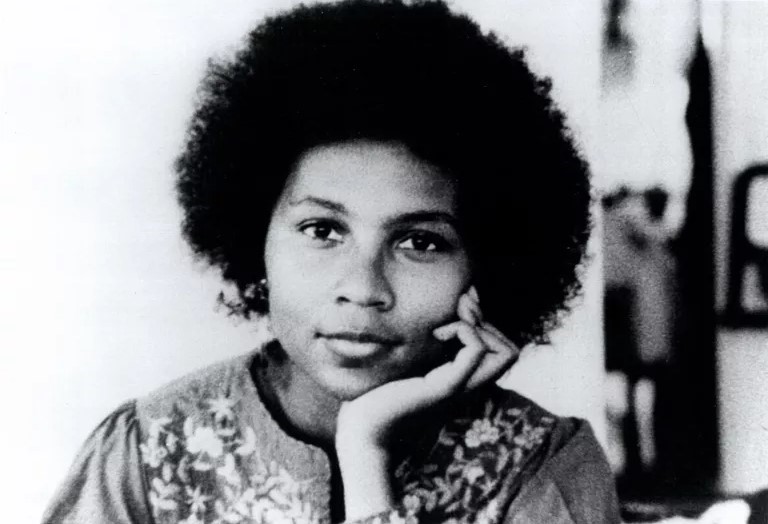

bell hooks ’73, author, professor, activist and queer Black feminist scholar, died on Dec. 15 at the age of 69. Her written works played a significant role in expanding notions of feminism to include Black and working-class women.

Born Gloria Jean Watkins in Hopkinsville, Ky., hooks chose her pen name as a tribute to her great-grandmother Bell Blair Hooks, insisting that her name be spelled without capital letters to deemphasize her individual identity. By doing so, hooks hoped to focus the public on the substance of her work and ideas, rather than race and socioeconomic status that made her and others susceptible to marginalization.

hooks identified as “queer-pas-gay,” writing that she defined queerness as “the self that is at odds with everything around it and has to invent and create and find a place to speak and to thrive and to live.”

Remembered for works such as “Ain’t I a Woman?: Black Women and Feminism” and “All About Love: New Visions,” hooks dedicated much of her writing to dissecting her community’s norms and fighting the oppressive structures that held it — and similarly marginalized communities — back.

Her writing was known within and outside of academia but was especially valued within the Black community. Many young Black scholars, particularly those at historically Black colleges and universities, read and analyze hooks’ work.

Katie Dieter, associate director of the African and African American Studies Program (AAAS) at Stanford, first encountered hooks as a freshman in college, when she read “Ain’t I a Woman” and “Teaching to Transgress.”

“They truly saved my life,” Dieter said in an email. “I became consumed with all of [hooks’] work — The way she told stories, how she connected theory to her life and the lives of others — I had never read work like hers before.”

Throughout her career, hooks strove to provoke deep thought among her community and make change from within, doing so by creating a platform to discuss love as both an action and an emotion.

Dieter credits hooks’ words with inspiring her to pursue a career in Black studies.

“She gave me the courage to bring my whole self into my work and my life — the parts of myself that I used to be ashamed of were now front and center and fueled my passion to better serve the communities that mean so much to me,” Dieter said.

hooks rose to prominence in the 1970s as a professor of English and ethnic studies at the University of Southern California. Throughout the seventies and the decades that followed, hooks published her most acclaimed works of theory and cultural criticism, including “Feminist Theory: from Margin to Center.”

“[hooks] emerged intellectually and creatively at a time of efflorescence in Black women’s theory and literature,” said AAAS Interim Director and associate English professor Vaughn Rasberry. “I think that is part of the ultimate meaning of her place in departments of African and African American Studies in the United States, and abroad, as well.”

Rasberry emphasized the tremendous impact that hooks has had on Black academia: “In the establishment of Black feminist theory and critique in universities, and particularly in departments of African American students, it’s hard to imagine it’s prominence today, if it weren’t for hooks.”

hooks’ impact on college students is no accident — she possessed a unique sense of curiosity about how young people think and frequently embarked on lecture tours at universities around the country. She returned to Stanford several times after her graduation to teach and lecture, but coming back to the campus where she wrote her first draft of “Ain’t I a Woman” was a harsh reminder of the privilege and classism she observed as an undergraduate.

In “Where We Stand: Class Matters,” hooks writes that “at the university where the founder, Leland Stanford, had imagined different classes meeting on common ground, I learned how deeply individuals with class privilege feared and hated the working classes. Hearing classmates express contempt and hatred toward people who did not come from the right backgrounds shocked me.”

hooks will undoubtedly be remembered as a fearless cultural critic and leader in the field of Black feminism. While she maintained her passion for the study of race and gender over the course of her career, hooks’ later work focused increasingly on the power of love.

“I want my work to be about healing,” hooks said at her induction into the Kentucky Writers’ Hall of Fame in 2018. “I am a fortunate writer because every day of my life, practically, I get a letter, a phone call from someone who tells me how my work has transformed their life.”

Through her focus on love, hooks was able to find a universal truth shared among groups when it seemed like they couldn’t have been more different.

“Occasionally we find major thinkers who meditate on the meaning of love, but hooks did so in a sustained and powerful and imaginative way for a long time,” Rasberry said.

A fearless scholar who dove headfirst into spaces where she and others like her have traditionally been marginalized, hooks was never one to shy away from a challenge. If she was ever fazed while at Stanford, hooks did not show it, instead channeling her energy into scholarship and activism —the work she produced as an undergraduate and beyond forming a basis for students throughout the world to draw on.

Dieter reflected on the influence hooks’ work will have for years to come: “Her work on topics such as Black feminism, intersectionality, critical thinking, the media, and love taught us how to critique and resist systems of domination in ways that truly transform our lives and our communities.”

This article has been updated to include information about hooks’ queer identity.