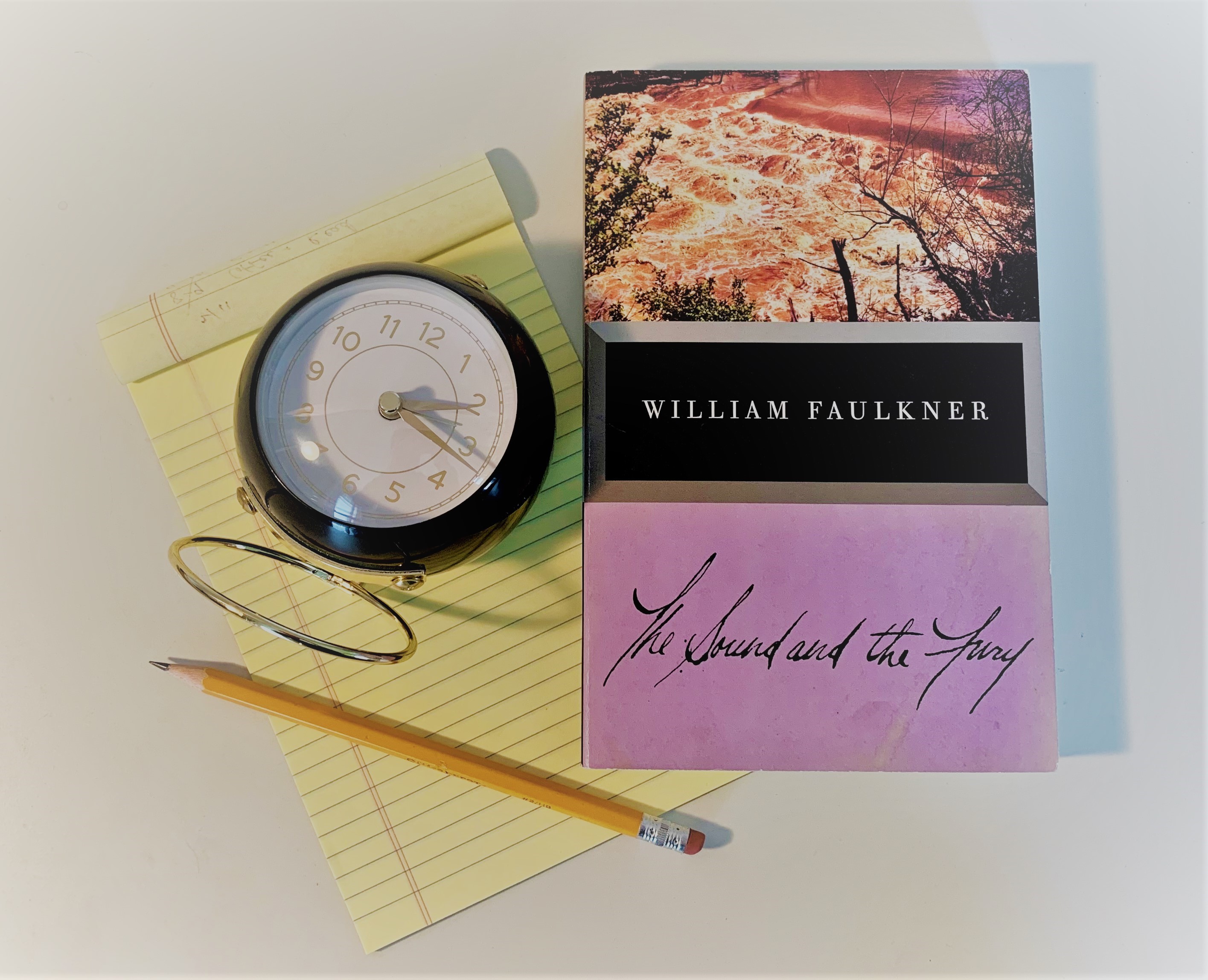

This marks the first article in a new Reads column “Classics for quarantine.” Each week, I will reflect on a literary classic’s contemporary relevances and resonances in the context of COVID-19 and the experience of living in quarantine. Some connections may be obvious, others less so. Ultimately, my goal is to articulate how reading old literature — the stuffy stuff of syllabi — has helped me make some sense of my present.

