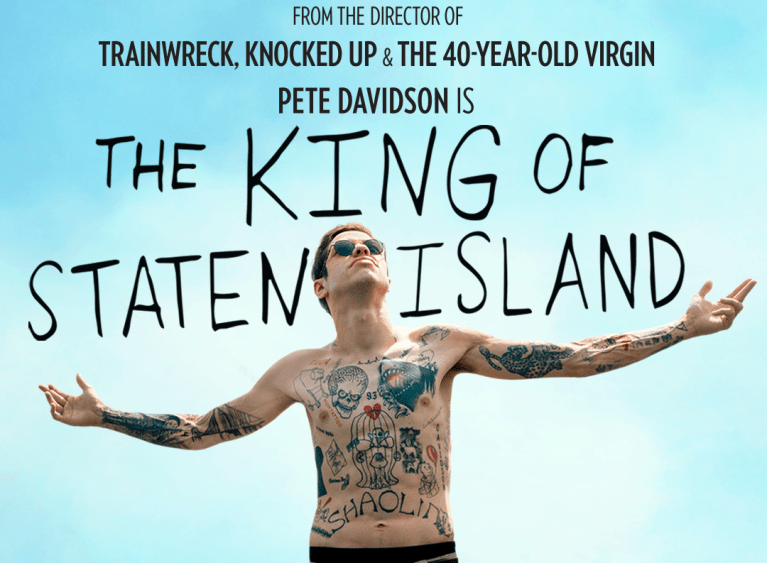

The line between Pete Davidson and his character Scott Carlin is pleasantly thin in Judd Apatow’s latest, “The King of Staten Island.” Davidson’s Scott is charming, bluff and boyish — neither a deviation from Apatow’s palate nor a fresh comedic archetype, but beloved nonetheless.

Co-written by Davidson, Apatow and Dave Sirus, the screenplay’s meandering nonchalance suits its emotionally stunted, stoner protagonist. Though the overbaked bildungsroman’s stylistic choices like this one are at times tiresome to the viewer — who is teased with short-lived moments of emotional rawness amid heaps of unproductive mumblecore — they culminate in a self-aware, decisive irreverence that is not lost on viewers. Despite its temporal and diegetic excess, “The King of Staten Island” ultimately delivers a tender treatise on grief and its bastard children.

Davidson has previously described the film as a reimagination of his life had he not discovered comedy. Essentially, we follow Davidson’s high school dropout alter ego Scott Carlin as he reckons with his arrested development post-losing his father Stan in a firefighting accident. While his younger sister Claire (Maude Apatow) is moving out for college and his mother Margie (Marisa Tomei) is working two jobs and revamping her love life, Scott spends most of his time getting high or getting laid, all the while loosely clinging to his pipe dream of opening a restaurant-tattoo parlor hybrid he calls “Ruby Tattoos-days.” Safe to say, he’s no hustler. But when Margie’s fireman boyfriend Ray — yes, even she admits she has a type — calls her out on coddling Scott, she pulls her safety net gradually out from underneath our leading man-child until he’s left essentially homeless. And then the movie really gets rolling (about one hour in).

The film’s most striking moments generally center around Scott’s latent anger towards his father and what seems to be a resultantly fraught relationship with his mental health. Apatow opens with a sequence wherein Scott narrowly avoids a car wreck while blaring King Chip’s “Just What I Am.” The few seconds the scene lasts are packed with sensory input and boil to an intensity typically delayed in comedies. Though borderline personality disorder (BPD) is never mentioned explicitly throughout the movie, this scene and subsequent ones unravel like explosive episodes characteristic of BPD, a diagnosis Davidson recently shared he received in 2017. Davidson disclosed in an interview with Variety that before his diagnosis, he “was always just so confused all the time, and just thought something was wrong, and didn’t know how to deal with it.” Davidson’s opening scene embodies this confusion to grip the viewer and garner their pathos from the get-go.

