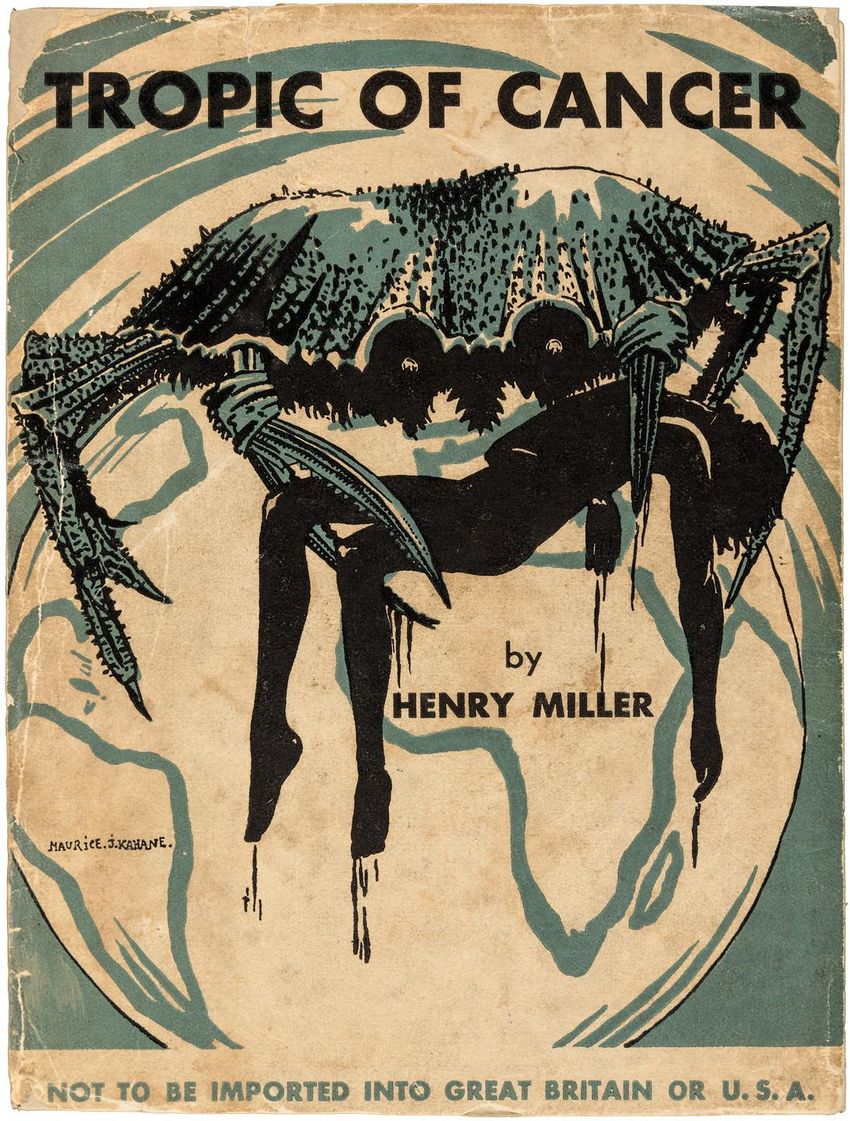

Here’s a quaint historical fact: Henry Miller’s novel “Tropic of Cancer” was banned as obscene in America for 27 years after its first publication in 1934. All over the West, authorities seized and destroyed hundreds of imported copies. When the book finally hit shelves in the U.S., dozens of concerned citizens filed lawsuits against the shopkeepers who stocked it. While most lawsuits narrowly lost, the dissenting opinions suggest that many Americans continued to take issue with the novel’s content. Consider this assertion from the pen of Judge Michael Musmanno: “[“Tropic of Cancer”] is a cesspool, an open sewer, a pit of putrefaction, a slimy gathering of all that is rotten in the debris of human depravity.”

