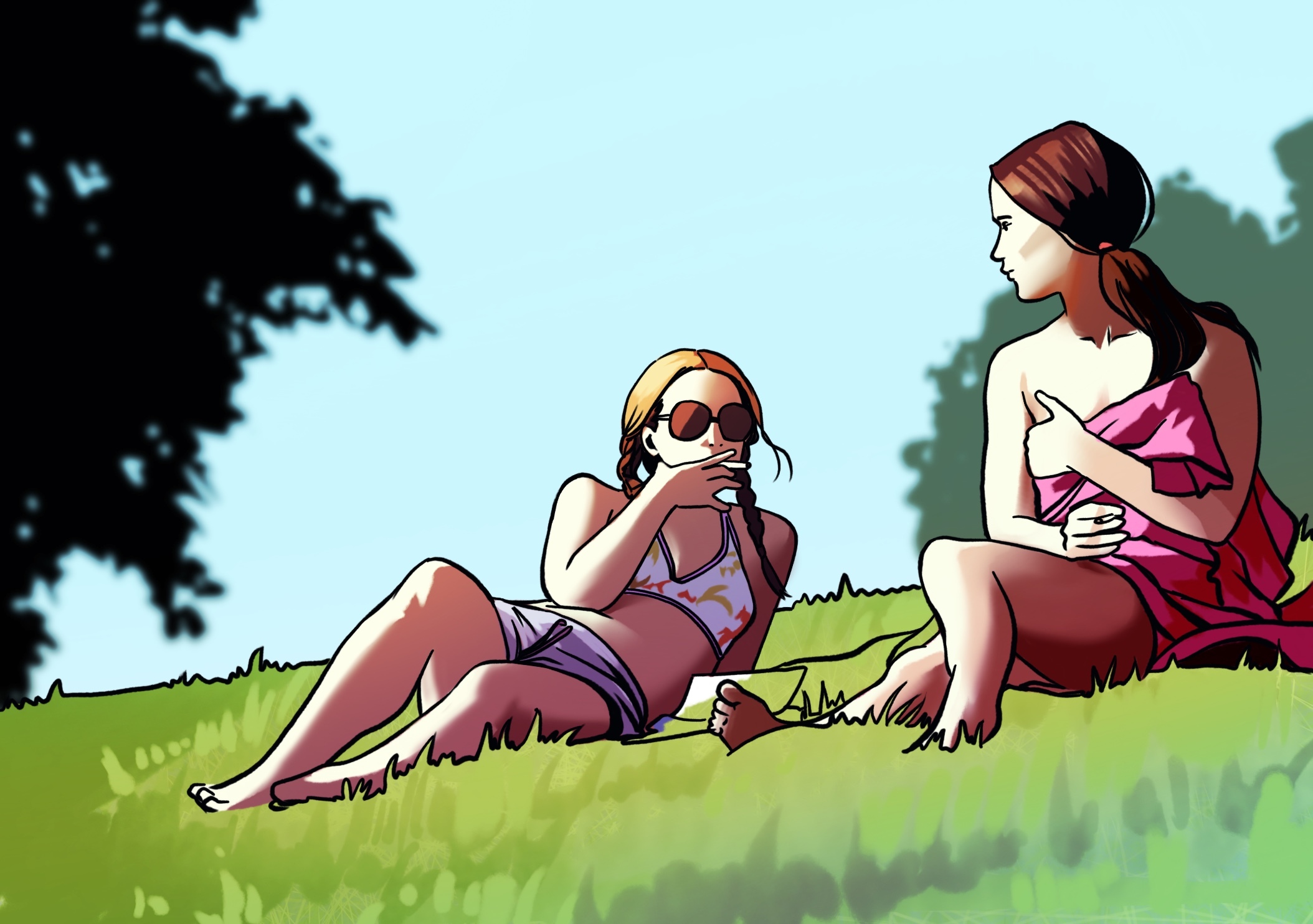

Visually, “My Summer of Love” is a comment on class with cartoonish veracity, but there is no such explicit treatment of class anxiety. There are no instances of the wet mouthful feelings of shame, inferiority or resentment that usually lace these depictions — something which is evident right from the opening segment. Mona rides her engineless Honda, juddering down a dusty path. As she lays sunbathing in a meadow, her eyes flicker open to the clomping of hooves and the purring snorts of a horse. The camera cuts from Mona’s eye to the horse’s, which is towering above her and is shot from below, as though the horse and its wealthy rider have magically materialized. “I’m Tamsin,” announces the beautiful, posh girl riding the white steed. Mona’s feet dangle as her engineless motorbike clatters and wobbles down the slope, while Tamsin’s horse, tall and powerful, trots along fully under her control. This foreshadows the authority Tamsin will assert throughout the movie, and Mona’s increasing lack of control over her surroundings — but neither ever minds. They are content, even thrilled, to simply be around each other.

The movie upturns this sweetness right at the very end. In one sweep, the film makes an interesting and despondent observation about cross-class infatuation: the grandiose, escapist vocabulary of romance means entirely different things to people from different classes. “We must never be parted,” Mona warns Tamsin after a night of shrooms. “If you leave me I’ll kill you.” Mona is in earnest rapture of these promises, but the same fails to be true for Tamsin.

After being physically abused by her older brother, Mona packs her stuff up, fully intent on running away with Tamsin. When she shows up at Tamsin’s ivy-draped mansion, however, Tamsin is cold. Tamsin says she’s returning to boarding school. Even worse, the sister she claimed had died of anorexia appears fully healthy and alive, and demands her top back from Mona. Tamsin’s seemingly earnest confession of her past trauma was all a lie: Mona bursts into tears and flees.

Tamsin follows Mona into the forest. “Sadie [referring to her supposedly dead sister] was just a bit of poetic license. I mean, I’m a fantasist. You can’t tell me we haven’t had fun,” she says. For the first time, the innocence of Mona’s infatuation thins and snaps and is replaced by the ugly realization that their romantic promises meant entirely different things to the two girls. For Mona, who lives in a pub with her violent ex-convict brother, who has no parents and no financial security, the need for escape is existential. For Tamsin, who lives in a Georgian stone manor in a massive enclosure, plays the cello and solemnly proffers recommendations of Freud and Nietzsche, “escape” is just summer romance. Just play. Just fun. For all of the movie’s glowing and candied colors, the aftertaste is decidedly ugly. Tamsin’s disrespect shudders through us like the realization of a paper cut.

What was Pawlikowski’s point with this eager, oblivious narrative and romantic momentum? Why was class conflict never the issue driving the plot? Why were our expectations only upturned at the very end? We can find some answers by comparing “My Summer of Love” to Ottessa Moshfegh’s novel “Eileen,” which points out that the realities of asymmetry are often realized only in retrospect. In “Eileen,” Ottessa Moshfegh retrospectively narrates a similar tale of one woman’s infatuation with another. Since it is narrated in the distant future from when the events took place, the narrator, Eileen, is explicitly able to psychoanalyze herself to realize that her rapture with Rebecca was driven by their class differences. Meanwhile, Pawlikowski is capturing the real-time experience of infatuation, a stage at which the opportunity to parse apart the buried power games and the influence of class has not arisen — which is why the movie’s regulation of the viewer’s psyche and investment is so brilliant: we are immersed in the infatuation; we feel the sharp slam of our chins against the ground when the fantasy finally keels over.

In the end, “My Summer of Love” is straightforward in its prettiness. I am grateful for the many days Pawlikowski spent location-scouting, hiking the Yorkshire hills with a camera. The long shots of the cross on the hill made their point — that infatuation is a glorious, thick-skinned dream.