Disappointingly though, later brushes with mental illness do not reach the depth we were primed to anticipate. In one promising conversation with his childhood friend turned friend with benefits Kelsey (a show-stealing Bel Powley), Scott briefly lapses into a heart-wrenching confession about his fear of himself. Even so, there is no moment of rapture, and we soon see the teenage boy who is afraid of emotion tap back in for the child who is afraid of the dark. Most acknowledgments of Scott’s mental disorder are similarly transient — though at times, the brevity of these moments is their magic. For instance, when Scott admits to Kelsey mere seconds after her finishing that he can’t come because of his antidepressants, we are caught in that guilty laughter that is tinged with a bit of sadness. And it is perfect.

Aside from rounding out Scott’s character with these poignant scenes, the film also humanizes him deeply through his role as an older brother, both literally to Claire and metaphorically to Ray’s elementary-aged kids. Early in the story, Claire and Scott get into an argument because Claire insists Scott must come to her graduation party for appearance’s sake, even though she doesn’t actually want him there. Margie, who is making breakfast, makes an off-hand comment about how Scott will miss Claire once she is gone. In their garage the next morning, Scott pieces through Stan’s photos and uniform, then gives a touching rehearsal speech to no one, topping it off with a brilliant callback, “I’m gonna really miss you.” Though Claire never hears him admit his affection toward her, we keep it in mind each time he takes a future jab at her, and even at others. It is this undercurrent of sympathy that leads us to permit Scott’s indiscretions and continue rooting for him. The film gently tugs us to look at Scott’s emotional distance as a coping mechanism that is disagreeable to his character but inevitable as a fallen hero’s son. Though the emotionally unavailable, hurting boy is, again, no fresh archetype, Scott is still softened by this reality, and through his storyline with Roy’s children.

When Roy first sends Scott to his ex-wife Gina’s house to pick up the kids for school, Gina asks Scott if he is a “weirdo.” When he replies with a characteristically cheeky, “Oh the weirdest. Nobody’s weirder than me,” she counters as we do in our own minds, “A weirdo wouldn’t say that. A weirdo would deny it.” We know better than to level with Scott’s projected self, and are justified in our suspicions of his softness as he takes the hands of the two kids and walks them to school. We find out later from a conversation between the boy, Howard, and Roy that Scott also drew Howard a sketch of the superhero he invented, “Ice Man.” It is this tender act and the palpable talent Roy sees in the sketch that convinces him to let Scott practice his tattooing skills on Roy’s untattooed back — alien doodles, family portraits and all. And when Margie later sees the fruits of his labor during a warm reunion, we see her most delicate tears.

The second act has a few stragglers — including a misfit pharmacy robbery — but its decadence lies with the montage of Scott and the local firefighters, who take him in when he realizes he has nowhere else to go. They sing pitchy karaoke, joke about the millennial work ethic (or, more precisely, the lack thereof) and play pranks on each other. Meanwhile, Roy and Scott work on burying the hatchet. While this relationship comes as a surprise, it suits the generally rosy conclusion of the film — one I would not expect from Davidson but see coming from Apatow. And it is crucial for Scott, who has harbored resentment against his father for refusing to choose between the superhero story and the family story. As he watches Roy and the other men race up clanking ladders into a burning building in classic firefighter fashion, his face lights up, and we suddenly know — simply but surely — that he has forgiven Stan. (Also, he can’t help but respect his father in that twisted but endearing way when he finds out about Stan’s coke days.)

In the end, he clumsily apologizes to his mother for wreaking such havoc as her kid and tells the girl — again, a genius Powley — he loves her. And though it is a tad saccharine, we are grateful after three or so pseudo-endings that the film has finally concluded. I fell in love with Davidson when Scott says to Marge, “I’ll try and get it together. It’s just hard. I think it will always be hard.” Though it is Scott’s dialogue, it is Davidson’s voice. It may be merely that I’ve come to expect so little emotional vulnerability from straight men — on the screen and otherwise — but these lines struck a chord.

These days are hard, but “The King of Staten Island” made this particular Wednesday a little easier.

Contact Malia Mendez at mjm2000 ‘at’ stanford.edu.