Contemporary readers must first marvel at Musmanno’s poetic capacity. Are all judicial opinions rendered in such vivid language? We then rush to our bookshelves. The prospect of this “slimy gathering… of human depravity” has intrigued us. There must be a copy lying around somewhere. We search through a mountain of neglected books and find “Tropic of Cancer” buried at the bottom. Anaïs Nin, who edited the novel, claims that it will “restore our appetite for the fundamental realities.” We have no idea what this statement means, but it sounds nice. Norman Mailer calls it “one of the great novels of our century.” Karl Shapiro, writing in 1960, describes Miller as “the greatest living author.” We are on the edge of our seats, champing at the bit to begin reading.

The sex scenes were said to be phenomenally stimulating in their day. One likes to imagine that contraband copies of “Tropic of Cancer” were passed around by frustrated college students and safeguarded in nightstand drawers. Vulgarities and what elderly schoolteachers might call “bawdy language” abound. Miller’s prose is a dense forest in which the smells of rotting carcasses and fragrant plants compete for primacy. His eponymous narrator, an American writer adrift in Paris, likens himself to vermin crawling in the city’s gutters. The supporting characters — friends, lovers, adversaries and strangers — are each as self-serving and wretched as the next. Those interested in “the moral” of the story may search at their own peril. The rest of us happily make do with the misery and descriptions of the Seine.

Of course, it should be said that nothing in the book shocks us. Not the graphic odes to women, not the ubiquitous profanity and especially not the abundant descriptions of sex. We imagine the author slouched over a typewriter in a dirty room in Paris, wracking his brain for lewd epithets and giggling at the thought of unsuspecting readers’ reactions. Poor Henry Miller! A frisson of pity courses up our spines. Who can blame him for his inability to anticipate changing social mores? Who can fault him for failing to anticipate the sexual revolution, spring break at Daytona Beach, wet T-shirt contests, “Grand Theft Auto: Liberty City Stories” and free, unlimited hardcore pornography available at the click of a button?

The response of a Gen Z reader to “Tropic of Cancer” would seem to illuminate a subtle consequence of our hypersexualized modern culture. Namely, those who spent their formative years marinating in Internet pornography (and its various cultural corollaries) have become insensitive to artistic representations of the erotic experience. We’ve lost our taste for things left unsaid or unseen. We’ve sacrificed our imaginative capacities at the altar of instant gratification. Critics of our “pornified” modern culture tend to ignore these effects. Much has been written about the addictive nature of online pornography; about its deep connections to trafficking and about its destructive effects on intimate relationships. After all, we are fast-paced moderns with little patience for niceties about poor taste…

The skeptical reader bristles. Haven’t young adults always gorged themselves on porn? What about “Playboy,” erotic literature and grainy ‘adult videos’ from the ’70s? Where’s the harm in all of that? Upon closer examination, we find that none of this content bears much resemblance to the current pornographic paradigms. Internet porn favors specific, mechanized choreographies of intercourse. Unlike the hourslong films of the ’70s and ’80s, today’s porn eschews narrative progression. It subsumes all sensual and erotic grammars within the matrix of on-demand pleasure.

In fact, we might say that Internet porn is the sexual analogue of one-click Amazon purchases, 30 second news clips and instantly updated personal feeds. The long-term consequences of these technologies remain unclear. Imagine the world in which everyone has grown up on PornHub and TikTok. What kind of books will sell? What kind of films will be watched? Will there be an appetite for metaphor and innuendo? How will we spend our creative energies?

In the grand drama of Progress, young people have always played the role of unwitting guinea pigs. Maybe in 30 years we’ll take stock of the damage done to our sensibilities and swing the pendulum backwards. Self-abnegation will come into fashion. Personal development books will fly off the shelves. Celebrity influencers will sell us their favorite chastity belts. Never mind that for now. We want life at high speed. Next-day delivery. Instant download. Satisfaction guaranteed. Don’t pity Henry Miller — “Tropic of Cancer” never stood a chance.

Contact Sanjana Friedman at sfriedm ‘at’ stanford.edu.