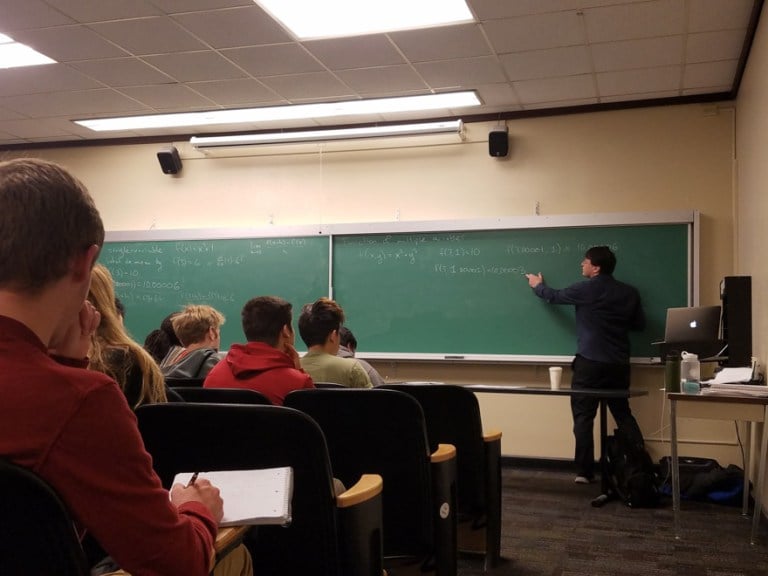

When mathematics lecturer Christine Taylor asked her Math 51 students in class whether they prefer she write on chalkboards or project her lecture notes, the students were in lockstep: chalkboards are better. And the students are not alone in their preference.

Mathematics professor Brian Conrad, the director of undergraduate studies for the Mathematics Department, said that nearly 100% of math faculty members at Stanford teach using chalk and chalkboards. This partiality for chalk, according to fourth-year Mathematics Ph.D. student Libby Taylor, is shared by graduate students and teaching assistants.

Since the invention of colored chalk and chalkboards in the early 1800s, the instruments have been widely used in educational settings. In fact, many mathematicians today have even developed brand loyalty for a specific type of chalk — Japanese Hagoromo chalk, which is the brand preferred by many math faculty at Stanford.

When Conrad heard about the bankruptcy of the Japanese company which produced Hagoromo chalk a few years ago, he described the situation as a “chalk apocalypse” and started stockpiling chalk as much as he could. The news that a Korean company bought the Hagoromo formula relaxed the sense of urgency but did not diminish mathematicians’ fervor for the chalk. Libby Taylor even said that there was hardly any non-Hagoromo chalk in her office.

While the use of chalk is a cultural element for most mathematicians, Conrad also noted several distinct features of chalk in comparison with slides or projections. The nature of mathematical derivations and the step-by-step process is hard to capture through slides, he said.

Although using slides is more useful when giving a “popular audience talk,” chalk and chalkboards are much more effective for classroom instruction, Conrad said.

Echoing Conrad’s sentiment, Christine Taylor said that “if the speaker tried to use slides, people don’t retain as much because [the speaker] goes much faster. Whereas if you write on the chalk, you are forced to slow down.”

The more spacious chalkboard versus the limited screen size, Conrad said, is conducive to students’ learning as they can constantly go back and forth on mathematical derivations. The layout in Room 380C of Sloan Hall, for instance, has two levels of chalkboards, which allow for enhanced flexibility.

Even when compared to whiteboards, chalkboards still have many benefits. One always knows how much they have left with a piece of chalk, according to Conrad. With whiteboard markers, however, one never knows when the markers are going to run out — a phenomenon jocularly described by Libby Taylor as “whiteboard marker roulette.”

With regard to teaching, Christine Taylor noted that an individual’s “penmanship is not as good with markers,” and that when circling with markers, “the writing tends to get smaller,” which tends to make it more difficult for students to discern. On a more practical level, Libby Taylor said that “whiteboards do deteriorate much faster, [and] then you have to replace them much more often and mounting these boards is an enormous pain.”

Chalkboards, on the other hand, can still work perfectly even when they are 20 or 30 years old. Conrad also pointed out that if one accidentally applies permanent markers on a whiteboard, then the board would be “instantly dead,” a nightmare not applicable to chalkboards.

Even though assistant mathematics professor Zhenkun Li has no particular preference for chalkboards or whiteboards for personal use, when meeting with a student or colleague, he still prefers the chalkboard.

Using chalk and chalkboards is not only conducive to teaching and learning, but it also has environmental benefits. Conrad said that “chalk is more biodegradable” and that chalkboards, unlike whiteboards, do not require chemicals when cleaning.

Despite the many benefits chalk and chalkboards have, they are slowly disappearing. Conrad mentioned that “many, many, many high schools have completely gotten rid of” chalkboards.

Chalkboards were long gone at Palo Alto High School when he went to speak there, he said. In one of his Math 51 classes in 2018, he added, “almost none” of the students “had been in a chalk lecture before coming to Stanford.”

Li remarked that with this phenomenon, when coupled with the recent pandemic which led to the prevalence of online seminars, it’s possible that technology will be used more often in math classrooms. However, others interviewed by The Daily all seem to think that chalk and chalkboards will remain a fixture in mathematics education for years to come.

Whether it be because of “the tradition of using chalk,” as Conrad noted or the “nice clickety clack noise” that Libby Taylor mentioned, chalk and chalkboards are here to stay.