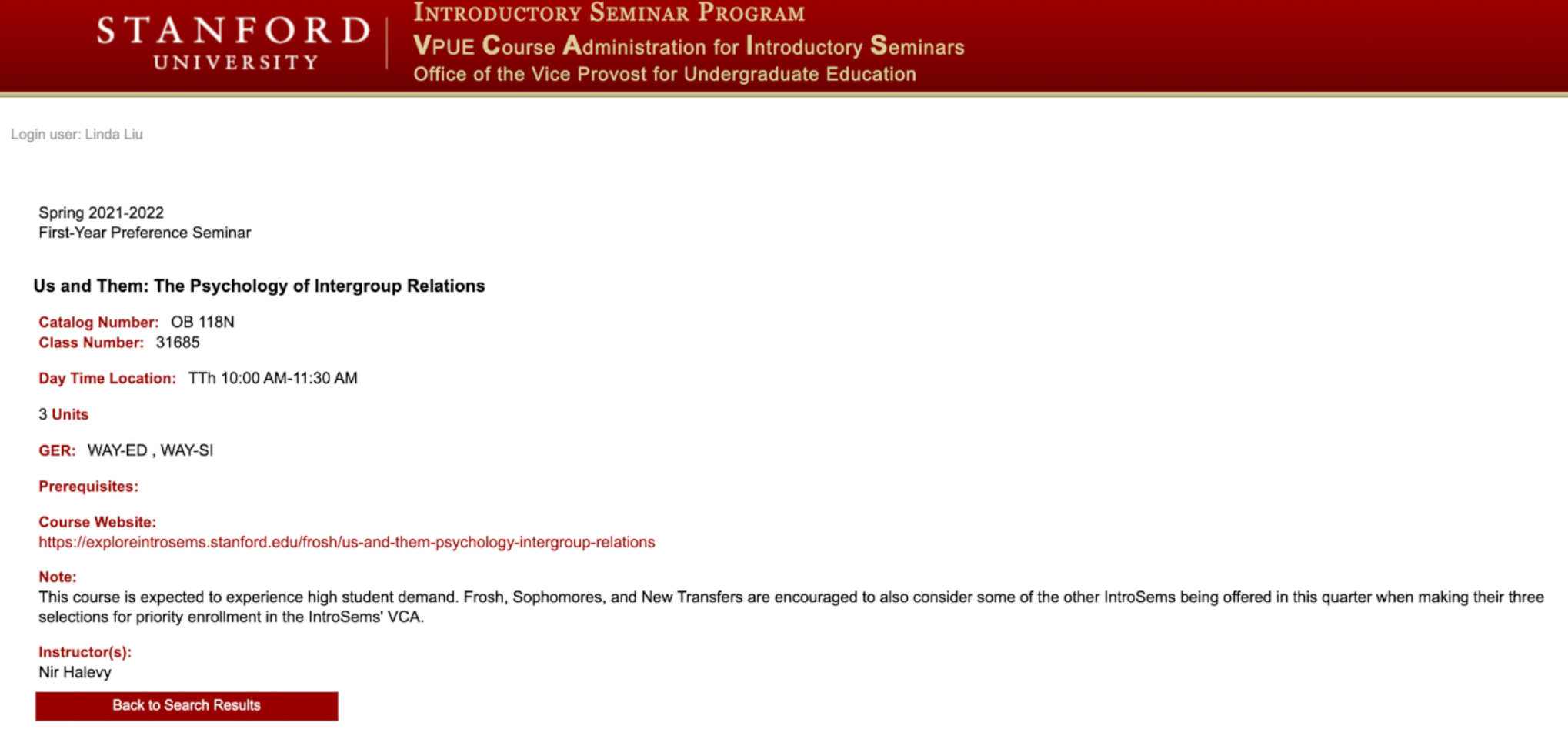

Browsing through the list of Introductory Seminars offered for Spring Quarter, clicking on one only to find that “This course is expected to experience high student demand,” hunting down memory lane for details to declare love for a particular subject … such is the rite of passage of frosh and sophomores — gambling in the IntroSem game.

Legend has it that Stanford IntroSems are modeled after MIT Undergraduate Seminars, electives offering hands-on learning for subjects such as astronomy and nuclear fusion and graded with a simple pass/fail. Providing small-group settings for students to engage in seminar-style discussions with professors that are leading experts in their fields, IntroSems are some of the most sought-after courses at Stanford, whether for their moderate workload, easy fulfillment of General Education Requirements or niche subject matter. Every year, frosh and sophomores make their bids on their top three choices, ordering them strategically and pouring their hearts out on the application, praying that one or two of their ideas catch the professors’ eyes. “This is the college application process all over again,” remarked those around me.

Stanford advertises IntroSems as being “equally valuable both as a place to experiment with something entirely new and to build on existing knowledge.” However, this principle of accessibility often contradicts the competitive nature of some offerings that receive as many as 300 applications. To be able to stand out as the lucky “winner” often requires us to have prior knowledge on the subject and be able to write a nuanced application essay. Unable to come up with a better explanation of my interest other than “I am fascinated by the scientifically accurate details of Interstellar planets,” I crossed “Designing Science Fiction Planets” off of my “considering” list despite its promise to fulfill the Ways – Scientific Method and Analysis requirement for a humanities major.

The way that the current IntroSem application process favors those with prior experience in the subject conflicts with the curriculum of the courses, which are “designed to be accessible to first-year students regardless of prior high-school background.” Therefore, walking into class expecting for their previous conception of Regency-era literature to be revolutionized by in-depth discussions, prospective English majors in “Jane Austen’s Fiction” might find themselves rereading the same novels and engaging in conversations that do not go beyond a plot summary and historical context. Students often face the choice of selecting between a seminar on a subject matter they are curious about versus one aligned with their previous studies, which may be easier to get in yet limits their scope of exploration.

Granted, students often make fascinating new discoveries when delving into a previously studied topic under the guidance of knowledgeable professors and when hearing new perspectives from diverse peers. Taking “Theatrical Wonders from Shakespeare to Mozart” last quarter, I greatly enjoyed analyzing film and ballet adaptations of the Shakespearean plays I had previously read. I was also grateful to have gotten to know a leading Renaissance scholar, Professor Blair Hoxby, whose research interests aligned with my then-intended English major.

Regardless, the IntroSem application system and course curriculum inadequately address the needs of both those seeking to take a first dive and those desiring more intellectual challenge in a particular subject. To do so, Stanford should consider separating seminar offerings into those that cater to beginners and those designed for students with previous exposure to the field. The latter would be able to move beyond discussions about basic information yet still remain distinct from advanced seminars in their relatively low demand on analytical skills. Professors should note their preferences for the knowledge background of their students on their course pages instead of simply using the official blanket statement, “[IntroSems] rarely have prerequisites, except curiosity and an open mind.” With their courses more narrowly tailored to specific student needs, professors will have more direction when selecting desired students for their seminars, which in turn will contribute to admitted students having a more equal voice in class discussions.

Additionally, Stanford should create more opportunities for students to participate in the more competitive IntroSems. The existing label of high-demand courses helps students set expectations for their chances of admission but often bars those with limited experience and less to present in their essays from applying. Opening multiple sessions for offerings such as “Things About Stuff” throughout the year could introduce the field of electrical engineering to more students through accessible discussions about its application in life around them. To achieve this may mean recruiting more professors to teach the same seminar, each having their own different specializations and teaching styles.

While the current IntroSem system still offers rich opportunities, such as lively discussions and valuable friendships, it will remain far from achieving its full potential until Stanford reforms the system to cater to students’ specific needs.