In one of the stories from her new short story collection “In the Event of Contact,” Ethel Rohan’s narrator quotes Oscar Wilde: “Each man kills the thing he loves.” After reflecting more on the quote, she then gives a slightly different version: “It seemed far more true that we kill parts inside those we should love the most, ourselves included.”

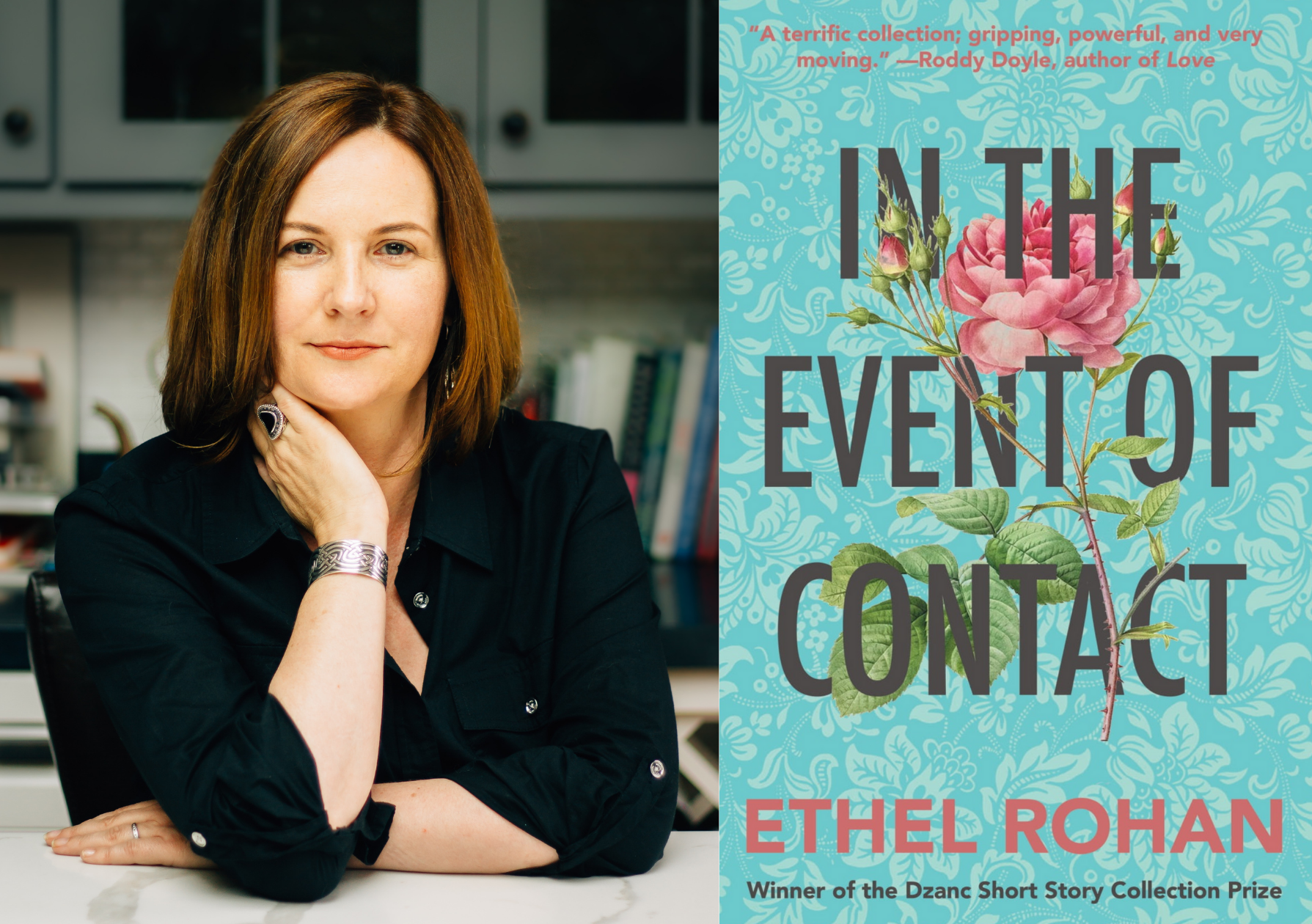

“In the Event of Contact,” winner of the Dzanc Short Story Collection Prize and out Tuesday from Dzanc Books, could perhaps be read in the light of this revision. The 14 stories in Rohan’s collection are wide-ranging, but what they all share is an eye trained toward the complications of the interpersonal. Her characters — unified by their Irish identities but spread out all over the world — navigate the pains and joys, the difficulties and beauties, that come with the universal desire to love and be loved.

The love explored in this collection is not confined to the romantic; familial, platonic and self-love are just as important to Rohan as she builds this chronicle of human connection. From two old women who meet an American cyclist in a bar to a man who takes his mother horseback riding, from an aspiring pilot to an aspiring detective, these stories, while relatively short, craft convincing characters in situations of personal and interpersonal conflict.

“In the Event of Contact” also suggests that equally essential to understanding how much we need connection with other people is the absence of connection. In the story “Everywhere She Went,” the first-person narrator is haunted by the absence of her childhood friend Hazel, who was kidnapped and disappeared when they were both 10 years old. From the opening paragraph of the story, we are attuned to the narrator’s profound sense of loss; at the bar, she notices, “Everywhere, drinks in various stages of disappearing.”

As the story continues, the narrator’s fixation on her absent friend eclipses her relationship with her boyfriend, as if Hazel is not just a memory but a real, tangible presence in the narrator’s present life. Rohan writes, “To this day, her sky eyes hang over everything.”

Finally, “In the Event of Contact” is not only about reciprocal relationships like those between family members, significant others or friends: It is also about the lasting trauma and violence one person can inflict on another, particularly the predatory violence men can inflict on girls and women. In “Everywhere She Went,” the trauma of Hazel’s disappearance lives on in the narrator years after the event. While she is teaching in her classroom, the narrator’s “tender gaze runs over the rows of pubescent schoolgirls, every one a bull’s-eye in this sick world.”

This rings true in the titular and first story of the collection, where we have a young narrator who is a triplet. One of her sisters, Ruth, has a serious aversion to physical touch — any contact with another person causes her to have a seizure. As a result, attending school becomes difficult, and so the family hires a private tutor named Mr. Doherty.

The narrator doesn’t like Mr. Doherty, despite the fact that he is sympathetic to Ruth’s condition. And, indeed, it seems that he is too sympathetic to it, remarking to the narrator, “Poor Ruth … To be beyond touch. It’s almost impossible to imagine. She’s like the sun.” Later, she spies on the two of them playing together in the garden. Mr. Doherty sprinkles dirt and flowers on Ruth’s bare midriff.

With this story, Rohan combines two powerfully different but connected perspectives on human contact. On the one hand, the narrator expresses her jealousy of Mr. Doherty; she wishes she could be the one so close to Ruth, her own sister. “A sharp ache filled my chest,” she says. “Why hadn’t I ever thought to do this for Ruth?”

But we know there is something else behind this ache, this unease. The narrator’s disgust perhaps comes from an innate understanding that the older man is exploiting Ruth’s trust to get closer to her. The innocence of the young girl is prematurely marred: “Mary and I, we would have made it beautiful. With Mr. Doherty, it was obscene.”

Throughout “In the Event of Contact,” Rohan offers compassionate and vivid portraits of people looking for connection. Yet, in these searches, we see that we can find ourselves fragmented, sidetracked and in places we never expected. Such is the route by which we come to discover “that thing called love.”

In an earlier version of this article the publication date for this book was inaccurately stated as “tomorrow” rather than Tuesday. The Daily regrets this error.