The clock is my companion. Maybe even more than I’d like to admit. It has been a year of staring at my computer for hours on end, checking the time in the bottom corner of my taskbar or on the lock screen of my phone. This motion is almost second nature. Sometimes I have to pick up the phone twice: once to check the clock, twice to really check it, having immediately forgotten the time upon glazing over the digits. Somehow, this digital rendition of Father Time has always made me feel like the minutes are imperceptibly slipping away from me, a silent change of the numbers. Numbers, numbers — and that convenient little colon in the middle, which seems to make it too easy, as if the experience of time is a simple and logical mathematical equation. Counting life away.

But if this year has taught me anything, it is that time is fickle, more fickle than perhaps I ever thought before. What do seconds, minutes and hours mean when whole months are spent inside? We cannot rely on those effortless numbers anymore. Have I really spent a whole year in the same room? Was it really so long ago that I last saw my friends, went to a class in person, wrote a paper at the library? Time becomes spatial: Each moment no longer passes to the next, but instead stays, circulates heavily in the air, stuck like food that will not digest. Memory is simultaneously vivid and vague, everything at once and nothing at all. A universe and a vacuum.

***

William Faulkner’s “The Sound and the Fury” tells the story of the Compsons, a family of Southern aristocrats who have lost their former wealth and prestige. Though the narration of the novel only takes place over the course of four days (three consecutive, one many years earlier), we see the way the family falls apart through the early decades of the 20th century. In this way, time is the Compsons’ undoing.

Of the four Compson children, Quentin — intelligent, proud, cynical Quentin — is the most haunted by time. His chapter, “June 2, 1920,” takes place the day before his suicide, and consists of his movements through Cambridge mixed with his inner thoughts and the intrusions of his memory. Like me, Quentin’s companion is the clock. Theirs is almost something like an abusive relationship. Time dogs Quentin, pursues him wherever he goes. He hates it: At the beginning of the chapter, he breaks the watch his father gave him, shattering the glass and twisting the hands off its face. Yet he also seeks it out, constantly listening for the sound of time from the broken watch or the bell tower that chimes every quarter hour — the indication that time is, indeed, still moving: “The watch ticked on. I turned the face up, the blank dial with little wheels clicking and clicking behind it, not knowing any better.” The sound of time marks for Quentin that inevitable movement toward degradation, of his family and of himself.

A few weeks ago, I borrowed a cheap analog clock from my brother. I thought it might help reduce the amount of times I impulsively picked up my iPhone. He warned me that it was loud, that I wouldn’t be able to focus or sleep with it running. I’m not a light sleeper, so I ignored him, put in new batteries and sat it on my desk. But he was right: It ticked the hours away, loudly. I became hyper-aware of time. It was just as Quentin says — “You can be oblivious to the sound for a long time, then in a second of ticking it can create in the mind unbroken the long diminishing parade of time you didn’t hear.” As soon as I heard the second hand’s steady metronome, I could not block it out. It was all I thought about.

And then, alone in my room, listening to the clock for who knows how long, I began to feel the slow march to insanity, or death. I heard Quentin in my ear:

“Because Father said clocks slay time. He said time is dead as long as it is being clicked off by little wheels; only where the clock stops does time come to life.”

Perhaps I implicitly hoped for something more to come of my reversion to the analog. In the opening paragraph of his chapter, Quentin remembers his father’s words when he gave him the watch: “I give it to you not that you may remember time, but that you might forget it now and then for a moment and not spend all your breath trying to conquer it.”

But Quentin cannot forget time. Left alone with only time for company, it takes on that heavy quality in which you know it contains the dredges of the past. Memories from long ago revisit us again and again; the span of our life compresses into a consolidated space. Throughout his chapter, formative moments from Quentin’s past take on another vivid life in the present, influencing his thoughts and actions and ultimately leading to his death.

***

Quentin cannot forget time, but can I? It may be months, maybe longer, before we are released from the confines of our interior spaces — physical and mental both. We track the cruel crawl of days, and then suddenly weeks have vanished into thin air. We lie in bed at night fighting away bad memories and nightmares. The siege of time feels never-ending.

Then again — it always has been, and always will be. Time wears us away, whether we count it or not. We cannot escape from our pasts; our selves are built upon memory, for “all men are just accumulations.” Why resist it? Why fight — why wrench the hands off the dial if the motors will continue to tick until the end of eternity? We do not need to be at war with time, because time will always win.

Instead of smashing my clock, I took the battery out. I gave it back to my brother. That afternoon in the new silence, I sat reading at my desk as the day moved into night, watching “that quality of light as if time really had stopped for a while, with the sun hanging just under the horizon.”

Contact Lily Nilipour at arts ‘at’ stanforddaily.com.