Experiential disparities in the criminal justice system are prevalent in court outcomes and in differences in the quality of an individual’s court experience, said sociology assistant professor Matthew Clair during a Wednesday afternoon event.

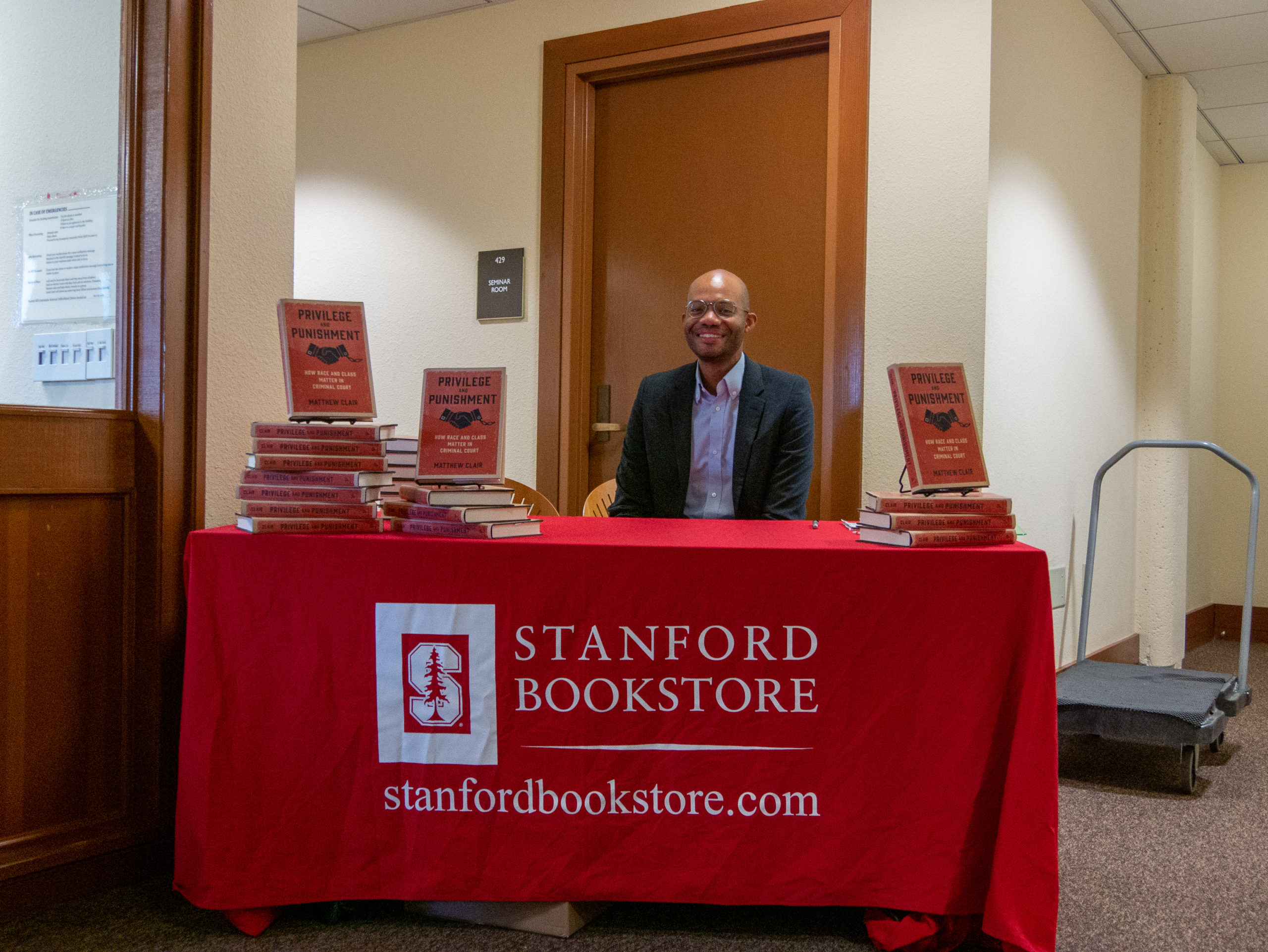

Clair spoke about his research for his new book, “Privilege and Punishment: How Race and Class Matter in Criminal Court,” during the first in-person faculty talk hosted by the American Studies program in two years.

Clair’s book focuses on 63 case studies that he conducted during field work in the Boston court system and examines interactions between defendants and attorneys both inside and outside of the courtroom. Clair urged the readers and audience members to focus on the micro-level of the criminal justice system to understand the macro-level — starting with the defendant-attorney relationship.

As Clair recounted his time with defendants and attorneys during his field work, he reflected on his discovery of a lack of trust, disagreement in legal choices and an overall misunderstanding of what justice means in the grand scheme of their cases between the two parties.

“For the people in this study, mistrust arose from a set of conditions rooted in poverty and racism — in particular, the perceived and real structure of the indigent system produced high levels of mistrust,” Clair said.

Individual opinion of the courts is also cultivated through past experiences and generational community memory, according to Clair. During his research, he noticed that the self-advocacy by lower-class clients and defendants of color often led to harmful outcomes because it put them at odds with their attorney, thus breaking their trust and desire to work with them. Contrastingly, the privileged defendants delegated their work to their lawyers and were overall ignorant of court proceedings. In his book, he asserted that “privileged people were rewarded for their deference, whereas the disadvantaged were punished for their resistance and demands for justice.”

Clair also stressed that, too often, disadvantaged defendants are silenced and coerced during their time in the legal system, ultimately leading to their withdrawal from the process altogether. And too often, the attorneys are blind to this. He echoed this phenomenon in his book, writing: “It is ironic that a social institution ostensibly meant to ensure justice in our society seeks instead to avoid accounting for the injustices that bring people in contact with it and that influence the way people are able to navigate its walls.”

Event attendee Katie Eder ‘24 said that she appreciated Clair’s examination of courtroom relationships in his talk, especially because she had never considered how these relationships fit into the broader criminal legal system.

“Professor Clair has honed in on this very specific component of the criminal legal system and the injustices around it, which is the relationship between the defendant and attorney,” she said.

Some attendees, such as American Studies program director Shelley Fishkin, felt renewed after Clair’s event. Fishkin said that the event sparked within her an urge to “make the system of justice more equitable and also perhaps less oppressive in the ways that he showed it to be.”

Clair concluded his talk with a warning to not underscore the severity of the issue at hand when reading his book and to consider the implications of his findings for other cities.

“The problems I uncovered in Boston, which actually has a very well resourced indigent defense system compared to others in the United States, are likely more extreme than other jurisdictions — because of that precisely.”