It’s old news that artificial intelligence is transforming the world, with Stanford at the forefront of this trend. Numerous major research breakthroughs in artificial intelligence have grown out of the University, and many former and current faculty members are pioneers of the field.

As part of the Stanford in the 2010s series, which explores how the University has (or hasn’t) changed in the past decade, The Daily’s Data Team analyzed Explore Courses data to understand how computer science courses pertaining to artificial intelligence have changed.

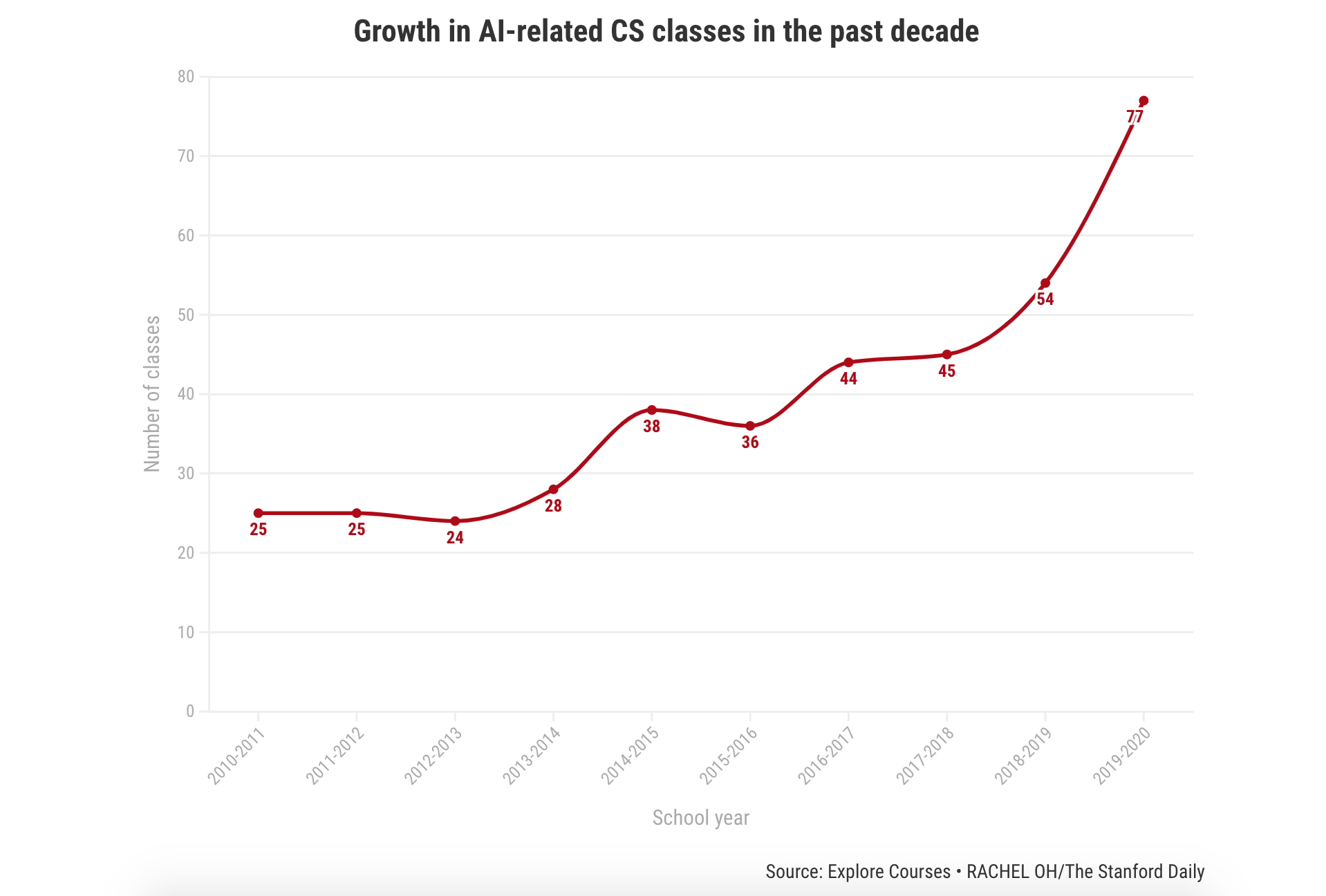

Both artificial intelligence classes in the computer science department, as well as the number of enrolled students, increased in the past 10 years. Many classes that were top choices at the start of the decade also remained popular until 2020, although their sizes grew significantly.

