The first event of HOWLoween Wolf Awareness Week, “The Beats Within: Comparing AI & Human Adaptations of ’Howl,’” took place on Zoom this Monday. Organized by Stanford Libraries, the presentation explored different interpretations of Allen Ginsberg’s iconic poem “Howl” by both foreign language translators and artificial intelligence (AI) systems.

“It’s an incredibly difficult poem to translate. It makes use of references, colloquialism, vernacular and different illusions. It’s an immensely challenging poem,” said Stanford Libraries Curator of Germanic Collections and Medieval Studies Kathleen Smith.

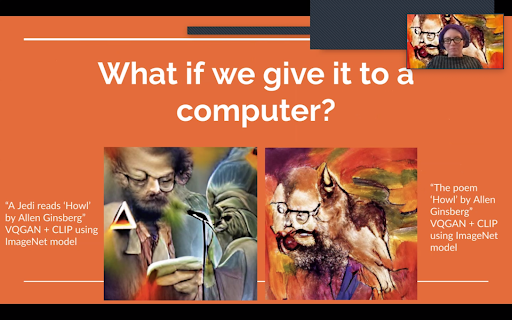

The difficulty of interpreting this poem is perhaps best displayed in how AI systems process the poem. Academic technology specialist Quinn Dombrowski showed attendees an ambiguous amalgamation of colors and creatures, and explained that it was an effort by AI to decipher the poem. It is a translation of the poem by a non-human entity that presents a completely different perspective on the work.

Similarly to how AI puts the poem in a new light, spoken language differences also uniquely frame the work. Even the translation of the poem’s title differs depending on language; in some, howl is translated as a verb, and in others, as a noun, the event speakers said. The German translation is “The Howl,” which Smith said “has a distancing effect and raises questions about how we interpret the original language of the poem.” In addition, the Hebrew translation adds a biblical aspect to the poem that cannot be found in the English version.

Smith also mentioned how the cultural context and identity of a translator can affect the translation. For example, readers interpret the first ever translation of the poem by Fernando Alegría with underlying political meaning, because Alegría was an activist and the leading voice of the Chilean community in exile in the US.

Other examples of culturally-informed translations are Fernanda Pivano’s Italian translation, which created a sentiment of anti-fascist resistance, and the Polish translation, in which the word queer was translated as “odd,” rather than “gay,” to reclaim an insulting term and create a poem of LGBTQ+ pride, Smith said. Smith added that translations are not static — even translations of the poem in the same language can shift in meaning throughout time.

The myriad of different interpretations of “Howl” generated through language translation were what inspired Dombrowski to explore computer analysis of the text.

“It takes all the knowledge that it has of English text and then fine-tunes the probabilities of different words based on the text that you retrain it on,” Dombrowski said, explaining the software analysis process. Programs like GPT-2, VQGAN and CLIP were used to analyze the poem.

Trained using texts of other poets or television shows, AI generated its own translation and illustration of “Howl.” Some AI translations retained the poetic nature of the text, some added comical elements and one even produced a lyrical speech spoken by Jabba the Hutt.

But not all of the AI interpretations were engaging — some were repetitive or nonsensical. Others reflected human bias and discrimination. These versions occurred because the training data had human “biases baked into the algorithms,” Dombrowski said.

These biased iterations showed that although we live in a society that is becoming increasingly reliant on AI, it is important to remember that our systems can be faulty. The computer does not actually know anything other than what it has been fed.

“While AI can be hilarious to laugh at, it’s worth being wary and thoughtful before adopting it in any way as a substitute for human judgement or even as a supplement to it,” Dombrowski said.

Even then, it is fascinating to see the many afterlives of one iconic poem, now even being produced by technology that allows for interpretation beyond human capabilities. The intricacies of Ginsberg’s poem allow both human and non-human readers to translate it uniquely and yield a sense of immortality to the work.