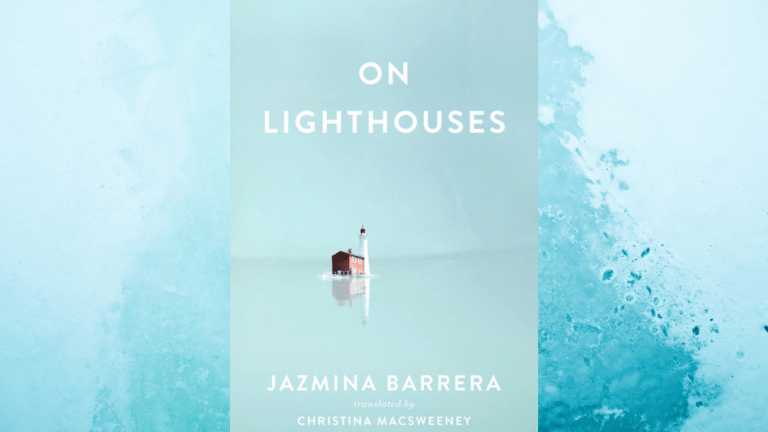

The material design of the new English translation of Jazmina Barrera’s “On Lighthouses,” published in May of this year, is oddly prescient of our current state. Soft, light blue soaks the cover and almost engulfs the tiny, red and white lighthouse at its center, marooned amid the uniform color. Here, already, Barrera announces the raison d’être of her little text: to investigate the overwhelming loneliness of the lighthouse, and, by extension, ourselves.

And when else would we most relate to this proclamation, if not now? Now is a time when each of us is more or less marooned on our isles of isolation, stuck like stoic sentinels in our own lighthouses, making signals to people far away through each of our light screens, signals that say, desperately, someone is here — and all this amid that uniform blue, the days passing us by until they are no longer units to be differentiated, but rather a single entity like the sky or the sea, swallowing us in its immense infinity, silence and solitude.

Yet, we know — from Barrera as well as numerous other representations of lighthouses (what first comes to mind is Robert Eggers’s 2019 movie “The Lighthouse”) — that one may be driven mad by the sheer isolation that takes place within a lighthouse. Indeed, it does seem that “the absence of communication is one of the greatest dangers for a gregarious species like Homo sapiens.” I wonder if we all have gone a little mad these last months simply because we are so alone. Barrera quotes a lighthouse keeper: “‘On these islands,’ he says, ‘loneliness is a problem. It turns you into a philosopher.’”

***

The cover is what first drew me — a materialist, I admit — to pick up “On Lighthouses” from my local bookstore. I had been eyeing it as it sat in my virtual shopping carts for a few weeks, but could never commit to the final act of pressing “Purchase.” Somehow, I have always hesitated in the face of virtual transactions, in buying products that I cannot feel with my hands.

But the cover was not the only factor in my purchasing decision. Ever since my first encounter with Virginia Woolf’s “To the Lighthouse,” I, like Barrera, have romanticized the idea of the lighthouse, pariah of nature and society both. The structure of the lighthouse carries with it many symbolisms and meanings, from its purpose as a guide to lost ships, through its separation from human contact, to its liminal positioning on the coastline. It is at once a beacon of communication and the antithesis of it. Anchored yet abstract. Close and far.

Barrera makes diligent and revelatory use of these symbolic resonances in “On Lighthouses,” which is part autobiography, part literary and regional history, part rumination. The book is divided into sections titled after different lighthouses that Barrera visits. Each story of her journey to that particular lighthouse (emphasis on the journey to — very Woolfian) is used as a thread throughout that section, as she weaves together various literary and artistic references, fragments from histories of lighthouses and associated historical figures, and extended contemplations on certain images such as bats, ships and fireflies. Larger themes are interwoven throughout the whole tapestry of the work, themes which Barrera comes back to over and over again: the process of collection, loneliness and madness, the past resisting the present, nostalgia for something unfamiliar, and so on.

Indeed, the idea of collection and collecting is central to “On Lighthouses.” Barrera begins the book discussing how she began to “collect” lighthouses, not only by visiting them but by researching the “history … and stories surrounding them”: “And it was like falling in love,” she says (a line oddly similar to one on the opening page of Maggie Nelson’s “Bluets” — another book about collecting something impossible to collect — “I fell in love with a color”). Collection gives Barrera direction. It gives her a sense of purpose in a world that so often lacks it, even if that purpose is a superficial one.

Collection underlies the very form of “On Lighthouses,” too. At first glance, this book appears fragmented, with Barrera jumping from anecdote to historical background to source material to internal thought. Often, these pieces are simply placed on the page, separate entities left to speak for themselves. This fragmentation is the nature of a collection: Each element, though thematically related to the rest, is still its own. Yet when you grow a collection, those thematic resonances accumulate, and the fragments begin to speak together in harmony, and — who knows? — maybe even in melody. Just by existing together, they tell a story. As Barrera says, collecting is “a repetition that produces new meaning with each addition.” Through this mode of narrative, “On Lighthouses” is expansive in its reach, and poignantly touches on many aspects of the human condition despite its relatively shorter length and arguably limited subject matter.

***

But though it reaches many people, places and time periods, “On Lighthouses” surprisingly ends with a series of short diary entries, à la James Joyce’s “A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man.” It is apt to make this comparison because Barrera herself is clearly influenced by literary modernism, evident in her allusions but also in her very manner of thinking. The main character of “A Portrait” is Stephen Dedalus, a young artist coming of age in an artistically stifled Dublin; he, too, like a lighthouse, is a radiant outcast. At the end of the novel, the narration suddenly shifts to the perspective of Stephen’s diary as he gets ready to move to Paris. The break from third- to first-person signals a turning both outward and inward: Stephen preparing for his journey into the world, but also Stephen reflecting on himself, illuminating himself.

Barrera, too, ends on a journey. After a long exegesis on the lighthouse in all its representations and abstractions, in the final section of the book she comes upon the last and most substantial lighthouse to explore: herself. Just as a collection is forever incomplete, the journey of understanding the self is infinite, and does not end with the ending of a book, or after writing one. It is a constant movement forward, one from which “there is no way to return.” But it is also cyclical, never-ending, like the relighting of the lamp each night through the centuries, just in case a ship is returning home.

If the absence of communication seems to be such an immediate danger to human sanity, I wonder, again, what will happen once we all emerge from our own little lighthouses, our journeys of solitude and introspection. In a particularly evocative anecdote, Barrera writes about a close friend who spent some time in a silent retreat:

“For the first time, she seemed different. When, some days before, I’d asked her if it had been very hard to spend ten days in silence at the retreat, she’d said no, it had been the easiest thing in the world. The difficulty had been speaking again; after that experience, almost all words seemed unnecessary, a waste of time … and that pleased but also saddened me. We were still alone, just as before, but Ximena’s aloneness was more luminous.”

Will we emerge from our towers like Ximena, with a “luminous aloneness” that comes with self-discovery? I am sure some will, having realized a sort of redundancy to language, to certain forms of communication. Certainly I have realized things about myself in this time, and about my social and communicative priorities. But I think many of us will relate to Barrera herself, too, who then “felt that Ximena had understood something I hadn’t yet managed to grasp.” Self-revelation is a process that does not end. We still continue relighting our lamps, day after day, sending out beams of white into the fog. Not always just to signal to others that we are here. Sometimes just to remind ourselves.

Contact Lily Nilipour at lilynil ‘at’ stanford.edu.