Breaking down the rise

The total number of computer science classes related to artificial intelligence more than tripled in the past decade from 25 classes to 77 classes. After the initial jump in 2014, the number of classes has grown steadily since 2015. The steepest increase came in the most recent academic years, between 2018 and 2020. (See the methodology section for a detailed description on how AI-related classes were defined.)

Classes related to machine learning consistently had the highest count throughout the past 10 years. Machine learning also saw a relatively constant increase in the number of classes offered, from fewer than 10 to nearly 40. This is likely because the other categories like natural language processing or deep learning fall under the broader category of machine learning.

Classes related to deep learning were first offered in 2014, but the number of classes quickly surpassed those of natural language processing and computer vision courses. Natural language processing classes have also been increasing more rapidly since 2016, while computer vision courses have been growing at a slower pace.

The trends on course offerings show that there are more artificial intelligence classes available in general, as well as a larger variety of classes across subtopics of AI.

“There is more flexibility and there’s more availability [of courses],” said Mehran Sahami ’92 M.S. ’93 Ph.D. ’99, a professor and the associate chair for education in the computer science department.

A major change that contributes to this flexibility was the introduction of the track system in 2008. The track system offers a flexible curriculum that ensures students take core foundational classes along with additional classes that align better with their specific interests, such as artificial intelligence, biocomputation and a few others.

“People have lots of different options for what they want to emphasize,” Sahami said.

Within the artificial intelligence track, machine learning is considered an essential area for Stanford students to learn.

“Machine learning was one of the areas in AI that we thought was kind of most important for everyone to see, which is why that area is required for everyone,” Sahami said. “Through a class like CS 109 that provides an introduction to machine learning, everyone in the CS major will be guaranteed to see at least that level of stuff.”

Winners take all: Many popular courses grow further in size

Despite the large increase in the course offerings, the courses with the highest enrollments — many of which emphasize machine learning — remained relatively constant in their rankings. But the sizes of many of those classes multiplied.

CS 229: Machine Learning, which was the most-taken course throughout most of the past 10 years, grew from 318 students in 2010-11 to 869 in 2019-20. Similarly, CS 221: Artificial Intelligence: Principles and Techniques and CS 109: Introduction to Probability for Computer Scientists increased dramatically in class sizes, from fewer than 300 students to 700 or more students.

A driving factor of the increase was the explosive growth in student demand.

“It’s clearly all student demand-driven, which is just reflecting the huge breakthroughs that have been made in AI recently and the huge enthusiasm among students to learn this,” said Christopher Manning Ph.D. ’94, a professor in the computer science and linguistics departments and the director of the Stanford Artificial Intelligence Lab (SAIL).

Part of the increase in demand comes from the rise in the number of students studying computer science — and in particular, specializing in artificial intelligence.

“We’ve certainly seen student interest grow tremendously in the last 10 years in computer science as a major,” Sahami said. He estimated that the major has grown by about 300 to 400 percent since 2007, making it the most popular undergraduate major at Stanford.

Among the multiple tracks that exist within the computer science department, the artificial intelligence track is the largest.

“We’ve seen the size of the AI track increase over time, and it’s the most popular track now, similarly with the master’s program,” Sahami said.

In addition, students outside the computer science department increasingly took artificial intelligence classes in the department.

“There are starting to be kind of increasing numbers of Ph.D. students from all sorts of departments who want skills in machine learning,” Manning said, such as students studying business, education or law.

On the other hand, CS 223A: Introduction to Robotics, which used to be the fifth most popular class in 2010-11, has fallen in popularity. While there were 92 students enrolled in 2010-11, there were only 64 students enrolled in 2019-20.

Enrollment in CS 224N (formerly Natural Language Processing and now Natural Language Processing with Deep Learning) and CS 231N: Convolutional Neural Networks for Visual Recognition’ hit a peak in 2016-17, then dropped slightly, although the courses still remain relatively popular. CS 224N changed its name in the year it hit the peak.

“[Around mid-2010s] we started offering deep learning for NLP and [computer] vision classes. And then it was suddenly that NLP and [computer] vision were teaching classes with 500, 600 students,” Manning said.

New popular classes have also emerged, such as CS 230: Deep Learning. The course first appeared in the 2017-18 academic year and has consistently had more than 800 students since its inception.

Many of the artificial intelligence courses that are now popular among undergraduate students were “originally primarily intended as graduate level AI classes,” according to Manning.

A consistently popular class, CS 229, was also originally intended for Ph.D. students who were going to do machine learning research. “That sort of reflected the nature of the class until a few years ago, where it was mainly writing on the blackboard like an old-fashioned math class,” Manning said.

Explaining the rise: Student demand and industry-wide changes

Students in the artificial intelligence track shared the various reasons they decided to pursue such a path. Nik Marda ’21, a senior and a co-term student in computer science, said he always had a dual interest in politics and math, which developed into a passion for shaping better artificial intelligence policies.

Manan Shah ’21, also a senior and co-term in computer science, said he participated in multiple research competitions using deep neural networks for applications in medicine and health. “I always thought there’s a lot of upside in using AI for meaningful things,” Shah said.

More hiring in the faculty enabled a broader range of classes to be offered and helped “meet more student demand,” according to Sahami. The growth in student interest and in faculty members is “an indication of the growing importance of this area of computer science,” Sahami said.

The 2010s were also when “more started to happen,” according to Manning. “I think it’s basically that AI started succeeding — that there started to be all sorts of uses of machine learning in the world.”

“In the 2000s decade, things really changed for the first time. So, there was an enormous emphasis on probabilistic models in AI, and probability was seen as the way to model uncertain thinking in an uncertain world,” Manning added. “Then this period started to see the rise of machine learning.”

Manning also mentioned that “starting around 2010, there started to be another sea change” — artificial neural network approaches and deep learning approaches. “That’s now sort of swept everything including most coursework at Stanford, and really, the vast majority of researchers now doing things with neural networks for artificial intelligence,” Manning said.

Students studying artificial intelligence also recognize how intertwined Stanford’s courses and the professional world are. “For certain AI classes, the class lectures for those are actually cited in papers referenced everywhere; [they are] like ‘the’ documents for learning a certain subject,” Marda said.

“Stanford’s AI classes don’t exist in a bubble,” Marda added. “They are fueled in part by industry; they are relevant to industry; they are used by other people. And I think all of that affects the growth that we’ve seen.”

Methodology

The classes counted in the first and third graphs are computer science department courses where the last digits of the class codes are 20 to 39, as the Explore Degrees page for computer science defines those as primarily “artificial intelligence” classes. To obtain a more comprehensive set of AI courses, classes that contained at least one of the five terms artificial intelligence (AI), machine learning, deep learning, natural language processing (NLP) or computer vision in the course title or course description were also included.

The second graph was solely made based on classes that contained one of the five aforementioned terms in the title or description. Note that some classes in the graph may have been double-counted if they contained multiple relevant keywords in their titles or descriptions.

The data for all three graphs come from scraped Explore Courses data. Discussion sections, independent studies, labs, research classes and summer classes were excluded.

Contact Rachel Oh at racheloh ‘at’ stanford.edu and Peter Maldonado at phm ‘at’ stanford.edu.